The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Mendelssohn Reviews

Tchaikovsky Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

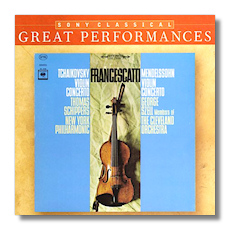

Classic Violin Concertos

- Felix Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 *

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D, Op. 35

Zino Francescatti, violin

* Cleveland Orchestra/George Szell

New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Thomas Schippers

Sony 82876-78760-2 57:19

Summary for the Busy Executive: More from Sony's Great Performances series, and it definitely lives up to the advertising.

Zino Francescatti (despite the Italian name, born in Marseilles) stands as a distinguished representative of the French school of violinists. As opposed to a Heifetz or a Stern, for example, Francescatti sang with a tone lighter, cooler, and more lyrical. Today, I imagine the analogous contrast as Vengerov vs. Hahn, although Hahn studied with Brodsky. Currently, she's closer to Francescatti's playing than to Perlman's.

What with every pint-size Heifetz essaying the work, mainly because it lies so well under the fingers, the Mendelssohn concerto threatens to become the Rodney Dangerfield of the violin repertoire. By the way, Heifetz himself first publically performed the concerto at age seven. Francescatti and Szell rescue it from the prodigies and force the listener to acknowledge a masterpiece. This concerto suits Francescatti's general approach like oysters in gumbo. Though trouble disturbs the undercurrents of the first movement, its overwhelming characteristics are clarity, economy, and poise. Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra make the ideal partners. This performance simply crackles with excitement – from Francescatti's piercing tone and ensemble alertness to the orchestra's rhythmic propulsive snap, particularly from the woodwinds. If Erick Friedman and, believe it or not, Ozawa with the London Symphony count as my favorite recording (not currently available) of the dozens I've heard, Friedman is mainly the reason. He plays with an intensity that burns into your soul. Nevertheless, Francescatti's is probably my second-favorite account. I've loved it since I bought the original LP. It hovers between Classical balance and Romantic ardor. The force of it derives as much from something like Mozart's g-minor Symphony #40 as from middle and late Beethoven, that no-man's land between two eras where Mendelssohn's power lies. Its modernity derives from its self-conscious formal innovations: its ruthless clarity and drive toward unity. Not only the famous connecting progression between the first two movements, but even the cadenza, normally a suspension of symphonic argument, become its servant, effecting a genuine transition between development and recapitulation. The same rhythmic motifs show up in all three movements, further binding the concerto. The second movement, beginning with a characteristically "sweet" idea, reminiscent of some of the Lieder ohne Worte. A middle section of surprising depth breaks in, and both Francescatti and Szell raise their game without sacrificing their fundamental elegance. Commentators have likened the third movement, an ingeniously modified rondo, to the Midsummer Night's Dream overture, but there's nothing fey about Szell and Francescatti's full-blooded account. They manage to achieve a sinewy wit.

The Tchaikovsky would appear to lie outside Francescatti's natural range, as the Russian concerto par excellence, but the violinist makes a very fine showing. Schippers and the New York Philharmonic give him plenty of help, and, as with Szell, Francescatti becomes a partner (although a very senior one) rather than a star. One can find finer accounts, but this has nothing to apologize for. Francescatti stands up to the weight of the orchestra without sacrificing his grace. Compared to other soloists, he plays with chaste restraint, going less for the wow than for the purely musical qualities of this masterpiece of a concerto. This comes out most strongly in the first-movement cadenza, where he proves he has not only the fingers but also the insight, and in the slow movement – in my opinion, the height of this collaboration. The New York Philharmonic at this point in their history won no points for precision, and when Schippers presses them in the outer movements, their rhythm and attack go spongy. In the slow movement, you get the equivalent of a Vulcan mind-meld, and the reading immediately deepens without falling into a tub of chicken fat.

The sound is definitely of its time and label – Columbia in the early stereo era: goosed bass and the soloist too forward. But sparks do fly here, with the Mendelssohn outstanding and the Tchaikovsky quite fine.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz