The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rimsky-Korsakoff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

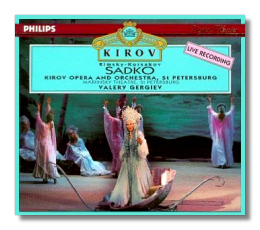

CD Review

CD Review

Summary for the Busy Executive: A wonderful opera which needs a wonderful recording.

Censorship works in mysterious ways. Most 19th-century Russian opera falls into the category of costume drama, peasant comedy, or fairy tale, probably because the censor was so strong. In fact, I can think only of Tchaikovsky's Yevgeny Onegin off the top of my head that purports to tackle a serious, relatively contemporary subject, even though one without obvious political overtones. Thus, we have Mussorgsky's Boris and Khovanshchina – tales of the Bad Old Days – but not a Fathers and Sons. Rimsky writes a Tsar's Bride, May Night, and a Tale of Tsar Saltan – pseudo-historical romance, Those Crazy Muzhiks, and Russian (rather than Arabian) Nights, respectively. Of course, artists found ways to sneak around the censor, and Rimsky's own fairy-tale Coq d'or is a thinly-disguised satire on the tsars – perhaps too thinly, since the censor banned it.

Rimsky's career divides neatly in half: concentration on orchestral music in the first half; concentration on opera in the second. In the case of Sadko, Rimsky builds an opera from themes of his purely instrumental tone poem of the same name, written thirty years earlier. If you think of opera as primarily drama, I would regard only The Tsar's Bride of all of Rimsky's operas as a success – but what a success! I rate it only slightly lower than Mussorgsky's Boris and on a par with Tchaikovsky's Pique Dame. In general, however, Rimsky, I think, had better luck with his fairy tales and peasant comedies.

Neither Sadko's plot nor characters count for much. Much of the libretto doesn't make even immediate sense. In his autobiography, Rimsky traces the inspiration of the opera to the scenery of his country retreat, rather than the story per se. He even admits that he composed many of the most admired numbers in the work because he felt the need for something in a particular key. The story goes by quickly. To the merchants of Novgorod, the minstrel Sadko proposes to lead a huge trading expedition. This is a bit like me telling Bill Gates how to run a successful software company. No surprise – they turn him down. By the waters of Lake Ilmen, there Sadko sits down, yea, he weeps 'cause everybody treats him mean. The Sea Princess and her entourage (what they're doing in a lake, I have no idea) hear the song. The princess offers to become his groupie. Sadko, temporarily forgetting he's got a wife at home (moreover, living on a minstrel's salaries and tips), launches into a duet with the princess, in which both swear eternal love. Near the end of the scene, Sadko finally says, "Oh, yeah. I'm married." The Sea Princess tells him she'll wait and prophesies a big future for the young man. At this point, it could turn into Tosca or at least Frankie and Johnny, but that would ruin the pretty pictures. Back at home, Sadko's wife sings about how much she misses him. Despite the flippant tone of many of my remarks about the plot, this aria zings the strings of my heart. It sings in what we've come to think of as a "typically Russian" way. But this is largely Rimsky's and Mussorgsky's invention and their elaboration of folk sources. Sadko returns, but he seems a bit distant and leaves almost immediately, giving his wife the opportunity to be sad some more.

By a subterfuge (too idiotic to detail) provided by the Sea Princess, Sadko gets the Novgorod merchants to back his voyage and becomes rich at a stroke, or rather their strokes. Since this is a fairy-tale rather than corporate hardball, they live up to their agreements. Just before he goes, his wife runs onstage and begs him not to go. He tells her he's a ramblin' kind of a guy, asks her to forgive him, and leaves to the cheers of everybody else. Obviously, there are no divorce lawyers in Novgorod, but in any case Sadko's outta there.

The voyage takes twelve years, but Rimsky wisely omits the sordid details of buying and selling. We find Sadko out on the sea, his ship at a standstill, as other vessels pass him by. It seems he's behind in his tribute to the Sea King, having never offered any. He determines that by now the only tribute satisfactory to the king is his own self, so he maroons himself on a raft in the middle of the ocean and after the ship sails away, hooks up again with the Sea Princess who brings him down to the realm of the Sea King. Sadko squares things with the king by singing for him. Here, Rimsky makes the most obvious use of the earlier tone poem and reveals that his symphonic method really is the ability to write a very long song indeed, rather than to weave intricate patterns. Much of the instrumental work goes straight into the voices with hardly any adjustment. The king grants Sadko his daughter's hand in marriage, and Sadko eagerly agrees. The king commands Sadko to play again, and this time king and subjects get down with their bad selves to such an extent that the oceans roil, storms storm, and rivers overflow. Suddenly, an ancient warrior appears in the guise of a pilgrim. The party stops. The pilgrim breaks the power of the Sea King, condemns the kingdom to the darkest deep and deepest dark, and returns Sadko and the Sea Princess to Novgorod. The Sea Princess lulls Sadko to sleep, and, having made up her mind to do the noble thing, turns herself into a river. Sadko reunites with his wife who, incredibly, begs him to forgive her (a clue that this was written before women's lib), and the chorus welcomes back the local boy.

I'm convinced that, in this country at least, very few opera fans care about drama and go to hear big singing and look at pretty scenery and costumes. Rimsky's operas fit this public and a house such as the Met like a custom truss. They're also glorious music. The orchestration is as sumptuous as a baked Alaska. A successful performance depends on pretty singers, shifts, and sets and a really good orchestra. Rimsky's music blazes in the Novgorod crowd scenes, where he plays up the added color of the opera chorus to the hilt. Nobody, including the principals, really has to act, and the vocal demands are slight, compared to Verdi, Puccini, or Wagner. The arias are really sort of extended parlor ballads, composed by a melodist of genius. So most companies, including the Met, could produce this opera rather easily.

Philips recorded this opera live in Russia, which is to say on the cheap. Gergiev and the orchestra do very well for a live reading. Occasionally, one can detect small rifts in the ensemble. The brass make the most obvious errors, because you can hear them over everybody else: mostly a matter of trumpets not quite making the high notes. The chorus keeps up with the orchestra. Diction becomes a bit cloudy, but since I don't speak Russian, it doesn't really bother me. The principals make the weakest contribution, almost stereotypes of Russian singing: woofing bass, bleating tenor, wobbly mezzo, hard-edged soprano, and all with a fairly vague idea of the correct pitch. Marianna Tarassova, as Sadko's wife, stands out as far and away the best singer of the lot, but how she would do among a better cast, I can't say. Balances in the big scenes are, predictably, not as sharp as they would be in the studio, but you can live with them.

I know of no other recording of this work currently available. It's fabulous music, lavish as the Tsarist jewels. It bedazzles. If you don't mind overdosing from pure pleasure, you might very well indulge yourself with these discs.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz