The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Beethoven Reviews

Thalberg Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Works for Piano

- Ludwig van Beethoven:

- Piano Sonata #7 in D Major, Op. 10 #3

- Piano Sonata #9 in E Major, Op. 14 #1

- Piano Sonata #10 in G Major, Op. 14 #2

- Sigismund Thalberg:

- Souvenirs de Beethoven "Grande Fantasie pour le piano sur la 7e Symphonie de Beethoven", Op. 39

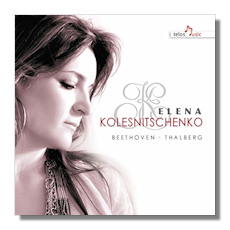

Elena Kolesnitschenko, piano

Telos TLS194 73:23

Elena Kolesnitschenko was a brilliant child prodigy, giving her first concerts in 1991 at age nine at the United Nations in New York and at the Vatican before an audience that included Pope John Paul II. At 18 she began studies at the Hannover Academy of Music in Germany, where her teachers included Vladimir Krainev. She went on to win prizes at important international competitions and has apparently developed a major career as a concert pianist. By the way, her Facebook page transliterates her name as "Kolesnichenko", but I'm using the spelling on the album jacket and in the accompanying booklet.

Kolesnitschenko has a fine grasp of early Beethoven: too many pianists try to highlight the music's supposed epic character or plumb its depths for profundity that isn't necessarily there, but Kolesnitschenko typically points up the music's fleet and youthful energy in the faster sections, while employing a crisp, almost blunt approach in darker and slower music. It's a lighter treatment, to be sure, but one that works brilliantly here. I'm sure pianists like Alfred Brendel would approve of Kolesnitschenko's way with Beethoven. She understands that the composer of Sonatas 7, 9 and 10 was not yet the mature Beethoven, the fellow who wrote the Waldstein, Appassionata and Hammerklavier sonatas. Granted, there are only four years separating the composition of #10 and the Waldstein (#21) – four years but nearly forty opus numbers!

Notice the effervescent drive and vivacity of Kolesnitschenko's Rondo finales in #7 and #9: there is such a delightful energy and lightness in her breathless tempos and sense of playfulness. Her playing is generally fast, but never sounds rushed: she makes just about the best case possible for her brisk approach with subtle phrasing that includes a wide range of dynamics which tend to favor the softer end of the spectrum. True, there's little muscle here, but there's much elegance and subtlety, traits more appropriate in these early Beethoven works. Actually, the music in her hands often sounds airy, almost ethereal, but when darker elements appear, as in the Largo of #7 or in the first movement of #10, she does not shortchange the music's impact: tempos become less driven or at least more elastic to allow for additional weight and to italicize dramatic moments. She is always both intelligent and sensitive in her phrasing of virtually every passage in these Beethoven sonatas. From the evidence here, one can safely assert she is a major artist, at least in the works of Beethoven.

Her Thalberg is more muscular and darker, and points up a Lisztian side to the composer. It is just as convincing an approach because this takeoff on Beethoven themes from the Seventh and Fifth Symphonies is a big Romantic and dramatic fantasy piece that truly storms the heights, while also inflating things and going a bit over the top, much as Liszt often did in his numerous paraphrases and fantasies on the themes of other composers. Kolesnitschenko's performance demonstrates that she has the ability to change her interpretive persona to suit the music. Again, she is brilliant.

What is amazing about these performances is that they are live efforts, derived from the 2014 Böblingen International Piano Festival in Germany. Further, it appears there may be no edits as there is a seamless flow of moving from one work to the next after applause, thus creating the impression the performances may have all been taken from the same live concert. If that is so, then this is all the more amazing. Kolesnitschenko's accuracy and seeming ease of execution in these difficult works are simply stunning. Incidentally, this is one of several discs on the Telos label featuring Elena Kolesnitschenko in piano sonatas by Beethoven. All thirty-two will be recorded but with several pianists involved in the project.

Copyright © 2015, Robert Cummings