The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Lopatnikoff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

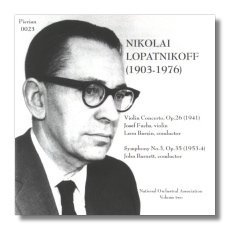

Nicolas Lopatnikoff

- Violin Concerto, Op. 26 (1941) 22:13 *

- Symphony #3, Op. 35 (1953-4) 30:16

* Joseph Fuchs, violin

* National Orchestral Association/Leon Barzin

National Orchestral Association/John Barnett

Pierian 23 2004

The music and very name of Nicolai Lopatnikoff (1903-1976) is hardly known at the present time, but for most of his career he was quite successful. His orchestral music was performed by many eminent conductors (as well as some less well known), including Ansermet, Bernstein, Doráti, Koussevitzky, Krups, Munch, Ormandy, Paray, Reiner, Rodzinski, Steinberg, Stokowski, and Walter. He received major commissions, awards and honors, the latter including two Guggenheims, and membership in the National Institute of Arts and letters., as well as some European awards. He was born in what is now Tallinn, Estonia. He studied in St. Petersburg, Helsinki and several places in Germany, where he began to be established as a composer. He left Germany in 1933 for England, emigrated to the U.S. at the beginning of WWII, and became a U.S. citizen in 1944. He taught in the New York area and then in Pittsburg, at what is now Carnegie Mellon.

In Baker's Biographical Dictionary of musicians, 8th edition, Nicolas Slonimsky calls Lopatnikoff an "outstanding" composer and says of his style that "his music is cast in a neo-Classical manner, distinguished by a vigorous rhythmic pulse, a clear melodic line, and a wholesome harmonic investment." I am going to be quoting some reviews of this long-neglected music from the times of these works' premieres, because they were strikingly favorable at a time when neoclassical music of this sort was not always so positively received.

Lopatnikoff's Violin Concerto, Op. 26, was premiered by the Boston Symphony, On April 17, 1942, with Koussevitsky conducting and Richard Burgin, soloist. Hugo Leichtentritt, in Serge Koussevitzky. The Boston Symphony Orchestra and the New American Music (ISBN-10: 1258143437, ISBN-13: 978-1258143435), called it "a vigorous, bold work in the modern contrapuntal, linear style, revealing the composer's uncommon power of thematic invention as well as considerable constructive skill." Three performances in 1945 included the one recorded here, live – Josef Fuchs with the National Orchestral Association, Leon Barzin conducting, on March 12. The Fuchs/Barzin performance was reviewed by Olin Downes, in The New York Times, who found the concerto "very difficult [requiring] eloquence as well as technique…modern in texture [and] eclectic in style, but the idiom is integrated and the instrumentation adds to the effect." He liked the first movement best, finding the finale "forced and episodic," despite "all its rhythmic and harmonic ingenuity." He did find virtuosity in the composition as well as in the playing. (The other performances that year were Fuchs with the NBC Symphony conducted by Frank Black, June 3; and the New York Philharmonic under Artur Rodzinski, October 27.)

Considering the age of this historic recording of the Violin concerto, the sound is adequate enough to appreciate the work, especially the solo part; the violin comes through well--better than the orchestra. The work begins with some attention-getting thumps and trills; the violin's entrance is lively and the soloist continues at a very fast pace. There are some slower, lyrical passages and the full orchestra has an opportunity to sound out for an extended passage before the cadenza and afterwards. The beautiful Andante movement (the longest of the three) features quiet, long melodic lines that are lyrical in the fullest sense of songful. The gentle counterpoint is unobtrusive, but the sounds of a clarinet at the beginning and a horn later are welcome. There is no percussion or loud brass. A single inoffensive cough brings us into the concert hall. The lively finale (which, unlike Downes, I prefer to the opening movement) begins without pause with a saucy, skipping theme. In this Allegro con brio, ma non troppo movement, the skillful orchestration (lighter than in the opening movement) includes percussion (timpani) and some trumpet and trombone sounds but the violin is never upstaged, to use a theatre term. There is a passage that may strike one as mock-solemn, and another, brief quiet one for bassoon and timpani. The ending of both outer movements is conventional and some applause is recorded.

Lopatnikoff's Third Symphony was first performed in Pittsburgh, December 10, 1954, with William Steinberg conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony. Five years later saw the New York premiere, on January 26, 1960, John Barnett conducting the National Orchestral Association. The latter performance was broadcast and recorded with assistance from the International Music Fund. That recording is the one reissued here. Ross Parmenter, reviewing the concert in The New York Times the next day, said the work has strong construction, rhythmic vigor and is "often very appealing, especially the short slow movement, which is placed third [and] is appealing throughout." In the other movements he found "unexpected sections of lyricism, though all three of them are sturdy and animated allegros."

To my ears, the opening, marked Allegro risoluto, is quite fierce – and definitely resolute and assertive as promised. The orchestration allows the woodwinds and brass to stand out; the higher legato strings are nicely supported by the basses. The second movement, Allegro molto is not misnamed either. It is fast, furious, vigorous and sometimes percussive, including action by a snare drum. But there is also some quieter music for the cellos, a muted trumpet and some quietude after a horn call. Some final fierceness yields to a quiet end of the movement. The following Andante opens with legato playing by the high strings, with some nice passages for flute, horns and mixed woodwinds. The full orchestra with plenty of percussion and brass sounds loudly in the finale, Allegro molto again. The pace and mood is varied – fast and furious, solemn and quiet, a tread that is perhaps funereal. A quiet passage featuring all the woodwinds is terminated with a loud drum. Legato strings play loudly but yield to a softer dynamic. After a lovely, quiet concluding passage, a loud two-note thump ends the work.

These works, especially the concerto, need to be revived and I recommended this recording.

Copyright © 2012, James Tobin