The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

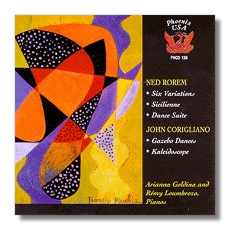

American Music for Two Pianos

- Ned Rorem:

- 6 Variations

- Sicilienne

- Dance Suite

- John Corigliano:

- Gazebo Dances

- Kaleidoscope

Adrianna Goldina and Rémy Loumbrozo, pianos

Phoenix PHCD138

Summary for the Busy Executive: Straw boaters and parasols.

I love four-hand piano music, on two pianos or one. In fact, I regret lacking the ability to play, mainly because I miss the pleasure of nibbling at bonbons like Bizet's "Jeux d'Enfants," Debussy's "Petite Suite," and Ravel's "Ma Mère l'Oye." Despite the presence of such serious masterpieces as Bartók's Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion or Hindemith's Sonata for Two Pianos, the medium very often shows composers at their most engaging and "clubbable." And why not? In the days when loving contact between the unmarried middle-class sexes came under much stricter supervision, the idea of close quarters with the object of one's affections under the cloak of the thoroughly respectable pursuit of parlor music-making had its attractions: chief among them, I suppose, the accidental touch of hands and fingers crossing over and under to reach the keyboard's notated destination. I always think of the old Tabu perfume ads where Victorian guy and girl, obviously stirred by the music, suddenly clinch and kiss to the point of swooning in front of the grand piano.

I don't normally turn to either Rorem or Corigliano when I don't know what I want to listen to, and, excepting certain works by Rorem, I have held no especial affection for most of the items in their catalogues. In fact, I've never really understood why Corigliano has a composing career, let alone such a successful one. Granted, he knows his craft, but the musical personality always struck me as "faceless" and the ideas as unmemorable. In short, neither sufficiently backs up Corigliano's considerable artistic ambition.

Consequently, I walked up to this CD with a certain initial lack of enthusiasm, which dissipated immediately on hearing the music itself. Each composer is represented by spirited diversions as well as by slightly weightier works, although nothing on the CD will really furrow your brow, and they don't mean to.

Rorem wrote the 6 Variations as a competition piece, and it speaks volumes that he fills the expectations of such a work - seamless trading-off of primary interest between the two performers, clarity of texture, shifts of mood calling for varieties of color, dynamics, and keyboard touch - while making poetry. There's also Rorem's usual guiltless eclecticism - a little Stravinsky here, a bit of Ginastera there, perhaps a touch of Poulenc - and yet the music doesn't sound ultimately like anyone else's. My problem with Rorem generally begins when I perceive as a weakness in some of his ideas, fortunately not here. This work catches hold immediately and keeps interest. Goldina and Loumbrozo turn in a superior performance, achieving a melancholy depth in the first and second variations, rhythmic precision in the nervous third (with more than a hint of chords from Stravinsky's Le Sacre over a Ginasteran rhythm) and sixth, razor-sharp trade-offs in the eccentric fourth, poetic delicacy in the fifth, and so on. All Rorem's borrowings serve a different, "chummier" sensibility than the sources. It's the pleasure good conversation gives you. I complain about the Sicilienne only because it's not really that, but a slow waltz. Still, it sings, and the performers seem to inject a large dose of wistfulness into their playing.

Corigliano began Kaleidoscope (1959) as a student of composer Otto Luening, one of the work's two dedicatees. The title, of course, implies shifting patterns and colors, and Corigliano proceeds largely by juxtaposing little thematic bits, like chunks of colored glass. There are two sets of these - a very rhythmic group and a lyrical one. The overall form of the piece is simple A-B-A, with the lyrical ideas sounding in the middle. The interest consists in the momentary juxtapositions, which never become predictable, and I should credit Goldina and Loumbrozo's transparent texture through a great dynamic range and spectrum of contrapuntal complexity as a significant contribution to putting the piece across.

The remaining works on the disc share a certain sensibility. Rorem talks of the unconscious influence of Bernstein's On the Town idiom in the "Overture" to his Dance Suite (1949). In fact, Rorem orchestrated this movement for his Third Symphony, written (appropriately enough) for Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. Even more insistent, however, is the relation between Rorem's work and Samuel Barber's Souvenirs, in its original piano, 4-hands version. The Rorem predates the Barber by three years and the Corigliano by more than twenty. All of three suites, however, hang heavy with nostalgia for the band shells and hotel dances in the early part of the century. Indeed, the Rorem and the Corigliano even share movement titles - "Overture," "Waltz," "Tarantella." Of course, it's nostalgia for a time none of the composers lived through. The nostalgia comes to all three second-hand, so to speak. Rorem wrote his work at age 25 in North Africa, where he lived at the time, so the bouncy American pop and (in his phrase) "jazz clichés" seem a bit incongruous. Homesickness? At any rate, the music is as playful and cute as a new puppy. The music doesn't differ that much from the 6 Variations, which may tempt one to think that Rorem found his style early. One should avoid that temptation. Rorem's expressive means and range have grown since then. I'd attribute the similarities to the tendencies, mentioned above, of the 2-piano medium itself.

Corigliano's Gazebo Dances sing with a less pronounced American accent and seem to derive from Stravinsky's two sets of Pièces faciles for 4 hands. I find the work less memorable than the Rorem, with some routine fill-work, but it still charms, especially the final "Tarantella," with its insistence on its main theme, like the leaps and bounds of a happy Lab.

Throughout, Goldina and Loumbrozo take an almost orchestral approach to their playing. In what often becomes fairly dense counterpoint, they always come up with the most important thing going on at the time, and they adjust balances instantly. This kind of performance takes planning and care. The music may not be as solemn as Bartók's, but it gets that kind of commitment from the players. Their ability to emphasize and fall back is instantaneous, and it always serves the music. They gorgeously articulate the arch of every movement. The sound and stereo separation are clear and as close to "real audio life" as these things get. Attractive stuff.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz