The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

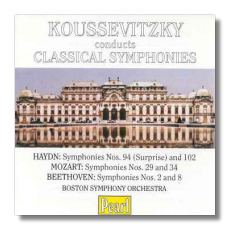

Koussevitzky Conducts

Classical Symphonies

- Franz Joseph Haydn:

- Symphony #94 in G Major "Surprise"

- Symphony #102 in B Flat Major

- Wolfgang Mozart:

- Symphony #29 in A Major, K. 201

- Symphony #34 in C Major, K. 338

- Ludwig van Beethoven:

- Symphony #2 in D Major, Op. 36

- Symphony #8 in F Major, Op. 93

Boston Symphony Orchestra/Serge Koussevitzky

Pearl GEMMCDS9185 AAD monaural 2CDs 64:19, 73:25

Serge Koussevitzky was a strong and insightful supporter of new music, but he had important things to say in the Classical repertoire as well, as this new set shows. Another Mark Obert-Thorn production, it contains six recordings. The earliest (Haydn's "Surprise") was recorded in 1929, and the latest (Mozart's Symphony #34) was recorded in 1940. All of these recordings originally were issued on the Victor and HMV labels.

In the words of Robert Layton, who wrote the introduction to this set, "in the classical repertoire, Koussevitzky cannot always be called totally unmannered yet his is an outsize personality, and the virtuosity of his wonderful players is always worn lightly." I concur, even when the conductor is encouraging emphatic accents or cutting remarks from the brass, and engaging in tempos that don't seem quite authentic. An example of the latter can be heard in the opening movement of Mozart's Symphony #29. Koussevitzky's approach is anything but relaxed and cordial, but the tension that he creates is so invigorating that we can't help but admire the result, even if it's wrong-headed. Toscanini, another tense conductor in the classical repertoire, frequently was unable to leaven the tension with charm, and that's why I prefer Koussevitzky's Haydn and early Mozart to Toscanini's. As for the Russian-born conductor's Beethoven, the Eighth is virile, knock-about fun, and while the Second doesn't quite reach the level of the other recordings on this set, it's still a major interpretation. And what a great-sounding orchestra the Boston Symphony Orchestra was in the decades around World War II!

Collectors with less intrinsic interest in historical recordings might care to sample this set to see where Leonard Bernstein's admirable Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven came from. As his career progressed, Lenny sounded less and less like his mentor Koussevitzky, but even his New York Philharmonic LPs of this repertoire show that his student years were spent with ears wide open. (Dimitri Mitropoulos's influence can also be heard in Bernstein's earlier work.)

As usual, transfers have been done with great sensitivity, and the surface noise is not disturbing. Obert-Thorn has included two takes of the "Surprise" Symphony's final movement: the third take is the one that was originally issued, but, because of distortion, it was replaced with the noisier first take in the 40s. Like an audience-participation movie, Pearl lets you decide which take you prefer. I like the original one better. So must Obert-Thorn, because that's the one that comes first.

Copyright © 1996, Raymond Tuttle