The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

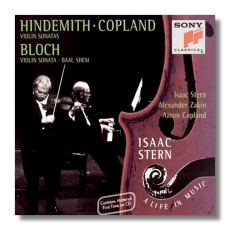

Isaac Stern

Modern Music for Violin

- Paul Hindemith: Sonata for Violin and Piano (1939) (mono)

- Ernest Bloch:

- Sonata #1 for Violin and Piano

- Baal Shem: Three Pictures of Chassidic Life

- Aaron Copland: Sonata for Violin and Piano *

Isaac Stern, violin

Alexander Zakin, piano

* Aaron Copland, piano

Sony SMK64533 62:15

Summary for the Busy Executive: Maddeningly inconsistent.

Volume 28 in Sony's retrospective on Isaac Stern premières on CD rare items from the violinist's catalogue. I had the LPs (naturally) and pounced on this album as soon as it hit. I've always liked Stern in modern repertoire. His LP coupling of the Barber and Hindemith concerti ranks among my favorite albums. On the other hand, I've never really cared for his interpretations of the Romantic war-horses. There's nothing wrong, but nothing particularly revelatory either. I suspect he goes mainly on instinct, and like most instinctual art, success is more hit-or-miss than with a more intellectual approach. At least the latter gives you greater consistency.

Stern here delivers three smashing hits and a surprising miss, all with music found on roads less traveled-by. Hindemith, as we know, wrote at least one sonata for the standard orchestral instruments. He wrote several for the violin (including for solo violin), and this one is, I believe, his last. It falls well within his maturity, when he brought his musical language to the height of its beauty. An extraordinarily shapely work full of interesting and powerful ideas, the sonata exploits the contrast between martial and meditative moods. Stern and Zakin play with great verve and Zakin also with great delicacy. Stern in the quieter sections does well, but in a less studied way. He achieves the trick of sounding as if the music were the most natural thing in the world. As I think about it, Zakin may hover a bit too much in the background - whether due to the engineer or to his own machinations, I don't know. You can hear everything, but you long for more of an equal partnership.

The Bloch for me represents the high-water mark of Stern's playing. The first sonata and Baal Shem come from roughly the same period, the early Twenties, just a few years after Bloch's Schelomo. Bloch doesn't get much play these days, to me the culture's serious omission of a major composer. I suspect the fact that he founded no school or international style has militated against him among those who consider influence a necessary criterion of greatness. I admit he also has some huge howlers in his catalogue (notably America, an Epic Rhapsody), but then again so do Beethoven, Wagner, and Brahms. We should judge composers by their best. There's little point in judging them by their worst, except to allow ourselves to feel momentarily superior. If you have a feeling for the music of the period, the two works will immediately strike you as both powerful and thoroughly individual. You don't get School of Strauss, Schrecker, and Zemlinsky, Stravinsky, Bartók, Debussy, Hindemith, or Schoenberg. It's not even an individual dialect of an established language, but really a new language in its own right. The first violin sonata is, according to me, one of the great works of the century, and very few know it. It opens with a wallop: savage, violent, and sensuous at the same time. Unlike Bloch's best-known works, there's nothing particularly "Jewish" about it. Indeed, the music seems to sing of a place and time older than Judaism. From the view of compositional technique, it's a wonder - lots of little cells combining and recombining into new themes and somehow these aggregates related to one another in sonata form - but technique isn't what hits you first. You can enjoy this piece without knowing sonata from sonar. It's the passion of it that grabs you and doesn't let go.

Bloch responded to his publisher's request to write some short pieces for the violin with Baal Shem. The scale may be smaller than in the sonata, but the emotional impact strikes almost as hard, way beyond what expects from the length. Bloch found his inspiration for this work in Jewish life and finds his musical material in the form of cantorial chant and Yiddish folk song. Except at the end of the last movement, he avoids direct quotation. Elgar, once asked about folk song, replied, "I write the folk songs of this country." Bloch here writes his own as well. The second movement, titled Nigun ("Improvisation" or "prayer"), is the most elaborate. I believe Bloch also orchestrated it, and it shows up once in a blue moon on concert programs. The final movement, Simchas Torah, Bloch translates as "Rejoicing," but it is really the name of the Jewish holiday which celebrates the Torah, the book of Jewish law. The music is an ecstatic dance, occasionally breaking out into full-throated ardent song. Stern and Zakin let 'er rip. The balance problems that slightly dim the Hindemith have disappeared. This is, to me, one of the classic performances of the stereo era. Really, if all you know of Bloch is the magnificent Schelomo, give this CD a try.

On the other hand, the Copland disappoints big-time. I can't say whether it's the piece itself (I've heard only this performance) or Stern. Since the sonata comes from Copland's most gorgeous musical period (Appalachian Spring, Rodeo, The Red Pony, Symphony #3, and so on), I strongly suspect Stern. The notes are there, of course, but just the notes. Stern misses the ardor of Copland's lyricism as well as the shape of the phrases. In the general cluelessness, Stern's performance here reminds me of his embarrassing recordings of the Bartók sonatas. Copland accompanies and supplies all the poetry and coherence of this account. It gets a bit frustrating. Copland will lay open this gorgeous lyric phrase, inviting Stern to expand and intensify, and Stern blands it up. Surely Copland had the clout to choose whomever he wanted. I wonder why he chose Stern.

The sound is fine, if not spectacular. Even the monophonically-recorded Hindemith sounds quite good.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz