The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

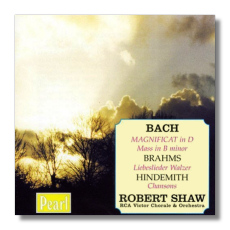

Classic Shaw

- Johann Sebastian Bach:

- Magnificat in D Major

- Mass in B minor: Laudamus te; Benedictus

- Johannes Brahms: Liebeslieder Walzer, Op. 52

- Paul Hindemith: Six Chansons

RCA Victor Chorale and Orchestra/Robert Shaw

Pierre Luboschutz and Genia Nemenoff, duo-pianists

Pearl GEM0180 ADD monaural 66:40

For more than a half-century, Robert Shaw was synonymous with classical choral singing in the United States. He began with a college glee club and a fairy-tale discovery by Fred Waring, and continued with praise from no less than Arturo Toscanini, who asked Shaw to direct the chorus in a performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Later, he formed the Robert Shaw Chorale, made what seemed like a hundred records for RCA Victor, and moved on to orchestral engagements in San Diego, Cleveland, and finally Atlanta. When he died in 1999 (at the age of 82), he was still recording the essential choral literature – now in spectacular digital sound – with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus for the Telarc label.

The present recordings were made between 1945 and 1947, shortly before Shaw formed his eponymous Chorale. The high standards and excellent musicianship of later ensembles are fully evident here, however. The RCA Victor Chorale sings with superb discipline and crispness, and with an immediacy that must have seemed shocking at the time. (The first half of the Twentieth Century was not a golden era for choral singing.) Diction is clear but not exaggerated, and communication with the listener is always the uppermost goal.

Having said that, the massive Magnificat will sound quaint to modern ears accustomed to John Eliot Gardiner and the like. In 1947, there was no authentic performance movement to speak of, although I think it is a little much (pace Roger Thomas's booklet note) to compare Shaw to Stokowski. While Shaw wanted good music to be popular, he had more faith in the average listener than Stokowski, who always searched for ways to popularize good music, which is not at all the same thing! Anyway, this Magnificat is Big Bach with a vengeance; no false modesty here. The interpretation and the singing, while they are flying mallet-like in their subtlety, are heard to resist because of the enthusiasm expressed and the technical skill displayed. The soloists are a mixed bag – the tenor is a stylistic horror, but then again, we do have the pleasure of hearing mezzo-soprano Blanche Thebom. The trumpeter is the great William Vacchiano, whose name is repeatedly misspelled "Vacciano." Speaking of instrumental soloists, violinist Oscar Shumsky appears in two selections from the B-Minor Mass, recorded two years earlier. I don't suppose Pearl intends to reissue the entire recording (all 34 shellac sides of it!), and that's a shame, but I like these two souvenirs, and the obscure soloists (soprano June Gardner and tenor Lucius Metz) don't disgrace themselves, even by today's standards. (You need to have high tolerance for "Bay-nay-deek-toos kwee vay-neet"-style Latin, though.)

With Brahms, Shaw is on firm ground, and these Liebeslieder Waltzes (recorded in 1946) are simple and unaffected, just as I imagine Brahms would have wanted them to be. The only complaint I have is that some of the numbers are too fast ("Vögelein durchrausscht," for example), but I blame that on RCA's presumed desire to fit more waltzes on a side. Perhaps Hindemith's six Rilke Chansons bring out the best of all from Shaw and his musicians, and this was adventurous indeed in 1945. They make an odd postlude to Bach and Brahms, however.

The excellent transfers are by Roger Beardsley, who is not afraid to leave in a little surface noise so as not to filter out the music itself. The sound in the Brahms and Hindemith works is oppressively dry (were they recorded in the infamous Studio 8-H?); the Bach is more spacious.

Copyright © 2002, Raymond Tuttle