The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

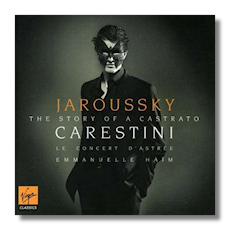

Carestini

The Story of a Castrato

- Nicola Porpora: Siface: Tu che d'ardir m'accendi

- Giovanni Maria Capelli: I fratelli riconosciuti: Ciel nemico

- George Frideric Handel:

- Arianna in Creta: Qui ti sfido

- Ariodante: Scherza, infida

- Alcina: Sta nell'Ircana; Mi lunsinga

- Leonardo Leo: Farnace: Se mi dai morte

- Johann Adolf Hasse:

- La clemenza di Tito: Se mai senti; Vo disperato a morte

- Christoph Willibald von Gluck:

- Demofoonte: Sperai vicino il lido

- Carl Heinrich Graun:

- Orfeo: Mio bel nume; In mirar la mia sventura

Philippe Jaroussky, countertenor

Le Concert d'Astrée/Emmanuelle Haïm

Virgin Classics 3-95242-2 DDD 72:06

French countertenor Philippe Jaroussky astonishes once again with a program of arias associated with castrato Giovanni Carestini. At the peak of Carestini's career, his supremacy was challenged only by that of Farinelli, the other reigning castrato of the era. Frédéric Delaméa's extremely informative booklet note relates that contemporary opinion, while it held that Farinelli had more technical facility, was that Carestini used his voice more expressively than Farinelli. Charles Burney wrote, "Carestini gratified the eye as much by the dignity, grace, and propriety of [his] action and deportment, as the ear by judicious use of a few notes within the limits of a small vocal compass."

Carestini, who was born in 1700, enjoyed a 38-year career, which is impressive even by modern standards. As a teenager, he acquired the patronage of Cardinal Agostino Cusani of Milan. From his debut in Milan, he traveled to Rome, Parma, Naples, and the other major musical cities in Italy. When he was 32, he went to London, where he spent two seasons singing roles written specifically for him by Handel, and creating a sensation. He then returned to the European mainland, and conquered new territory, including Dresden, Berlin, and, near the end of his career, St. Petersburg. Apparently, by 1758, his voice, heretofore carefully preserved, gave out, and his last appearance in Naples was a failure. "He withdrew immediately from public life," writes Delaméa, "and died two years later."

This program is in chronological order, from Porpora's Siface, in which Carestini appeared in 1725 or 1726, to Graun's Orfeo, which was premièred a quarter-century later. Most of these areas are unfamiliar, but certainly worth any listener's attention. I was particularly drawn to the two closing areas from Orfeo. For the most part, the Baroque revival has not yet caught up with Graun. We are due for major new productions of his operas, particularly the outstanding Montezuma (to which Joan Sutherland and husband Richard Bonynge briefly turned their attention in the 1960s). The first aria presented here, "Mio bel nume," is profoundly moving, and "In mirar la mia sventura" is a fiery virtuoso piece.

And Jaroussky … well, what a voice! No other countertenor at work today produces a sound of such beauty and touching clarity. It isn't a masculine sound, to be sure, but neither is it disconcertingly feminine – it's really in its own category. (His speaking voice, by the way, is clearly male.) As such, it might take some getting used to, but once you do, I expect that you'll find yourself often moved to tears by its purity, and also impressed by its range. Also moving is the effortless manner in which he deploys it, even in the most complicated music. It would be wonderful to know what Carestini sounded like, but given Burney's description, is it not possible that Jaroussky would have given Carestini a run for his money?

Emmanuelle Haïm and Le Concert d'Astrée provide Jaroussky with stylish and scholarly support, as does the engineering team. In addition to the aforementioned booklet note, there are complete texts and English translations. In the last aria, though, surely stigi should be translated as "Stygian" not "Scythians," no?

Copyright © 2008, Raymond Tuttle