The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Chopin Reviews

Buxtehude Reviews

Mendelssohn Reviews

Prokofieff Reviews

Rachmaninoff Reviews

Ravel Reviews

Schumann Reviews

Scriabin Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

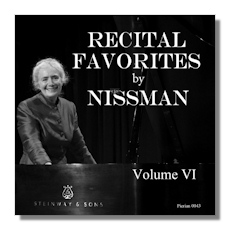

Recital Favorites

Volume 6

- Frédéric Chopin: Ballade #1 in G minor, Op. 23

- Maurice Ravel: Gaspard de la nuit

- Dietrich Buxtehude: Prelude & Fugue in D minor (arr. Prokofieff)

- Serge Prokofieff: Old Grandmother's Tales, Op. 31

- Alexander Scriabin: Sonata #5, Op. 53

- Felix Mendelssohn: Etude in F Major, Op. 104b #2

- Robert Schumann: Piano Sonata #2 in G minor, Op. 22

- Sergei Rachmaninoff: Prelude, Op. 23 #10

Barbara Nissman, piano

Pierian 43 75:40

Summary for the Busy Executive: Yet another winner.

I've passed the midpoint of Barbara Nissman's 10-disc series of recitals, so far an amazing traversal of many of the monuments of the solo piano literature. Nissman's intelligence, ardor, and versatility all recommend themselves to a listener. She tends to pack her discs with a lot of red meat. Even her encores are either substantial or unusual. She doesn't seem to go for fluff. In such matters, this CD doesn't differ from its predecessors.

I imprinted on Horowitz's performance of the Chopin Ballade #1. Apparently, many others have as well, since the critics I read usually throw other pianists up to Horowitz for this work. All four Ballades sit comfortably among my favorite Chopins, and consequently I've heard a large number of pianists. Aside from Horowitz, I like (among the older performers) Bolet, Moravec, Anda, Hofmann, and Cortot (clams and all). Among the newer, Argerich, Zimerman, and Biret stand out. All of these folks take the same general approach, and I admit to moments I mentally check off in judging a performance – a I-iii progression (for those of you keeping score; roughly a C chord followed by an e-minor) at the end of the big singing theme, the swing of the song theme, and the finale. Nissman points out in her notes that Chopin doesn't really do development. He varies instead. He mostly varies the opening "Chopin turn" at the beginning of the first real theme – minor to major, and even just the rhythm of the thing. Contrasting episodes appear between the appearance of that theme. Apparently, Chopin based his ballades on literary ballad poetry. According to Wikipedia, Ballade #1 was inspired by Adam Mickiewicz's Konrad Wallenrod. In any case, you don't need to know the poem (which, by the way, ends with the suicide of the hero) in order to follow the music, but you might guess the general mood, if you did know the poem. I have praised Nissman's Chopin in the past, but she doesn't set any of her interpretations in stone. She seems to prepare tremendously and then surrender to the moment. Usually, the risks pay off. There's much to admire in her Ballade. For one thing, it's one of the most cohesive accounts I've heard. You not only can follow the twists and turns of Chopin's way with his themes, but she hits all the points I listen for. Her song theme has ardor without soupiness. Her quick passages allow you to hear Chopin's "piano counterpoint." In her hands, the piece doesn't break apart into sections, but one hears the work as an entity. Nevertheless, for this piece, in the words of Mae West, "I like a man what takes his time." Her approach is too elegant for me. Someone like Zimerman risks going off the edge or dissolving into incoherence, so intently does he strive to fill the piece with Magic Moments. Nissman does well without, for me, achieving the magic. The opening, for one, isn't "lonely" enough, compared to Horowitz, Zimerman, Argerich, or Moravec. Undoubtedly, she delivers a fine account, but Horowitz is safe.

In his piano spectacular, Islamey, Balakirev had striven to write the hardest piano work in the repertoire. Scriabin, it's said, injured his right hand practicing it. In Gaspard de la nuit, Ravel aimed to out-Islamey Islamey. I've heard Ravel play on Welte-Mignon piano rolls (you can, too, on Pierian 13). Indeed, if I had kept up with lessons and practice, I would have played nearly as well (i.e., not very). He couldn't have made a living as a recital pianist, but he understood piano writing like nobody's business, as he invents one ravishing texture after another.

The considerable difficulties of the score don't necessarily fall into the finger-busting category. A pianist friend of mine who had sailed through Messiaën's workout, Catalogue d' oiseaux, had fits with the pianissimo opening of Gaspard's final movement, "Scarbo" – getting very quiet, fast repeated notes to sound without raising the volume. I've heard the work from various pianists, including Robert Casadesus and Walter Gieseking. The most inspired performance I've heard came from Samson François. Many pianists make the mistake of trying to get through the piece as fast as possible, as if it were nothing beyond a display of virtuosity. Ravel takes off, I think, from the Lisztian literary character-piece (it's based on three poems by Aloysius Bertrand), and those scores demand not only fingers, but poetry. As in a piece like Liszt's Mephisto Waltz #1, so here. Each of Ravel's movements has a strong programmatic element (although you needn't know the program) and challenges the player to find each individual "narrative."

Gaspard falls into three parts: "Ondine," "Le gibet," and "Scarbo." "Ondine," kin to the Lorelei, tries to lure men to her watery home and their deaths. Water-effects fill the movement. At the climax of the poem, where the mortal rejects the sprite, Ondine screams and disappears. You can hear in the music her scream explode and dissolve into what sounds to me like sea spray.

"Le gibet" for me counts as the most radically conceived movement. The poem depicts bells tolling as the corpse of a hanged man sways on a scaffold. The bells toll throughout the piece, and a B-flat, representing those church bells, repeats over 150 times throughout all the piano's registers. Ravel risks and brilliantly avoids harmonic limitation. The chord progressions are unusual and the B-flats as dissonance perfectly placed. The pianist must keep this essentially slow and static scene musically moving along.

"Scarbo," the most overtly virtuosic with lots of hand-crossings, complex textures, and fast repeated notes, paints a picture of a mischievous goblin. As I say, the piece tempts virtuosi into showing how quickly they can bring all this off, at the expense of its considerable musical virtues. Argerich, for example, falls into this trap, although she certainly captures the macabre aspects of the piece.

Since I'm no pianist, I can't say much about Nissman's technique compared to others'. However, her reading satisfies me like few others. For one thing, she not only holds "Le gibet" together, she makes you see the hanged man swaying in the wind. There's a similar visual effect in "Ondine." Her "Scarbo" capers and grimaces as much as Argerich's, but she also "tells the tale." Furthermore, her tempo is not so fast as to obliterate the connections to Ravel's "Spanish" mode, in works like the "Alborado del gracioso." It reminds me of Alicia de Larrocha's reading. All in all, a marvelous Gaspard.

Prokofieff the composer has almost completely overshadowed Prokofieff the pianist. Yet his contemporaries hailed him as one of the greats. Poulenc, for example, called him "the Russian Liszt." The Buxtehude arrangement comes from 1918, during a tour of the United States. Almost certainly, he wrote it as an encore or a filler for his recitals. Nissman points out that Prokofieff leaves out the difficult parts of the original. Since this couldn't have come from deficiencies in Prokofieff's technique, she speculates the omission reflected his dim opinion of American audiences, and he certainly had reason on his side. Old Grandmother's Tales, written around the same time, consists of four wonderful miniatures. The themes, absolutely beautiful and mainly in the composer's Russian folk vein, make a strong case for Prokofieff as one of the great melodists of the century. Nissman has tremendous Prokofieff cred, and her individual readings stand with anyone you care to mention. Her integral sonata cycle I consider the best out there. Here, the music demands less from the player, but she doesn't slough anything off. Indeed, she nearly transforms the piano into a human singer.

Many consider Scriabin's Sonata #5 his first completely characteristic piece. I see the point, but I've always felt that it shares much with the Sonata #4. Nevertheless, it does proceed structurally in a new way. Scriabin builds the entire sonata both on a single motive and on a characteristic harmony – one that to me presages the construction of his so-called "synthetic chords." There's a bit of Debussy in here as well. Rhetorically, the piece flows back and forth between oriental yearning and ecstatic dance. Languor coalesces into dance which melts back into languor. Nissman makes these transitions seamless. Again, the coherence of her account makes a deep impression. After all, this music could dissolve into goo. Furthermore, unlike many, she never indulges in or ratchets up to hysteria. The ecstasy remains pure joy. Taneyev, Scriabin's counterpoint teacher, commented to the composer, "I feel as if I've been beaten with sticks." Considering one of the sub-themes (sharply rapped-out chords), I can sympathize, though not entirely agree. Scriabin brings off a bizarre ending, so sudden it's as if you watched somebody disappear down a ha-ha.

Few people know Mendelssohn's solo piano music, excepting the Songs Without Words, but here and there one runs across gems like the 6 Preludes and Fugues from mainly the mid-1830s. The 3 Etudes also appear around this time, but were published posthumously in 1868. I have no idea what the other two are like, and I would like to hear them to understand how this one in F functions within the group. The piece shows piano smarts and a beautifully clear narrative. Although one can't claim for this the depth of a Chopin or Debussy etude, it's an attractive little work, full of quick runs in the right hand, larger-than-usual leaps in the left, and a skeletal middle – a lot like "The Bee's Wedding" from the Songs Without Words. Under Nissman's fingers, it refreshes like a cold glass of really good water.

I wish I liked Schumann's piano sonatas, but I don't. They seem clunky to me, the second more than the first. Even the piano writing of #2 has little of the sonority of, say, the Fantasy in C. Schumann wrote it to show off wife (or maybe wife-to-be) Clara's virtuosity, so there are "a lot of notes played very fast." Schumann marks the first movement "as fast as possible" and then asks for faster once the movement begins. I think you can take that initial marking with a grain of salt. Furthermore, the fast tempo tends to make the sonority even tinnier. Argerich is my benchmark for this movement. She actually gets me to like it. The sonata structure seems pro forma. Compare this to even a middle Beethoven sonata, and you recognize immediately the sketchiness of Schumann's argument. Of course, not everybody has to be Beethoven (not everybody can be, for that matter). Yet even on its own terms, it seems to need a great interpreter to come off. Many great pianists crash and burn with this one. Whatever pleasures the movement provides don't come from its architecture. It's crabbed and cramped. It lacks "space." Actually, Nissman does quite a bit to fill in its lacks. She sings and phrases like Pinza. She gives it the heft it needs, mostly by ignoring Schumann's tempo markings. She pays attention to the arresting detail. I think especially of the sudden fanfares in the exposition, a detail that often gets lost.

The slow movement, my favorite, comes from Schumann's 1828 song "Im Herbste." The title means "in Autumn," just to give you an idea of the general mood. The movement allows Schumann to sing his head off, one of the things he does best. As Tovey once remarked, like the best of Schumann, it is "recklessly pretty." I wish I could adequately convey Nissman's ability to make the piano sing. It's the key to her magnificent Chopin, Liszt, and Rachmaninoff. It's never over-the-top or swooningly sentimental. I might call it "chaste," if that word didn't imply "passionless," which it certainly is not. It puts me in mind of Hofmannsthal's Marschalin – patrician, clear-eyed.

A brief scherzo follows. This seems the movement most characteristic of the composer, reminiscent of the Davidsbündlertänze, Carnaval, Faschingsschwank aus Wien, and even Kinderszenen. It's a burst of fire and over in a moment – Florestan in eruption.

Schumann wrote another version of the finale, by all accounts a very interesting piece (I've never heard it), but Clara made him change it on the grounds that it was too far out for the audience. Many have called the rondo he substituted tame, but I don't find it so, probably because I don't know the original. To me, it's a poetic blaze. Again, the structure, if we judge by classical principles, seems a little bald, particularly in the alternation of aggressive and lyrical episodes. On the other hand, Schumann considerably develops the stormy main theme. The lyric episodes act mainly as "breathers," windups to yet another release of manic energy. Perhaps I don't dislike the sonata as much as I had thought. On the other hand, Nissman goes a long way toward persuading me.

We end the recital on a Rachmaninoff prelude, not one of the two famous ones. To me, Rachmaninoff's solo piano music can often just go by. The, Op. 23 #10 prelude, a gorgeous Chopinesque nocturne, unfortunately often does. I've heard mainly Russians plus Alexis Weissenberg play this. The Russians tend to ham it up. Ashkenazy, however, steps up to the line without stepping over. He seems able to channel this composer. Stephen Osborne, another favorite, plays it fairly straight, but with real feeling. Again, Nissman sings beautifully, without lurching and rolling her eyes to invoke heaven. She focuses firmly on the composer, rather than on herself. She belongs in Ashkenazy's and Osborne's class. All of them make Rachmaninoff sound straightforward, which he certainly is not. There's a lot of hidden art here.

So Nissman gives us fine accounts of Chopin and Rachmaninoff, delights us in Prokofieff and Mendelssohn, and opens up eyes in Ravel and Schumann. I wonder what she'll do next? I can't wait.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz