The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Beethoven Reviews

Mozart Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

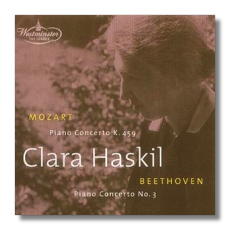

Clara Haskil

Plays Mozart & Beethoven

- Wolfgang Mozart: Piano Concerto #19 in F Major, K. 459

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto #3 in C minor, Op. 37

Clara Haskil, piano

Winterthur Symphony Orchestra/Henry Swoboda

Westminster 471264-2 ADD monaural 64:28

In one frequently reproduced photograph of Clara Haskil, she is holding a comfortable yet alert cat in her arms. If Haskil did not have, cat-like, nine lives, she had at least several. Born in Bucharest in 1895, she quickly showed aptitude for the piano. She was sent to study in Paris with Alfred Cortot, who disparagingly pronounced her "a character." By the early 1910s, she had become a virtuoso pianist. Then scoliosis immobilized her in a plaster cast for more than four years. Her muscles atrophied. It was 1920 before she could return to concertizing, and by then, athletic displays were no longer of interest to her, and no longer possible. Now she was haunted – and would be until the end of her life – by stage-fright and intense self-criticism, so much so that she would cancel her participation in concerts with little warning. In 1942, she underwent an operation for a brain tumor. A Jew and residing in France during these years, she lived a precarious existence. It wasn't until after World War Two that Clara Haskil arrived as an internationally known concert pianist. By the time she could purchase her own grand piano, she was 57! By then, she was called "a saint of the piano." One German critic wrote, "She was sent to Earth to play Mozart." Haskil died in 1960 after falling down the stairs in a Belgian railway station. She was 65, but in some ways, her career had barely begun.

This CD reissue contains some of Haskil's earliest commercial recordings; they come from September and October 1950. The conductor, Henry Swoboda, was one of the founders of Westminster Records, which had been born just a year earlier. Haskil was a good catch for the young record label, and these recordings spoke to listeners of that era. They still have something to say. Haskil plays the two concertos intimately but not reticently. Though not note-perfect, her technique grants her beauteous legato playing and a pearly tone. Runs and arpeggios are distinct and smooth. There is no thundering, even in the Beethoven. In fact, the dynamic range in both concertos is fairly narrow (perhaps also a by-product of the engineering, which is a little clouded), but it is infinitely and tellingly varied within that range. No fuss, no showmanship, just a luminous sincerity – that was Clara Haskil.

The Winterthur Symphony Orchestra (Switzerland) is no great shakes, but Swoboda is at one with Haskil's self-effacing interpretation. Later, Haskil re-recorded these concertos with conductors Ferenc Fricsay and Igor Markevitch, respectively. Those versions might be worth hunting down for the stronger orchestral accompaniments, but Haskil/Swoboda is here for the taking, and it would be a shame to miss it.

More viscerally impressive recordings of these two concertos would be easy to find, but it would be hard to find many contenders for Haskil's quietly musical integrity. Her pianism has a place in anyone's collection.

Copyright © 2002, Raymond Tuttle