The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

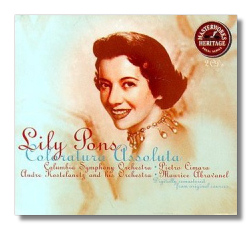

Lily Pons

Coloratura Assoluta

- Alexander Alexandrovich Alyabyev: Salaviei (The Nightingale) 2

- Ambroise Thomas: Mignon - Je suis Titania 3

- André-Ernest-Modeste Gretry: Zémire et Azor - La Fauvette 3

- Charles Gounod: 2

- Mireille - O légère hirondelle

- Roméo et Juliette - Je veux vivre

- Claude Debussy: 5

- Clair de lune "Votre âme est un paysage choisi", L. 32

- Fantoches "Scaramouche et Pulcinella", L. 21

- Darius Milhaud: Chansons de Ronsard #1-4, Op. 223 3

- Gabriel Fauré: Les Roses d'Ispahan in D Major, Op. 39/4 4

- Gaetano Donizetti:

- La fille du régiment - Arias 1

- Linda di Chamounix - O luce di quest'anima 3

- Lucia di Lammermoor - Arias 1

- George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess - Summertime 2

- Giacomo Meyerbeer: Dinorah (Le pardon de Ploërmel) - Ombre légère (Shadow Song) 1

- Giuseppe Verdi:

- La Traviata - Ah, fors'è lui… Sempre libera 2

- Rigoletto - Caro nome 1

- Henri Duparc: L'invitation au voyage (Mon enfant, ma soeur) 3

- Jacques Offenbach: Les contes d'Hoffmann - Les oiseaux dans la charmille 2

- Johann Paul Aegidius Martini: Plaisir d'amour 2

- Johann Strauss II: Die Fledermaus (The Bat) - Fledermaus Fantasy 4

- Léo Delibes: Lakmé - Arias 1

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakoff: 2

- Le Coq d'Or (The Golden Cockerel; Zolotoy petushok) - Hymne au soleil

- Sadko - Song of India

- Henry Rowley Bishop: Clari - Home, Sweet Home! 2

- Vincenzo Bellini: 3

- I Puritani - Son vergin vezzosa

- La sonnambula - Ah, non credea… Ah, non giunge

1 Columbia Opera Orchestra/Pietro Cimara

2 André Kostelanetz Orchestra/André Kostelanetz

3 Columbia Concert, Opera or Symphony Orchestra/André Kostelanetz

4 Metropolitan Opera Orchestra/Maurice de Abravanel

5 Frank La Forge, piano

Sony Classical Masterworks Heritage MH2K60655

In the Forties and Fifties, opera made an earnest attempt to capture American's heart and pocketbook. High-rolling tenors and sopranos performed for burgeoning audiences in remote locations, such as Ipswich, MA. They also appeared on non-PBS television shows, such as The Ed Sullivan Show and Jack Paar's The Tonight Show; in series like Metropolitan Auditions of the Air, Opera Cameos, and Opera Vs. Jazz; and even in complete productions sponsored by the Hallmark Hall of Fame or Omnibus. Works like Mozart's Cosí van Tutti were performed and recorded in English (Women are Like That, 1952, re-released by Sony Classical Masterworks Heritage MH2K60652, 1998).

Then there was Lily Pons.

Few opera stars have led such an impressive career. For over a quarter of a century, her coloratura voice captured the stages of Paris, London, Buenos Aires, Mexico, and the United States. Like Mario Lanza and Luciano Pavarotti, she acted in second-rate films about opera stars, which were surprisingly well-attended. As a child, I recall her appearances on variety shows and heard her on the radio at least once a month. Today, there is a Lilypons, Maryland (and its main street, Lily Pons Rd.). Even a contemporary rock group has named itself after her. She was the Three Tenors of her day.

Her sweet soprano voice had an extremely high tessitura. It was said she could hold a high D for about a minute. The Metropolitan Opera revived roles especially for her, like Delibes' Lakmé, Donizetti's La Fille du Regiment, and Rimsky-Korsakov's Le Coq d'or. All these works are generously represented in Lily Pons, Coloratura Assoluta. At 157 minutes, this may be the definitive edition of Lily Pons. I know of no other. It is splendidly engineered. Virtually all hissing and dropout, the bane (or charm) of 78-rpm recordings, has been eliminated. There are the usual problems with midtone fidelity and less than optimal balance between singer and orchestra, but these are minor flaws. This is an exceptional disk. The music holds up well and Lily Pons' voice emerges with resounding clarity and dazzling reproduction, perhaps better than ever. All the famous show-stoppers are here: the stunning "Mad Song" from Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, with a nine-minute teaser before the coloratura fireworks; "Ombre légère" ("Shadow Song") from Dinorah, with impressive legato phrasing and dizzying flute dialog; and of course "Où va la jeune hindoue" (the "Bell Song") from Lakmé. This signature piece, narrated by Lakmé about a girl protecting Vishnu in a dangerous forest with magic bells, weaves an exotic mood through its ineffable charm. I would have loved to have seen diminutive Lily Pons, costumed as a Hindu, prancing about the stage, striking the bells, singing this scintillating mixture of lyricism, tension, and release.

Pons was not above adapting texts to her own use. Conductors helped her create coloratura cadenzas in arias where there were none. She also changed composers' directives. Rimsky-Korsakov's "Hymne au soleil" (Le Coq d'or) calls for a legato descent toward the end, but Pons sings it staccato, to awe-inspiring effect. Donizetti's "Salut à la France" (La Fille du regiment) omits the chorus, as does Olympia's aria from Offenbach's "Les oiseaux dans la charmille" (Les Contes d'Hoffman). In this last aria, she eliminates the humor. She does not comically "wind down" the voice of mechanical doll Olympia like other coloraturas do, but merely drops the tempo for a second. Ex-husband/conductor André Kostelanetz even omits the sound of the key turning to crank her back up. (I've always thought this aria a wonderful analog of the diva being cranked up by public acclaim.) She doesn't exactly break the rules, but she bends them. Exquisitely.

Sometimes she broke out of the bel canto mold and sang modern lieder. She infuses Henri Duparc's "L'Invitation au voyage," a restrained and unremarkable piece, with her passionate spirit. Debussy's "Clair de lune" is her noble attempt to spin a languid mood, but she is not quite sensuous enough. She is more successful in "Fantoches" and in Milhaud's songs from Chansons de Ronsand, particularly the whimsical "Tais-toi, babillarde." She is vivaciously rhythmical and interprets Milhaud's inventive phrasing, which sometimes borders on dissonance. Unfortunately, these were not her most popular pieces.

Lily Pons, Coloratura Assoluta is a worthy addition to any masterworks collection. Even the inclusion of the schmaltzy "Home Sweet Home" or a curiously inappropriate "Summertime" can't tarnish the sheen of this compilation. They complete it, making us realize that although tastes were different in 1941, some arias are so difficult that their extraordinary execution always demands a standing ovation.

Copyright © 1999, Peter Bates