The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Spratley Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

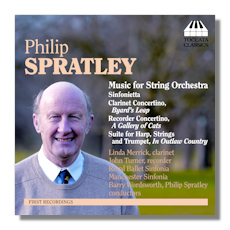

Philip Spratley

Music for String Orchestra

- Sinfonietta, Op. 6 *

- Clarinet Concertino "Byard's Leap", Op. 27

- Recorder Concertino "A Gallery of Cats", Op. 26

- Suite for Harp, Strings & Trumpet "In Outlaw Country", Op. 12b

Linda Merrick, clarinet

John Turner, recorder

Tracey Redfern, trumpet

Eira Lynn Jones, harp

Manchester Sinfonia/Philip Spratley

* Royal Ballet Sinfonia/Barry Wordsworth

Toccata Classics TOCC0088 2009 71:11

Summary for the Busy Executive: Not only delicious, but satisfying.

Multiply the number of composition programs in conservatories, colleges, and universities worldwide by the number of graduating students, and you get a fair idea of the staggering number of composers produced each year, not including the self-taught, the amateur, and the weekend warrior. Multiply that by a "generation" of thirty years, and you begin to realize how many of them compete with one another. There are so many, no one can possibly have heard them all, so the comforting adage, "Cream always rises to the top," really doesn't mean much.

Of course, not everyone becomes Stravinsky or Vaughan Williams or Schoenberg or Webern, but I think it inevitable that we have hooked onto, for a while, at least some prominent nonentities. I can't name them because I can't predict the future, and – who knows? – they may turn out to be composers I like a lot. Unfortunately, we seem to be able to keep only a few great composers in our head at a time. If, for example, most of us listed off the top of our heads the greats from Beethoven through Mahler, how many of us would include Schubert, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Liszt, Schumann, Mussorgsky, Smetana, Dvořák, Grieg, or Fauré, let alone Hummel, Vořišek, Rimsky-Korsakov, or Chabrier? Would Tchaikovsky go significantly missing? At any rate, room at the top is cramped.

So all praise to Toccata Classics for its commitment to recording music that deserves a shot and has mostly gone unheard and for the high interest of its books and CDs. This latest features composer Philip Spratley (b. 1942). I fancy I know a lot about Modern and Contemporary British music, but I had never even heard of Spratley or of the men who taught him.

In many ways, Spratley's music looks back to classic British Modernism – a combination of Holst and Britten – a clean, neoclassical approach to form with some significant folk influence. With the exception of an unperformed violin concerto (and I hope that changes soon), he has confined himself mainly to smaller forms, probably because his having to earn a living at something other than composing has cut down on his time and because of his compulsion to work only when inspired. It shows. The level of invention is amazingly high. However, inspiration doesn't strike all that often. Most composers with large output tend to slog their way through a piece, keeping the lines of inspiration open so that when it does strike, they can take advantage. However, what sticks with me most, in retrospect, is the way Spratley's works tend to begin. He usually does not present an arresting, grand statement, as we find in something like Bloch's Concerto Grosso #2 or Britten's Simple Symphony. Instead, he clearly and with little hoopla states an idea which grows in significance as the work progresses. It reminds me of meeting a self-effacing sort who turns out to be the most interesting person in the room.

The earliest score here, the Sinfonietta (revised to its present form by Spratley in 1987), has four movements. The first, a sonata, runs the longest and interests me the most. The main theme never leaves for long, and the movement boasts some arresting gigue-like fugato passages. The second movement, marked "Arioso," opens with a solo violin, joined by solo viola and solo cello. It sings of "noble grief" before going into a pastoral 6/8. It climaxes in ways reminiscent of the more passionate sections of Vaughan Williams's Tallis Fantasia, without ever imitating. Throughout, one comes across unusual, poetic string textures. It ends with the solo trio, each member dropping out in reverse order of entry. The third-movement "Scherzo" the composer intends as humor. It's certainly high-spirited, but it hits me more with its vigor, rather than with its humor. The trio struts before the scherzo returns to a breathless conclusion. The finale starts out quietly, but soon becomes almost madcap, with fairly strong syncopations that seem to want to tear through the rhythmic fabric. The movement stamps its way to the conclusion.

The subtitle of the Clarinet Concertino, "Byard's Leap," has to do with a tale of a horse who escaped a witch. Spratley relates a loose program in his liner notes, but the score makes good effect even if you (like me) have never of Byard. A mini-solo for the clarinet opens the first movement, which sings in a quasi-"gypsy" way, all the while avoiding predictability. The slow movement, "Larghetto e desolato," lives up to its billing. It moves at the pace of a chaconne, with wintry shivers from the strings. The finale, another triple-time romp (mainly 9/8), leaps about both melodically and harmonically, emulating Byard.

The Recorder Concertino, A Gallery of Cats, consists of mini-movements (none longer than about 3½ minutes) – a suite, really. The title somewhat misleads, since the Spratley specifies four different recorders: soprano, alto, tenor, and sopranino. The composer is, apparently, a "cat person," who confesses that he has rarely gone without the company of more than one at a time. Cats do seem to proliferate throughout a house more than dogs. Anyway, Spratley offers cameos of some of his favorites through the years. Of course, these portraits mean something only to Spratley and to his immediate (human) family. The question becomes, do these movements work on their own? Of course they do. Spratley creates a suite of attractive dances, which along with his subtitle, manage to suggest feline movement.

The Suite In Outlaw Country (how does Spratley keep coming up with such marvelous titles?) points not so much to outlaws as to "country," the area around Lincolnshire, home of Robin Hood. In addition to strings, the composer offers extensive roles for harp and trumpet. Spratley has a genuine "feel" for nature while keeping the music free of Impressionist, British Pastoral, and Romantic clichés. One hears, above all, an individual voice. The first movement evokes briefly a battle of the English Civil War, the second a walk by the Trent, the third the bustle of market day (with the hymn-tune "Southwell" mixed in), the fourth a church near Byron's ancestral home during Christmas, and the fifth a Maypole dance (with a return to "Southwell"). As Spratley puts it in his liner notes, "The … tune is heard in its full glory as sacred and secular are joined together in a rousing finale."

Spratley is a wonder. Each piece is beautifully worked and a delight to ear and spirit, even if its artistic ambitions fall short of a Beethoven symphony. You need command of a real gift to write light music of this caliber – that is, light in texture, modest in scope, but emotionally penetrating and mentally stimulating. The performances sparkle. Barry Wordsworth, a conductor I've faintly praised in the past, not only gives the Sinfonietta its due, but raises it to something more intense than its forces suggest. He makes me long to hear that violin concerto. Spratley as conductor serves the composer as he mines depths that would surprise a mere reader of the liner notes. The soloists give fine accounts all around. I have always admired recorder virtuoso John Turner as an adventurous musician who looks into obscure musical corners. This CD made me light up. Give it to yourself for Christmas, if you've been good.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz.