The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weinberg Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

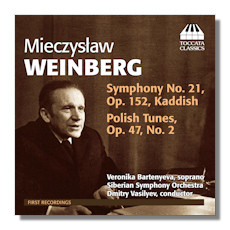

Mieczysław Weinberg

First Recordings

- Symphony #21 "Kaddish", Op. 152 *

- Polish Tunes, Op. 47 #2

Veronika Bartenyeva, soprano*

Siberian Symphony Orchestra/Dmitri Vasilyev

Toccata Classics TOCC0193 67m

In my other recent reviews of symphonies by Mieczysław Weinberg, I noted his stylistic debt to his friend Shostakovich. The more you listen to Weinberg's music, however, the more you realize that he stood mostly independent of Shostakovich or any other composer. True, his orchestration and overall style still undeniably divulge ties to Shostakovich, but then, to be fair, Chopin can be heard in Liszt – and Brahms in Dvořák. At any rate, Weinberg in his Symphony #21 will again call to mind the style of Shostakovich in a few passages, but he is far more bleak and despairing than Shostakovich ever was in any of his fifteen symphonies. And that's saying a lot when you consider the angst and suffering expressed in works like the Shostakovich Symphonies 8, 13 and 14. Those familiar with Shostakovich's Fifteenth String Quartet, however, will get an idea of the tragedy and anguish expressed in Weinberg's Symphony #21, a work subtitled "Kaddish" (the Jewish prayer for the dead) and dedicated "to the victims of the Warsaw ghetto." Thus, it is music inspired by the horrendous treatment of the Jewish population in Warsaw during World War II at the hands of the Nazis. Weinberg knew the suffering firsthand, as he was from Warsaw and lost family members there during the Nazi occupation.

To call the music in the Symphony #21 bleak and somber or sad and heartrending would only approximate its extremely tragic character. Cast in a single movement, but in six sections, the work features a pair of dark recurring themes – one a variant of the other, actually. It also briefly quotes Chopin – the Ballade #1, played very slowly and appearing in the opening and closing sections. Weinberg also quotes himself – his Fourth String Quartet – in section two. The work is mostly slow throughout the fifty-four minute duration of the symphony, though there is some lively music both in the second section (Allegro molto) and in the three-minute Presto comprising the fourth section. Soprano Veronika Bartenyeva sings with utter commitment in the finale, matching the intensity and harrowing character of the music in her wordless singing part. Her performance is arresting as it grows in intensity conveying music that is eerie-sounding, ghostly and finally angry. Weinberg's writing here is similar in character to that of Vaughan Williams in his 7th Symphony (Sinfonia Antartica), which also features wordless music for a soprano. But that tragic work at its grimmest doesn't quite match the darkness and horror here. Ultimately, one can fairly say that Weinberg's 21st symphony is not for the faint-hearted. Indeed, it's strong stuff, deep and profound, unsettling and thought-provoking.

All this raises some thorny questions: we all listen to music for enjoyment, for pleasure, right? But can a composition that expresses such abject suffering and horrendous injustice be enjoyable? True, opera features music – much of it with catchy tunes and colorful orchestration – that depicts murder, nasty intrigues and illicit affairs. But we know that it's not real, that the singers will all take a bow at the end and we'll cheer for them. But you won't be cheering at the end of Weinberg's symphony because its music is all too real: its victims are real; its villains are real. Weinberg doesn't want the suffering and injustice in the Warsaw ghetto to be forgotten. To that end, he has succeeded: his symphony will offer an artistic redress that can enrich and enlighten those willing to open their hearts and minds to the work's tragedies. It may just offer a cathartic sort of satisfaction.

The Polish Tunes, Op. 47 #2 is hardly similar to its discmate. In fact, it's quite the opposite, but it makes a good coupling as its inspiration comes from Poland as well. Its four numbers together last just under fourteen minutes and offer a world far removed from strife and suffering: moods are uniformly chipper and festive; tunes are folkish and catchy; and the orchestration is colorful. This is the kind of work that makes you wonder why you haven't encountered its music before in concert or on disc.

In both works Dmitry Vasilyev draws fine performances from the Siberian Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble that sounds quite talented collectively, totally unlike some of the unpolished orchestras that appeared on countless Soviet-era recordings in the 1960s and 1970s. The orchestra is known within its own borders as the Omsk Philharmonic, and can be found more easily under that name on the web. Toccata Classics offers excellent sound reproduction and very enlightening notes by David Fanning. Recommended.

Copyright © 2014, Robert Cummings