The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

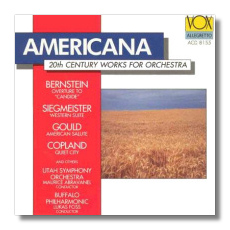

Americana

20th-Century Works for Orchestra

- Leonard Bernstein: Overture to Candide

- Elie Siegmeister: Western Suite

- Morton Gould: American Salute

- Leroy Robertson: Punch and Judy Overture

- Vaclav Nelhybel: Étude Symphonique

- Carl Sprague Ruggles: Men and Mountains *

- Charles Ives: From the Steeples and Mountains *

- Aaron Copland: Quiet City *

Utah Symphony Orchestra/Maurice Abravanel

* Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra/Lukas Foss

Vox Allegretto ACD 8155

Collectors of American music remember with gratitude the Columbia American Music Project and Black Composers series, CRI, and Louisville First Editions, as well as a host of smaller labels like Composers Recordings and Crystal. However, other labels would also sporadically test the waters. In the 70s, Vox/Turnabout came out with its series "The Contemporary Composer in America," as well as with wonderful boxed sets of American string quartets and choral music. The works on this CD give a fairly good idea of Vox performances and repertoire in this area.

Most collections come off as a mixed bag: some items hit, others don't. Leroy Robertson's "Punch and Judy Overture," despite an interesting opening, settles down into a pale, genteel ghost of Pétrouchka. Utah composer Robertson is probably best known for his Oratorio from the Book of Mormon, also recorded by Abravanel. It exhibits the same musical gentility, occasionally interrupted by flashes of lightning.

Bernstein's "Overture to Candide" has become an American classic, surely one of Bernstein's best scores (as is the entire show) and, with Barber's "Overture to The School for Scandal," the best comic overtures since Mozart. Bernstein was usually his own most persuasive advocate, and Abravanel certainly does nothing to surpass Bernstein's readings. The Utah strings articulate more precisely than the New York Phil's, but the sound has much less weight. Abravanel's account proceeds just a shade too carefully, without Bernstein's swagger. Furthermore, the Utah trumpets consistently miss a note in one of the themes – bad edition?

Elie Siegmeister's music has largely been forgotten by recording companies – a bit of a shame, really, because everything I've heard (and that's not much) has shown a very interesting musical mind. The Western Suite and the Ozark Set come as close as anything to a musical "hit," the former taken up by Toscanini. Siegmeister's brand of Americana comes closer to Harris's than to Copland's or Thomson's. Harris also suffers from an eclipse of practical interest in his work. Perhaps when he comes back, Siegmeister will as well. Copland, in print, paid Siegmeister's music the left-handed compliment of "crude effectiveness." Certainly some moments in the Western Suite don't come off, but there's also a lot of poetry in it, particularly in its quieter moments, and it's not yet another ripoff of Billy the Kid or Rodeo. It makes me want to hear Siegmeister's symphonies.

Gould's music – to judge from the current Schwann catalogue – seems to have made a comeback, and his American Salute has become something of a CD-demo classic. Abravanel presents an energetic, straightforward reading, but the thin recorded sound works against him.

The real find of this disc, however, and its raison d'etre as far as I'm concerned is Vaclav Nelhybel's Étude Symphonique. This name will strike a bell with very few, and those few probably band nerds. Born in Czechoslovakia, Nehybel fled to Switzerland in 1948 and finally settled in the U.S. in 1957. His music belongs to the Stravinsky-Bartók wing of European modernism but sounds no more like these composers than does Martinů's. According to John Doucet, a major enthusiast, there's a whole garage-full of unpublished scores, many in large genres. The Étude Symphonique is not only a piece for virtuoso players, but an exemplar of bravura composing. The whole thing grows out of a three-note idea, almost always sounding but never crossing the line to monotony. To some extent, a genius orchestrator provides various colors, but the real work comes in the variations Nelhybel works on those three notes and in the new, bold ideas he can get the motive to summon forth. I don't want to mislead anyone when I talk of the composer's orchestration skill: the colors come from the grim, rather than the brilliant or sensual side of the palette. However, they fit the music perfectly. The work attracts me not only through its intellectual development, but also through its absolutely electric rhythms. Abravanel leads a driving, committed performance. Again, the performance lacks a weight of sound the music can well handle, and I'd love to hear Chicago or Cleveland tackle this, or anything in that garage. No kidding, folks, this is a big voice.

As far as I know, Foss leads the only available recorded account of Carl Ruggle's epic Men and Mountains. Ruggles didn't write much, merely masterpieces. Many have compared his work to Ives, and Ives, seldom all that interested in other living composers, indeed championed Ruggles's music. Nevertheless, I find little similarity in the two composers, other than they both hailed from New England. Ruggles moves more purposefully and meanders less than Ives. His surfaces are clearer. Foss and the Buffalo Philharmonic get through the work, but this music needs heroic, thrilling sound. Those who remember Michael Tilson Thomas's reading of Sun-Treader with the Boston Symphony might be disappointed here.

Foss made Ives' From the Steeples and the Mountains almost his party piece. He's conducted it everywhere. I attended a Cleveland Orchestra concert, score in hand, early in Foss's conducting acquaintance with the work, and saw him throw the wrong cue at least five times to the principal trumpet, who steadfastly refused to come in until the proper moment. Like many Ives works, this one seeks to reconstruct one of the composer's "natural" musical epiphanies – the simultaneous clangor of bells from different churches on Sunday. I can't vouch for my memory, but I believe Thoreau describes something similar – walking through the mountains on a Sunday and suddenly wallopped with the sound of church bells from different, neighboring towns. A lovely, rugged work, not all too often played and recorded.

Foss turns in an ok account of Copland's Quiet City, but the sound again works against the performance. Copland, despite his neoclassical togs, is a big-city Romantic in disguise. A piece that depicts a guy playing a trumpet on the rooftop at night you can't really call cool and distant. This performance is way too matter-of-fact. It doesn't come close to Bernstein's reading or the composer's own, and the Buffalo sound is too thin, besides.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz