The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Copland Reviews

Menotti Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

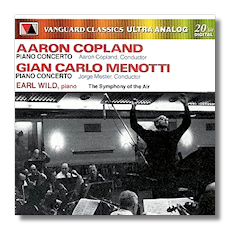

Copland / Menotti

Modern Piano Concerti

- Aaron Copland: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra

- Gian Carlo Menotti: Concerto in F for Piano and Orchestra *

Earl Wild, piano

Symphony of the Air/Aaron Copland

* Symphony of the Air/Jorge Mester

Vanguard Classics VC3 (formerly OVC4029) 49:23

Summary for the Busy Executive: Skyscrapers and Scarlatti.

ArkivMusic has quietly (and legally) restored to the catalogue thousands of classic recordings the major labels have dropped. I bought the original Vanguard MONO LP of these concertos in my teens, mainly for the Menotti. I had seen a local production of The Medium which spurred me to the Cleveland Public Library, where I checked out the score and the recording with Marie Powers. At that point, I really had little idea of Menotti's place in the musical world, or even that he was thought of as an opera specialist. After all, hadn't he written this concerto? I quickly found out that people who knew something about music looked down on him, but that didn't stop me from liking – a lot – what I heard.

It turns out that for most of his life, Menotti longed for a critical success like those enjoyed by his friend Samuel Barber, while Barber yearned for a popular success like Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors. Menotti probably came closest to what he wanted with his violin concerto (1952). Still, I've always liked the 1945 piano concerto even more. Formally, it's a bit of a mess, like a rumpled but favorite uncle, but it doesn't seem to matter – at least not to me. In its spirit and its contrasts, as well as in the general shape of some of its themes, it recalls very strongly Ravel's G-major concerto. It's just not as elegant or as brilliant a composition. Few other pieces (by anybody) are. What it does have are tunes, tunes, tunes – memorable tunes, tunes that ravish the ear, tunes that make you feel great, tunes that you find yourself humming for days, months, and years afterwards. The concerto proceeds in a straightforward way, with quick sections framing and balancing lyrical ones. The first movement explodes into a fugato with exuberant Scarlatti-like runs in the piano. A song-like section follows, and we end up with a recap. The slow movement is nine minutes of gorgeous, melancholy song. The finale – which I would call a rondo in a more solidly-constructed work than this – builds up to a bring-'em-to-their-feet ending. Menotti may not be Brahms, but he might very well be Grieg, and that's not nothing.

Of course, the Copland takes a much thornier approach, although it's not without considerable humor. However, where Menotti gives you the impression of just singing the song that lives within him, Copland consciously tries to carve out his own niche in Modernism. An early work (1926) written under the influence of both Stravinsky and Gershwin (the Concerto in F appeared in 1925), it shows a young man's desire to be taken seriously. I don't know how the first audiences took it, but it thrilled me from its opening bars. Like the Gershwin concerto, it shouts "New York!" from its first measures, with thrusting upward leaps followed by soaring cantabile. This is not the folky Copland of the "American" ballets, but you recognize the composer nevertheless. Jazz was still in the air, and Copland at this stage explored it as a way of writing characteristically American music. He gave it up shortly thereafter. Copland divides the concerto into two related parts, played without break, and writes extremely tersely. Each note says a lot. There's also a funny, jazz-vamp section, initiated by solo piano, with a melody that foreshadows the 1944 Jule Styne song, "Poor Little Rhode Island." It stands out so that you wonder whether Styne had ever heard the Copland. The soloist often gets to lurch into his part, as if drunk, dull-witted, or simply not very good, but it's all written in and indeed constitutes part of the rhythmic challenge of the concerto.

One associates Earl Wild with Liszt and Rachmaninoff, rather than with modern music (other than Gershwin), but he turns in a marvelous performance of both concerti. The Menotti fizzes and sings with a light touch, and Jorge Mester matches Wild with an accompaniment that sparkles. My only reservation is Copland and the Symphony of the Air. Copland can't keep the cross-rhythms in his own concerto quite together, and the orchestra sounds in spots like they're holding on. I did prefer Bernstein's recording with Copland as soloist (Sony 60177 or 2-CD set Sony 47232; the latter has a bunch of early Copland, 1923-1935) – broader, fuller-sounding, and rhythmically more compelling.

The Vanguard sound as presented on the CD improves on my LP enormously. In fact, the tinny, puny scratch from my record player led me to seek out the Copland/Bernstein in the first place. The CD incarnation is both rich and clear as a bell.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz