The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Postwar American Chamber Music

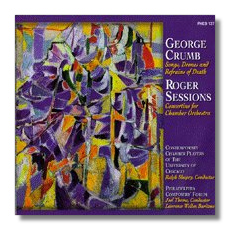

- George Crumb: Songs, Drones and Refrains of Death

- Roger Sessions: Concertino for Chamber Orchestra

Lawrence Weller, baritone

Philadelphia Composers' Forum/Joel Thorne

Contemporary Chamber Players of the University of Chicago/Ralph Shapey

Phoenix PHCD137

Summary for the Busy Executive: Non-disco from the 70s.

Well, not quite. George Crumb finished his Songs in 1969. But I associate both works with the 70s, because that's when I first heard them. The CD really took me back. Both composers were incredibly hot tickets in the new music scene back then. Crumb has faded somewhat from notice. One could never call Roger Sessions popular, exactly, but he did have a powerful advocate in Andrew Porter, hands down the best classical-music critic the New Yorker ever gave a byline to. But it amazes me how the musical landscape has altered in nearly thirty years. For one thing, young composers haven't fallen in with the "inevitable" march toward total serialism. For another, the minimalists – back then usually regarded as California nut jobs or Traitors to Their Class – opened new avenues for exploration in a way that post-Romantic composers could not. Yet, they made the world safe for the post-Romantic as well. Regardless of future consensus on their works, I believe they loosened up the culture in a positive way, reducing the snobbish outrage of the guardians at the temple of art to impotent whimpers – as far as I'm concerned, a step in the right direction.

Both pieces originally appeared on the Desto label, of sainted memory – one of the most eclectic and enterprising companies that mined mainly the lode of modern American music – and I am thrilled Phoenix/US has decided to resurrect the catalogue. Some really good stuff has already been released, including works by Barber, Brant, Britten (the label never was parochial), Corigliano, Martinů, Fine, Flagello, Harrison, Husa, Kirchner, Lees, Mennin, Menotti, Moore, Rorem, Schoenberg (the delightful string quartet concerto), and Yardumian. There's some very fine stuff to come.

In my fondness for reminiscence, I probably have given the mistaken impression that Crumb and Sessions – two of the most independent minds in postwar music – were typical 60s and 70s composers. Nevertheless, they benefitted from the fashion of – not "difficulty" exactly – but of certain kinds of difficulty. In Sessions' case, it showed itself in craggy melody lines and intricate counterpoint. On the other hand, Crumb's "arrhythmia," concern for new sonorities, and largely gestural procedure drew a sympathetic response among the foundations and programmers for new music. It's hard to say what influence Sessions has had, since his pupils – Diamond, Babbitt, Kirchner, and Kim among them – write music so different from Sessions' and from each other's. In any case, Sessions really had no theoretical agenda, other than quality and the concern to produce what he considered "classic" pieces. Younger composers, however, steal regularly from Crumb. Joseph Schwantner, for example, has made a nice career by "taming" Crumb's innovations. In this, Schwantner hardly stands alone.

Crumb seems to have become obsessed with the poetry of Lorca during the 1960s, creating a multi-work cycle, which Songs, Drones and Refrains of Death crowns. In an era when many composers appeared to write the same institutional-beige piece, Crumb fashioned a personal, largely experimental musical language. Yet, he remains a highly poetic composer, which is to say that the works are strange, beautiful, and powerful. Some composers take off from melody. Others want mainly to tell stories or build arguments. Crumb's composing imagination seems primarily "painterly." One gets visual as well as aural impressions from the scores. To some extent, of course, this may be due to the visual strength of Lorca's poems, but I would also say that Crumb's music – possibly because of the "space" around its constituent individual gestures – evokes wide landscapes and high night-blue skies or the glare of noon. Incidentally, if you get the chance, take a gander at Crumb's scores, even if you don't read music. They are gorgeously done, and every staff, dot, and line the composer's pen has put there. They should award art prizes to Crumb's manuscript all by itself, and the music sounds even better than it looks.

So well do Crumb's Lorca settings succeed that when I think of Lorca's poetry, I think of Crumb's music, just as Housman's poetry brings up Vaughan Williams' music in my mind. In fact, I believe that a composer confronted with the problem of Lorca's poetry would find it difficult to get away from Crumb. Whether Lorca's images suggested to Crumb a certain kind of music or whether Crumb found that certain Lorca poems fit the music he already wrote, I can't say. And yet others have found their own way – Falla, Barber, Poulenc, and Rautavaara among them. In fact, I found comparing Crumb's and Rautavaara's settings of "Canción de Jinete" ("Song of the Rider") very instructive. Rautavaara's music moves to a gallop, realizing the implications of the title. Crumb's music throughout the Songs and Drones is mostly static, mirroring the deep stasis of the imagery. The poems Crumb chooses have no narrative action. They string together mainly motionless pictures, and the music reflects this. Crumb chose the word "drones" well – the music so often consists of a fundamental tone (or pedal point) over which short bursts of rhythmic activity take place. The listener, I believe, must take "songs" with a grain of salt. These aren't melodies, but the human voice is absolutely essential to their effect, in "Spanish" vocal riffs, Sprechstimme, angry blasts. Voices give the music its considerable drama and passion. My favorite setting is undoubtedly the last, "Casida del Herido por el Aqua" ("Casida of the Boy Wounded by Water"), which talks about a nighttime visit to a fountain containing a stone sculpture of a boy, cracked and damaged by the water. For Lorca, the beauty of the fountain and its "wounds" are inseparable – again, a strange beauty musically evoked by Crumb.

The Songs and Drones poses the main problem of keeping the music moving. Crumb wants to give the impression of "ecstatic stasis," but the music can't really remain static. Through the almost glacial tempi and the long silences, "the next thing" had better arrive before the listener tunes out. A glacier may move slowly, but it does indeed move. The Philadelphia Composers' Forum and conductor Joel Thorne not only give you Crumb's precisely-imagined new colors, but the dynamism of one color to the next. Thorne realizes the considerable power of the Songs. He and the performers are so "in" and "with" the music, it reminded me of the line from Blake's "Mental Traveller": "Her fingers number every Nerve." If you don't like this performance, perhaps Crumb isn't for you.

Excepting some early compositions, I long entertained very little affection for or interest in Roger Sessions' music. It seemed to me that it never breathed, and that the composer was so interested in shoving in another line that the point of the music got buried under all the notes. Then I had the great fortune of performing Sessions' music, and I turned around completely. My revelation came during rehearsals of the final scene from his opera Montezuma. What had seemed to me cramped, crabb'd, and "cerebral" suddenly struck me as big, bopping, Meyerbeerian grand opera, with more distinguished music and libretto. Sessions was a misunderstood Romantic, whose music took big breaths and strides. Above all, one had to catch the "singing line" of Sessions, like Brahms, another composer condemned in much the same terms during his lifetime. Of course, both fashion their music with immense craft, but the craft is never the point. It always serves expressive ends. Come to think of it, I came around to Brahms (a bit late; I was in my thirties) at roughly the same time.

Sessions' music hasn't received all that many recordings. Off-hand, I can't recall a duplication, with the exception of the Black Maskers suite. I certainly don't often encounter his name on programs. I grant its difficulty, but it's powerful stuff. It needs performers willing to explore it and stick with it. The Concertino comes late in Sessions' output, and it's relatively modest in its dimensions (Sessions used to joke that he had difficulty writing something "small"). The performers here premièred the piece. We get no information as to the recording date, but I suspect that it probably happened close to the première. The players get the notes (it's a very precise performance), but they miss the music. The work comes across as curiously expressionless. The counterpoint is almost preternaturally clear, but this could stem from Sessions' orchestration. Shapey doesn't seem to sense which lines are important. Above all, everything reaches the ear in short, choppy bursts. The arch of the music is nowhere in sight. The slow movement's the giveaway that something is wrong. The phrases are longer, but they are merely played, not sung. Furthermore, there's little connection of one phrase to the next or comprehension of the rhetorical relation of each phrase to the whole. The Concertino badly needs another, more sympathetic recording.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz