The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

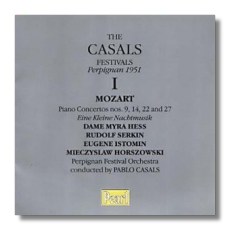

The Casals Festivals – Perpignan 1951

Volume I – Mozart Piano Concertos

- Concerto for Piano #9 in E Flat, K. 271

- Concerto for Piano #22 in E Flat, K. 482

- Concerto for Piano #14 in E Flat, K. 449

- Concerto for Piano #27 in B Flat Major, K. 595

- Serenade "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik," K. 525

Dame Myra Hess, piano

Rudolf Serkin, piano

Eugene Istomin, piano

Mieczysław Horszowski, piano

Perpignan Festival Orchestra/Pablo Casals

Pearl GEMS0167 ADD monaural 2CDs: 73:42, 74:59

Spanish cellist Pablo Casals ceased performing in 1946 to protest the world's indifference to the oppressive Franco regime then in power in his homeland. The silence of the cellist, then in his 70s, was keenly felt by the millions who loved him. When he returned to concertizing in 1950, at first it was only to honor Bach, who had died two hundred years before. Violinist Alexander Schneider (of the Budapest Quartet) was integral in coaxing Casals out of his silence and in planning what became known as the Prades Bach Festival. (Prades was a Catalan village just on the French side of the French-Spanish border, and Casals's erstwhile home.) Next year, the festival moved to Perpignan, took on the cellist-conductor's name, and added Mozart and Beethoven to the mix. Casals had conducted before, but it was at these Festivals that he became a sort of spiritual leader among leaders, and also a musician's musician.

Columbia Records became associated with the Casals Festivals; the label recorded the performances included here "in the courtyard of the Palace of the Kings of Majorca" during the Festival in July 1951. Originally they were released on four LPs, and these have become highly collectible in the interim. Pearl has done us a great service by transferring them to CD, and three more volumes have been planned.

Few people would argue that Casals's baton technique was highly polished, or that he was a "great" conductor in the usual sense. What makes so many of his recordings memorable is his dedication to the music, the care he took in preparing performances (balance, tempo, and exactitude of rhythms were especially important to him), and the musicians themselves. When Casals conducted a festival orchestra (be it in Prades, Perpignan, or Marlboro), it often included many stars and stars-to-be. For example, these 1951 recordings include cellist Paul Tortelier, flautist John Wummer, and oboist Marcel Tabuteau in the orchestra.

This Pearl release allows us to compare and contrast four great Mozartean pianists. In Concerto #9, Dame Myra Hess reveals how strength can be pretty. She is effervescent in the outer movements and full of pathos (but not wilting) in the Andantino, and her "dialogues" with the orchestra are both intimate and spirited. Rudolf Serkin's account of Concerto #22 is extraverted but not shallow. More forward-looking than Hess, he allows himself expressive effects that are achieved through variations in tone and phrasing. The performance is more symphonic than chamber music-like. In Concerto #14, Serkin's pupil Eugene Istomin shares his mentor's red-blooded outlook on Mozart, and he relishes every opportunity for drama. Horszowski's performance of Concerto #27 caps this collection. He and Casals were long-time collaborators. (He also taught Istomin.) As if in recognition of their previous partnerships, they tease each other, musically speaking; Horszowski establishes a classical tone, and Casals seems almost to mock it, but well within the boundaries of what is stylistically appropriate. In so doing, they highlight the one of the great Mozartean paradoxes: how can music that seems so carefree move us so deeply?

The Eine Kleine Nachtmusik that closes the second disc is a nice bonus, but it doesn't seem as finely shaped as any of the concerto performances. As the discs are well filled, I'm not going to complain too hard. However, I do think it was a miscalculation for Pearl to program three piano concertos in E Flat Major back to back. I needed to take a breather after each concerto.

The excellent transfers are by Roger Beardsley, the set's producer, and the source material sounds to have been in good shape. I am looking forward to Volume II (to be released shortly), and to other transfers of material from early LPs, as copyright law permits.

Copyright © 2002, Raymond Tuttle