The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Donizetti Reviews

Offenbach Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

The Westminster Legacy

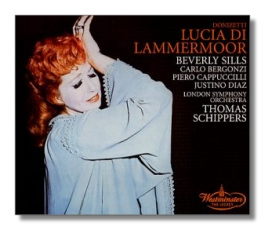

Gaetano Donizetti

Lucia di Lammermoor

- Beverly Sills (Lucia)

- Carlo Bergonzi (Edgardo)

- Piero Cappuccilli (Enrico)

- Justino Diaz (Raimondo)

- Adolf Dallapozza (Arturo)

- Patricia Kern (Alisa)

- Keith Erwen (Normanno)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus

London Symphony Orchestra/Thomas Schippers

Deutsche Grammophon Westminster 471250-2 ADD 2CDs: 70:03, 76:50

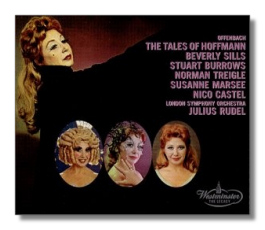

Jacques Offenbach

Les Contes d'Hoffmann

- Beverly Sills (Olympia/Giulietta/Antonia/Stella)

- Stuart Burrows (Hoffmann)

- Norman Treigle (Lindorf/Coppélius/Dapertutto/Miracle)

- Susanne Marsee (Nicklausse/La Muse)

- Nico Castel (Andrès/Spalanzani/Pitichinaccio/Frantz)

- Robert Lloyd (Crespel)

- Patricia Kern (Voice of Antonia's mother)

John Alldis Choir

London Symphony Orchestra/Julius Rudel

Deutsche Grammophon Westminster 471247-2 ADD 2CDs: 72:06, 77:21

These two sets have been a treasured part of my LP collection for many years, as they have not found their way to CD until now. (I suspect they were lost in the limbo of licensing agreements.) The focus, of course, is American diva Beverly Sills, but there is a great deal more to these recordings than merely "Bubbles."

The Lucia was recorded in London's EMI studios in August 1970. Several non-vocal features make this performance, well sung as it is, particularly recommendable. For one, conductor Schippers elected to restore music – sometimes large chunks of it – that often used to be deleted both on stage and on disc. Few recordings are as complete as this one. Granted, not all of the restored material is of crucial importance, but even a few bars here and there make this "grand" opera even grander. The most lengthy restoration is the so-called "Wolf's Crag" scene at the beginning of Part Two. In this scene, Edgardo and Enrico, both hell-bent on revenge, breathe fire at each other, and Donizetti responds with an appropriately militant duet for tenor and baritone. Another interesting restoration is the Lucia-Raimondo duet in Part One, in which the Ashton family chaplain counsels Lucia to obey her brother and marry Arturo. When this scene is omitted, it makes Lucia's apparent desertion of Edgardo look silly and under-motivated. Even the restoration of a few words, however, can add much to the understanding of a character. Usually, Lucia's "Mad Scene" ends the opera's penultimate scene, but what Donizetti wrote was an (admittedly anticlimactic) dialogue for Raimondo and Normanno in which the chaplain hypocritically blames Normanno for the tragedy just witnessed. Musically, this dialogue is nothing much, but dramatically, it twists the knife.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the only recording to use the glass harmonica (here, played by Bruno Hoffmann) in the "Mad Scene." Donizetti apparently thought its pallid and unearthly tones would be perfect to accompany Lucia's pretty rantings, but when he realized that most opera houses had access neither to the instrument (a complicated cousin of the wetted rim of a wine glass) nor to qualified players, he replaced it with a flute. Its presence on this recording is of both artistic and historical value.

In the title role, Beverly Sills gives everything she's got. For some, her voice is an acquired taste: while brilliant, the sound is often not exactly beautiful, and some odd sounds come out of her throat. (A friend once remarked, "She doesn't just trill a note, she trills the whole chord!") Curiously, her sound, while it projects, lacks weight – it's almost as if she is hollow inside. The high notes and the agility are dazzling, however, and dramatically, she is perceptive and lacking neither in pathos nor in vulnerability. In short, Sills's Lucia is a classic portrayal, but it's not for everyone. Bergonzi, on the other hand, is beyond criticism as Edgardo. Although he was fresher-voiced in his RCA recording with Anna Moffo, he is everything one could desire in this role: proud, heroic, ardent, impulsive, self-pitying, and yes, sexy… and his perfect tenor voice just does not quit. The "Tomb Scene," no anticlimax, brings this Lucia to a thrilling conclusion. Cappuccilli is a domineering Enrico, but no mere bad guy, as his forceful but essentially melodic singing suggests. Less admirable are Justino Diaz's woolly Raimondo and Adolf Dallapozza's strained Arturo. Schippers, sometimes guilty of pushing too hard on his other recordings of Italian opera, does right by Donizetti here. The engineering is not top-of-the-line; the sound can be harsh, and it lacks fullness. It doesn't ruin the performance, however.

The Tales of Hoffmann, recorded in the same studios almost exactly two years later, tops the Lucia. Again, textual issues had to be worked through; Hoffmann, because the composer passed away before he had the chance to revise it – as he surely would have – is one of the most open-ended operas in the basic repertoire. This version also contains passages missing in many other recordings, including both verses of Lindorf's song in the Prologue, and the Muse's (Nicklausse's) framing of the action in the Prologue and the Epilogue. Rudel places the great septet in the Giulietta scene, which follows Olympia and precedes Antonia.

Sills succeeds in the tour de force of singing all three soprano roles (four, if you count the enigmatic Stella). She sounds most comfortable with Antonia (the trio with Dr. Miracle and the voice of her mother raises goosebumps), but she clearly enjoys Olympia's coloratura, and also her vamp-like touches of evil for Giulietta. Though it may be heresy to say so, this performance is a bigger achievement for her than her Lucia is. Burrows, an under-recorded tenor, superb in Mozart and in several of the French roles, is perfect in the title role. His voice has the requisite lightness and flexibility, yet the brooding timbre of his lower range suits the poet to a tee. When he and Sills get together, man, that's opera.

Treigle, another under-recorded singer, gives a wonderfully old-school Mephistophelean performance in the nemesis roles. This is singing in the vein of Leonard Warren or Lawrence Tibbett. His hamminess is delightful – not at all annoying – and while one can easily find a baritone with a deeper bag of vocal abilities than Treigle, it is hard to find one who sings "Scintille, diamant" with more intensity, or who brings more zest to his characterizations.

Marsee's Nicklausse makes one wonder why she is not better known. She makes the most of her chances, sparkling in her little song about the doll with enamel eyes, and really turning on the sex appeal for her spoken monologues as the Muse. Nico Castel brings good comic sense to Frantz's couplets in the Antonia scene, and excels in his other three roles. Robert Lloyd is strong as Antonia's father, and Patricia Kerns brings the necessity authority to her brief stint as the ghostly voice of Antonia's mother.

The entire performance is moved along by the decidedly large-scaled conducting of Julius Rudel, a favorite colleague of Sills's. Cluytens, in either stereo or mono, is perhaps more authentic, but he certainly has more variable casts. Nevertheless, Rudel understands how Hoffmann plays on the stage, and he turns that knowledge into a larger-than-life performance. Where others may charm and beguile, he and his international cast of singers astonish and frighten.

The sound on this recording, while generously resonant, is quite a bit better than it is on the Lucia. I am guessing that microphone placement saved the day.

I'm prepared to go out on a limb and call the Rudel/Sills Hoffmann the best on CD. The Schippers/Sills Lucia is also recommendable, but one might also consider the strong competition offered by Bonynge/Sutherland.

Copyright © 2002, Raymond Tuttle