The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- J.S. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

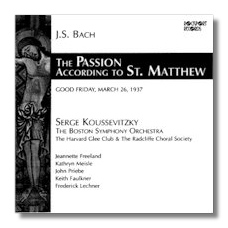

Johann Sebastian Bach

St. Matthew Passion

Jeannette Freeland, soprano

Kathryn Meisle, contralto

John Priebe, tenor/Evangelist

Keith Faulkner, bass/Jesus

Frederick Lechner, bass

Harvard Glee Club

Radcliffe Choral Society

Boston Symphony Orchestra/Serge Koussevitzky

Rockport Records RR5012/4 A?D monaural 3CDs: 61:03, 70:22, 61:07

RCA Victor took its risks when it recorded Bach's towering St. Matthew Passion on March 26 (Good Friday), 1937. The conductor was Serge Koussevitzky, a man certainly admired for his work with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, particularly in contemporary Russian music, but hardly a Baroque scholar. (It is unlikely he knew the entire work – or much of Bach performance tradition in general – prior to preparing this recording.) The recording was done "live," which presented challenges in audience and stage noise, and in managing side breaks. (Remember that the average 78rpm side could hold between four and five minutes of music.) The work was presented practically note complete, an achievement not matched even in European recordings conducted by Mengelberg and Weisbach. The result was well over three hours of music. RCA Victor released the shellac discs in three multi-record sets whose combined weight must have been similar to that of a well-fed beagle. How many people could afford it in 1937? Outside of libraries, these records must have been inaccessible to the average music-lover.

Koussevitzky, like his disciple Leonard Bernstein, makes the music accessible, even if the records weren't. One is immediately struck by the emotive power of this performance, the charged atmosphere that tells you that something historic is happening. Free from academic prejudices, Koussevitzky follows his instincts and creates a St. Matthew Passion that is non-traditional (at least by today's standards), yet dramatic and devout. Time seems to stand still in the chorales, which are sung by the Harvard and Radcliffe groups with an honesty that precludes boredom and concerns about stylistic refinement. Koussevitzky also favors slow tempos in some of the arias, but again, what he and his soloists do is often so lovely that one does not become impatient. Elsewhere, he moves the action along tautly, emphasizing the Passion's drama.

None of the soloists are big names today. Soprano Jeannette Vreeland tends to scoop between her notes, yet, in her defense, this was a stylistic quirk that had not completely died by 1937. (You can hear the Orchestra's strings using more generous portamento here than they would even in the day of Charles Munch.) Her somewhat disembodied tone does pay coloristic dividends in this music. Alto Kathryn Meisle is dependable but seldom memorable. As the Evangelist, tenor John Priebe is initially detached, but as the work progresses his voice rings, and his involvement becomes clear. (The tenor solos also go to Priebe, this being an economical performance.) Bass Keith Faulkner's Jesus rarely has the charisma that one wants in this work. Nevertheless, he sings well. For me, the star soloist is bass Frederick Lechner, who was making his U.S. debut at this concert. He had recently left Germany to escape religious persecution; in time, he became cantor at the Central Synagogue in New York City. Lechner is bitingly dramatic, and his characterful voice cuts through 60-plus years of surface noise and other sonic limitations. Koussevitzky also was of Jewish origin, and Rockport's notes indicate, without naming names, that the concert included several other "recent refugees from Nazi persecution and a number of other immigrants whom the Nazis would have pursued, given the chance." Lechner's presence also reminds me to mention that this performance – like the ones that Bernstein would give more than two decades later – is in English, a practice I suspect that Bach would not have deplored. It is odd, yet moving, to hear Lechner singing the English translations of German texts with a thick German accent. Then again, just about everything about this recording is moving.

Somehow, the balance between choirs, vocal and instrumental soloists, and the orchestra is handled well – the choir does blast on a very few occasions. The organ, played here by the young Carl Weinrich, is rather prominent. The side-breaks, also with a few exceptions, turned out well, and John Wilton's excellent transfers minimize the seams. Rockport includes an essay by Tully Potter and the English texts. The presentation is a bit on the minimalist side, but no matter.

This is one of those few historic recordings that deserve that epithet. It's not "authentic" Bach, but it's wonderfully moving and atmospheric.

Copyright © 2000, Raymond Tuttle