The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Granados Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

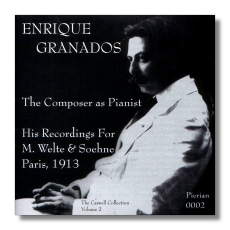

Enrique Granados

The Composer as Pianist

His Recordings for M. Welte & Soehne Paris, 1913

- Goyescas (excerpts)

- Danzas españolas (excerpts)

- Valses poéticos

- Domenico Scarlatti:

- Sonata #9 in B Flat Major, "freely transcribed" by Enrique Granados (Welte-Mignon)

- Sonata #9 in B Flat Major, "freely transcribed" by Enrique Granados (acoustic recording)

Enrique Granados, piano

Pierian 02 54:49

Summary for the Busy Executive: Spanish Biedermeier.

Spain was one of the last European countries to experience musical nationalism. It more or less begins with Albéniz (1860-1909) and Granados (1867-1916), who glued a layer of Spanish melos over a Chopin base. Beginning at that point, Falla (1876-1946) brought the new language to its height and then moved beyond to invent Spanish Modernism.

Truth to tell, I greatly prefer Falla to Granados or Albéniz, mainly because I'm not all that fond of the ethos of what I term salon music. The idea seems to me to charm without challenge, and there are just so many marshmallows I can eat. I do recognize that certain pieces in the genre are miles better than others. Chopin, Liszt, Granados, and Albéniz write more substantially than Badewska or, say, Liadov. I also prefer Granados to Albéniz, who in general fails to grab my attention. Granados does at least that. However, Goyescas, I think, epitomizes my problem with the composer. This isn't the Goya who satirized the court, painted his nightmares, or raged against political repression, but the chronicler of Spanish peasant and middle-class life. For me, the pieces lack the fire of the burning Spanish sun. They sing of the hearth – or, rather, a slightly sentimentalized hearth.

Nevertheless, my quirks aside and on its own terms, it succeeds in spades. The length of each piece particularly impresses. It's not that any movement runs a marathon, but that given Granados's compositional habits, he can sustain a piece longer than four minutes. Granados isn't a musical architect, but a pure singer. Mainly, he improvises. I have to take exception to the liner notes on the disc, which mention "cyclical form." Granados doesn't employ cyclical form as much as he has certain riffs that he returns to, as the mood takes him. He doesn't concern himself with building a house, à la Mozart and Beethoven, as much as he does with sustaining a mood. Improvisers fall into two traps: meandering without ever finding a point or stretching a point beyond sustainability. The Goyescas focus. I've heard, by the way, Granados chamber music and tone poems, and they interest me far less than either the piano music or the operas. It's awfully hard for a composer who relies mainly on improvisation to do well in larger instrumental forms. Opera constitutes an exception, because words and drama carry a listener along almost as much as the music does. Granados, however, in his orchestral and chamber work falls into both pits.

On the other hand, it turns out that I hadn't heard a pianist who could persuade me, at least while the music played – not even De Larrocha, one of my favorite performers. Granados, however, convinces me in spades and wins me over completely. He first made his name as a pianist. On the basis of this CD, one can easily see why. From the opening measures of Goyescas, Granados plunges us into a rich, sensuous world of sound. There's a "weight" to the playing, like luxuriously heavy drapes, and an orchestral sense of color. Furthermore, the pianist follows the subtly shifting temperament of the composer. Without question, this is the finest performance of Goyescas – even though missing three numbers – I've heard.

In the Danzas españolas, Granados gets to show off his rubato, arsenal of touch, and absolutely formidable pedal technique. In the "Valenciana," one hears an essentially staccato articulation in which the line is neither dropped or blurred by the sustaining pedal. The pianist's ability to bring out whatever line he wants also impresses, so that the textural balance keeps changing.

The Valses poéticos never fail to charm me, miniatures bright with inspiration. If I were at all consistent in my likes and dislikes, I should hate them, of course, since they're salon music. What can I say? Perhaps I should mention that I've heard only great performers, including Julian Bream on guitar. Granados is simply one of the best I've encountered. He plays with a made-up-on-the-spot freshness.

As a nice bit of lagniappe, Pierian provides comparison recordings: Granados playing his own "free transcription" of a Scarlatti sonata in a Welte-Mignon roll and an acoustic recording made at roughly the same time. However, these aren't, strictly speaking, performances of exactly the same piece of music. Granados loved to revise, which of course has given generations of scholars and editors years of work as they prepare "definitive" editions. The roll comes from 1912 and the shellac from 1913. Nevertheless, the two formats allow us to find out exactly how much "historical" recording gives us. The acoustic recording shows us a clean attack and sprightly rhythms, but little else – a relatively flat sonic image. We get from the Welte-Mignon roll the depth of tone, the variety of color, Granados's subtle command of dynamic, from very soft to very loud in a seamless arc, and a fuller presentation of his ability to change textural balance and to bring out inner voices.

The recording should appeal to fans of Granados's music and of fabulous piano playing. Pierian has scored another hit.

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz