The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

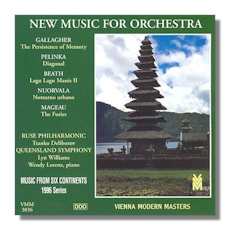

Music from Six Continents - 1996 Series

New Music for Orchestra

- Jack Gallagher: The Persistence of Memory ** (1995) 19:31

- Werner Pelinka: Diagonal, Op. 27 (1994) 6:04

- Betty Beath: Lagu Lagu Manis II (1994) 7:23

- Juhani Nuorvala: Notturno urbano (1996) 9:07

- Mary Mageau: The Furies * (1995) 19:50

* Wendy Lorenz, piano

** Bogdana Peneva, cello

Ruse Philharmonic Orchestra, Bulgaria/Tsanko Delibozov

* Queensland Symphony Orchestra/Lyn Williams

Vienna Modern Masters VMM3036

This is an appealing collection of orchestral pieces written within a year of one another, each accompanied by notes commenting on the composers' intentions. Except for Mageau's, the notes are by the composers.

Jack Gallagher's Persistence of Memory was originally for wind ensemble and in its present form is dedicated to the Cleveland Chamber Symphony, which gave its first performances. It is an elegy, and as in the case of Gallagher's 1991 Symphony in One Movement: Threnody (on Naxos 8.559652), it is associated with a personal loss, in this case his friend and colleague Brian Israel, who taught composition and music theory at Syracuse until he died at 35. Beginning relatively softly but with drum taps, the music brightens temporarily before the pace picks up and drums sound an obsessive figure, against a piano. Dynamics increase, eventually coming to a loud, angry, dissonant, Sacre-like passage with winds and percussion. After the outburst, there is sudden quiet and a quiet four-minute solo cello sounds a leisurely lament. High woodwind sounds signal a change of mood. Finally we are let down gently and beautifully to a peaceful end, punctuated softly with bells.

Throughout Gallagher's work, the scoring is effectively transparent. Besides a wide selection of percussion instruments, including piano, used with a full range of dynamics from very soft to quite loud, harp, bass clarinet, horn and high woodwinds are used effectively, and a brief trumpet solo is significant. This is a fine piece and a fitting companion to his symphony.

Werner Pelinka tells us that his Diagonal, dedicated to his wife, is an interpretation of Goethe's notion of the attraction of the "eternal feminine." The loveliness of the feminine part of the composition does honor to his wife, but the contrasting "masculine" first part shows a less appealing view of the gender distinction. The latter reminded me at one point of the distress expressed in another Viennese piece, Verklaerte Nacht. Technically, Pelinka notes, the piece progresses in a series of pedal points.

Betty Beath's Lagu Lagu Manis II, meaning "sweet melodies," was inspired by the memory of fragments of melodies heard in Bali and Java. Tonally, the Australian composer says her work is based on one of the characteristic Javanese gamelan scales but that her interpretation of the music is more Balinese. The piece is pleasurable and melodic, with trilling flute, light percussion, and legato string melody. Increased dynamics are augmented with horn. There is thematic development and even some counterpoint.

Juhani Nuorvala's Notturno urbano is perhaps misnamed, even as an urban nocturne, because it is brash and noisy, except for a nice slow quiet passage halfway, in which the composer suggests the song of a nocturnal bird. My own experience of large cities is that they tend to be quiet at night (as expressed in Copland's Quiet City) but perhaps Nuorvala means to suggest the interior nightlife of certain clubs. The nine-minute work begins with a siren-like theme and becomes shrill and jagged with brass and loud drum beats. A nearly frantic passage becomes faster and faster and the work ends with a quick bang.

Mary Mageau's tonal piano concerto, The Furies, is in three-movements, each named for a particular Greek mythical figure. The Furies were gods or demigods of vengeance from the Underworld, best known for pursuing Orestes in Greek myth and drama after he killed his mother for the murder she committed. Symbolically, the Furies are sometimes interpreted as representing human conscience, which appears to be Mageau's intention here. Personally, I always imagined the Furies to be rather like the swarm of bees I once saw relentlessly pursuing an unfortunate boy whom they knew had disturbed their nest. These particular Furies, whom I was not able to find listed in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, may be relentless, but not so fast paced or furious as those bees. The middle of the first part, Alecto, is so lyrical, relaxed and downright lovely, that one could accuse the Fury of sitting down on the job. It does begin more furiously and ends with a sudden pounce, though. Full use of the orchestra is made. The piano part seems somewhat more detached. Tisiphone, the middle Fury, begins ominously, with brass, and maintains suspense until the piano enters quietly and tentatively until the first crescendo (of two). The piano part is good, but its dramatic role is again elusive. The movement eventually ends quietly. The final movement, Megaera, is loud from the start, the pace brisk, and the piano is lively – even bouncy – this time, and much more part of the dramatic action.

Given the right choreographer and designer, The Furies might well make an effective ballet.

The performances and recording in this collection are uniformly excellent, to my ears, and I can recommend the disc without hesitation.

Copyright © 2012, R. James Tobin