The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

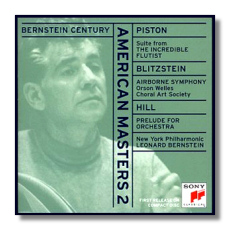

Bernstein Century

American Masters 2

- Marc Blitzstein: Airborne Symphony

- Walter Piston: The Incredible Flutist *

- Edward Burlingame Hill: Prélude for Orchestra **

* Orson Welles, narrator

* Andrea Velis, tenor

* David Watson, baritone

* Choral Art Society

New York Philharmonic Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein

** Columbia Symphony Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein

Sony Classical SMK61849 ADD **Mono 78:09

Summary for the Busy Executive: When we were young.

I've just finished listening to the ten-part Leonard Bernstein radio documentary on my local NPR station. A lot of it seemed empty fawning, and I like Bernstein. But a man should be protected from his friends. At any rate, I got to hear a lot of Bernstein's music, always a good thing. Above all – despite the cribs from Stravinsky, Hindemith, Copland, Foss, and other bits and pieces – it struck me as brilliantly individual, immediately identifiable as Bernstein. How he could take such a mix and make it his own borders to me on the miraculous. With a Bernstein piece, you at least can't complain that you don't know what you're getting.

Before hearing this CD, I hadn't realized how much Bernstein programmed his youth (or at least his adolescence), especially as far as American music went. Copland, of course, became a friend. Piston and Hill stood among Bernstein's Harvard teachers. Diamond helped him with his scores early on. Blitzstein met the Harvard student Bernstein, who had gotten up a performance of the older composer's "union opera," The Cradle Will Rock. Bernstein came up in the Thirties and retained to the end of his life a belief that art should make a better society. His witty characterization of Copland's music as coming from an Old Testament prophet masked, to a great extent, the way he viewed himself. Just think of almost any of his Big Pieces: the "Jeremiah" Symphony, the "Age of Anxiety" Symphony, the "Kaddish" Symphony, Facsimile, Mass, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue / White House Cantata, Arias and Barcarolles, Songfest, even the "little" opera Trouble in Tahiti. Every single one of them speaks to a broken culture. The major exception seems to me the Serenade, from Plato on love.

I keep hearing that The Incredible Flutist ballet – about the circus that came to town – is Walter Piston's most popular work. If I compare it to the symphonies, concerti, and chamber music, it seems rather bland to me, but why deny people their fun? I imagine the genuine naïveté of the ballet makes up a large part of its appeal. The major tune in it is a soulful tango, and Bernstein rightly emphasizes its schmaltz. Well, maybe "schmaltz" isn't the right word, since it implies manipulation, and both Piston and Bernstein embrace the piece without cynicism. On the other hand, Bernstein reveals nothing not found in other recordings. Unless totally hipped on Bernstein, you probably wouldn't buy the CD for this work.

I'd say the same for the Hill. Edward Burlingame Hill, at one time a respected American symphonist, has just about disappeared from concerts and recordings. This may well be the only CD of his music currently available in the U.S. I like his chamber works best, a genre most suited to his essentially modest and reticent artistic nature. The Prelude for Orchestra opens slowly in a way that reminds us, if nothing else, of musical Impressionism's roots in Wagner. It sounds stuck half-way between Tristan and Debussy's faun. A quicker section reinforces the Impressionism, and from then on it's pretty much à la française to the end. It's very refined writing, but not particularly memorable, except for a pretty magical ending. Much of it goes by, however, like the scenery in southern Illinois before you get to that particular delight.

The big work, in all senses, is the Blitzstein Airborne Symphony. The composer began as a Schoenberg disciple and produced a lovely piano concerto in the dodecaphonic style. However, Blitzstein stood politically on the left, and leftist Thirties aesthetics dictated that art reach out to the common man. Hanns Eisler and Kurt Weill in Germany faced the same problem. They all knew that the common man wouldn't have sat still for their particular brand of High Art. They all solved the problem in the same way: to write in the idiom of popular sources. Since they had gone through a very rigorous training of a certain kind, they weren't going to write exactly popular music, although Weill came close in his Broadway career, achieving a couple of "standards," and Blitzstein had a minor pop success with his song "I Wish It So." However, there's nothing written just for disposable entertainment – like Victor Young's "Sweet Sue," for example – in any of their work. High Art lurks in the back of their minds, even in something as raucous and self-consciously worked-for American as Weill's "Saga of Jenny." In Blitzstein, this stands out more obviously than in Weill's American output. The music sounds like a hodge-podge of "open-prairie" Copland, Broadway pizzazz, neoclassicism, corrosive Eislerian satire, hints of jazz, a little of the Berlin Weill, and something strongly individual. Indeed, the mixture reminds me of – guess who? – Bernstein himself, particularly the Broadway sections. It's what I would normally think of as Bernstein's Broadway, but Blitzstein got there first. The main problem with it, it seems to me, is that Blitzstein had specific political issues he wanted to address: the necessity of defeating Fascism (he began writing the symphony during World War II), and the opening up of a second front – the Normandy invasion finally mounted by the British and Americans. Ironically, the symphony's première took place after the war, when these issues had lost their immediate point. Still, Blitzstein enjoyed a success.

Any "political" artist runs the risk of datedness and quaintness. I don't deny that parts of the "Airborne" call up a very specific time, as does, incidentally, Dickens's Hard Times or Blitzstein's Cradle Will Rock. I can't separate Bernstein's Mass from memories of the Viet Nam War, either. However, I think it a mistake to dismiss political art or political elements in the art as Something That Happened Then. After all, one can still find plenty of political thuggery about without too much trouble. I propose the following corollary to Santayana's dictum of not knowing the past leading to committing the mistakes of the past: we pretty much make the same mistakes whether or not we have studied the past, usually because we consider ourselves smarter than the rubes who came before us. The best political art, although occasioned by specific incidents, often talks about things always with us. I don't say that Blitzstein's symphony is a perfect work. His own text often touches the sappy, in a Norman Corwin-ish way. Bernstein's "Kaddish" symphony suffers for the same reason. However, music takes the curse off a lot of bad poetry, as a good perusal of Brahms' songs will confirm. The music's the thing, and it rises to moments of great power, particularly in the "Ballad of the Cities" movement, about the air war from the perspective of those beneath the bombs. The "Ballad of the Bombardier" – a young flier writes home to his wife – is beautifully simple and touching. And then there's the simple fact of so many memorable tunes in the piece: the aforementioned "Ballad of the Bombardier," "Ballad of History and Mythology," "Ballad of Hurry-Up," to name a few. I've never forgotten the rat-a-tat exhortation to "Open up that second front!" since I first heard it, almost forty years ago. You come out of this symphony, as you do from a wonderful Broadway show – humming the tunes. You can't say that about too many symphonies. Blitzstein wants to connect with a broad audience, and he certainly achieved that goal here.

Bernstein leads a heart-on-the-sleeve performance – in my opinion, the only way to play it. Quite simply, he – like the composer – goes for emotional broke. The embarrassing excess and sentimentality are there, but so are the power and the genuine sentiment. The symphony is also gorgeously played and sung. Orson Welles chews up the scenery in his role as narrator, although the honied burr of his deep voice eventually seduced me. One doesn't hear the word "authenticity" much these days (probably for good reasons), but Blitzstein's cleaving passionately to the truth as he saw it and – let's face it – his artistry ultimately reduce the complaints to mere carping.

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz