The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Sculthorpe Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

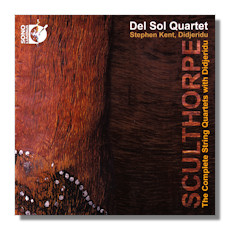

Peter Sculthorpe

Complete String Quartets with Didjeridu

- String Quartet #12 "From Ubirr"

- String Quartet #14 "Quamby"

- String Quartet #16

- String Quartet #18

Stephen Kent, didjeridu

Del Sol String Quartet

Sono Luminus CD+Blu-ray Audio DSL-92181 2CDs+Blu-ray

Peter Sculthorpe was born in 1929 and died in August of this year (2014). The leading Australian composer of his generation, he drew inspiration both from the wildness and wildernesses of Australasia (he was born in Tasmania) and the native cultures of the region. Of the total of 18 string quartets numbers 12, 14, 16 and 18 additionally have the traditional Australian wind instrument, the didjeridu. Also spelt "didjeridoo", modern versions are usually around four feet long – but can be as long as ten feet… the longer the pipe the lower the pitch. It's thought that the didjeridu was developed by (indigenous) Australians 1,000 to 1,500 years ago.

The addition of instruments to the string quartet other than the expected second viola or cello, piano, clarinet, flute or even electronics to what is such a "pure" combination of stringed instruments can be as much an intrusion as a pleasure. This is not the case here. Although Sculthorpe includes musical effects such as wind, animal and other natural sounds, they are invariably welcome and successful. In fact in such passages as the (end of) "Trauma", the fourth movement of Quartet 16 [CD.2 tr.4], the strings too work to express birdsong. Throughout the "Prelude" first movement of number 18 [CD.2 tr.6], they bring insects to mind. An environmentalist, the composer had a thoroughly and rounded conception of the role of music and the Earth in our lives. But the didjeridu acts chiefly as a musical, melodic and harmonic component in the compositions.

So this two-CD set from the enterprising Sono Luminus is no "New Age" novelty, or would-be "mood" music. It's thoughtful and carefully-written music where the didjeridu not so much extends the range and textures of the string quartet (though it certainly does that at times) as supports its deeper resonances. It adds tones of melancholy and reflection which form such an intimate part of Sculthorpe's world view. The 16th quartet was partly inspired by the plight of asylum seekers in detention centers in Australia, for instance. The others clearly reflect Sculthorpe's concern for the plight of our world. In an interview in the Australian music magazine, "Limelight" in 2009 he said that his work has been about "…the preservation of the environment and more recently, climate change".

Significantly, both the Del Sol Quartet and didjeridu player, Stephen Kent, have great sensitivity to the sound world which Sculthorpe creates. They are also alive to the variety which the didjeridu and string quartet are capable of. The quartets may remind you of Shostakovich for their melancholy, their bite (which is never so unflinching as in the quartets of Shostakovich) and the way in which they combine expansive structures with a very personal (yet accessible and not self-indulgent) melancholy. Where Shostakovich alluded to urban gloom and spite, Sculthorpe conjures up a fragile natural world barely clinging to its beauty.

This is not, though, music that paints. It's certainly figurative at times with those bird sounds and the ferocity of nature. But the Del Sols are not helping Sculthorpe make a point. They are making music. And Stephen Kent (actually British, who lived in East Africa, also a composer and multi-instrumentalist trained on the French horn) plays the didjeridu with sensitivity, light and enthusiasm; yet actively and in an appropriately respectful way – for this must not be how the native Australians who first used it could have imagined it would ever sound.

For the most part these string quartets are laments; they're slow; they have lingering, ruminative qualities – rather than, say, a Haydnesque jollity. Although there are moments obviously inspired by "folk" traditions and music… the second movement ("A Land Singing") of the last (18th) Quartet, for example [CD.2 tr.7]. Again, the Del Sol Quartet and Kent play the music as music, rather than try to erect a (spurious) "experience" emanating from the non-standard instrumental combination and intensity of Sculthorpe's writing.

In the long run – if not even on first hearing – this richness is what the listener will want. If for no other reason than that Sculthorpe is reflective regardless of his instrumentation. Perhaps the greatest compliment which one can offer for these performances is that the didjeridu appears so transparently in the music – just as Sculthorpe successfully integrated the sound world of the gamelan into his Eighth String Quartet in 1969. Yet it adds to their musical impact. When you first encounter it in the otherwise relatively traditional treatment of a group of strings, the didjeridu stands out. By the end of your first listening, it seems natural.

If these performances have a single aggregated virtue over others, it is that they are evidence of a holistic approach: the richness of the harmonies, the sense of unfolding melodies, the gentle exploration of complex textures all take precedence over what for most listeners will be unusual and even mildly experimental. That Sculthorpe has something valuable to say is never in doubt. And this is how to say it without fuss, platitude or self-consciousness.

Sono Luminus is a label that prides itself on the sound quality of its releases. These two CDs and one Blu-ray are no exception. The recordings were all made at the label's studio(s). The sound is excellent: warm, close and compelling; though the acoustic leaves enough space for the music to expand and move when it needs to. The booklet has background on Sculthorpe, and well-written commentaries on each of the quartets; particularly useful are the explanations of the relationships between the composer, the parts of the country in which he worked, and the sense in which Australia is a metaphor for the plight of the planet. On Tall Poppies 206 the Goldner String Quartet has recordings of Sculthorpe's quartets 14, 15, 16, 17, though without didjeridu. Good though those recordings are, the present set must be regarded as the one to go for. If you know, like or are just beginning to explore the extraordinary world of Peter Sculthorpe, this is an excellent place to start.

Copyright © 2014, Mark Sealey