The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

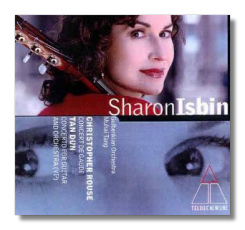

Contemporary Guitar Concerti

- Christopher Rouse: Concert de Gaudi

- Tan Dun: Concerto for Guitar and Orchestra [Yi2]

Sharon Isbin, guitar

Gulbenkian Orchestra/Muhai Tang

Teldec 8573-81830-2 56:08

Summary for the Busy Executive: Castanets and p'i-p'a.

Christopher Rouse and Tan Dun have hot careers right now, and at least one of them deserves his. I must say that no work I've heard by Tan Dun has impressed me enough to want to hear it twice, and this concerto proves no exception. The liner notes blather about both composers' "philosophies" (Right. Like Leibnizian monism, I suppose. Does anybody, other than the composers' mothers and objets d' affection really care?). Better the writer tried to clarify the music, but this is just a minor annoyance.

Tan Dun could believe the moon was made of green cheese, and I wouldn't think twice about it, if his guitar concerto didn't bore the bejeezus out of me. In a work lasting nearly half an hour, less than a third (the "Andante agitato" section) demonstrates any movement or rhetorical contrast at all. In other words, the rest of it could have been written by a synthesizer keyboard, a MIDI sequencer, and a chimp. Not quite fair, since the orchestration shows some imagination, but you can't rely on that for a thirty-minute piece. You might as well watch paint dry. In general, Dun's music doesn't like to move, and it always seems a Big Deal when it does, like trying to push a truck uphill or like Tchaikovsky modulating to another key. The mountains shudder, the earth trembles, but usually only for a couple of minutes. At least Tchaikovsky knows that he needs to go from here to there, and he succeeds, often by brute force, if nothing else. I get the impression Dun doesn't believe transformation or transition necessary. Music for him seems to reflect an unchanging state of mind. This may work for Chinese music (I don't know whether I've actually heard the real thing), but not for most listeners in the West.

Rouse's music, on the other hand, moves like gangbusters, and from the opening bars, to boot. Curiously, Rouse's beginning resembles Dun's – a stentorian announcement from the solo guitar. They differ in that Rouse's music keeps on going. A composer of guitar music avoids the Spanish and Latin-American idioms with difficulty, and Rouse in the first movement gives the Spanish idiom a big, fat hug – Falla and Rodrigo on steroids. But something seems to happen during that movement's course. The Iberianisms, though still present, seem to melt and morph into something else, something more fluid and at least a little unsettling. One can say the same for the reflective slow second movement, inspired at least in part by Gaudi's Temple de la Sagrada Familia. It starts out in the same psychological territory as the famous slow movement of Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez, but the same thing happens. We quickly find ourselves in a realm of phantoms. Indeed, the concerto reminds me of Sagrada Familia itself – sharp images emerging from and sucked into a structure apparently built from fungal flesh. The third movement gives us more of the same, this time with pyrotechnical opportunities for the soloist. Rouse, like Falla before him, has brilliantly rethought the Spanish idiom to come up with something individual. When he brings back the concerto's very first idea, he immediately transforms it, and by this time it seems like the most natural thing in the world.

Sharon Isbin seems to me (a non-player) a great technician, but more importantly a brilliant musician as well. These aren't easy pieces for performers to get their minds around. Both Isbin and conductor Muhai Tang make music – as best they can in the Dun, and brilliantly in the Rouse. Despite my obvious dismissal of the Dun, the Rouse alone justifies the money I spent. The sonic image – the combination of guitar with orchestra is notoriously difficult – sounds, again, "natural," even though at least one brilliant engineer sweat to set it up.

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz