The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Arensky Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

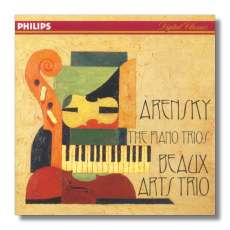

Anton Arensky

Piano Trios

- Piano Trio #1 in D minor, Op. 32

- Piano Trio #2 in F minor, Op. 73

Beaux Arts Trio

Philips 442127-2

Rimsky-Korsakov predicted oblivion for Arensky, and he just about had it right. Excepting the first piano trio, people have forgotten Arensky's music. I've heard several works by Arensky, and I think the chances slim we will discover either a neglected Brahms or a neglected Rimsky, for that matter. Nevertheless, we listen to all kinds of music for all kinds of reasons, and not everything need give us a vision of heaven.

The trios, I believe, show Arensky at his attractive best, for the music is indeed attractive. The first especially shows off a genuine lyrical gift. The themes in fact are the work's main strength, with a Slavic melancholy cast to some of them and, oddly enough, a Mendelssohnian reminiscence to others (the Scherzo especially). If I had to guess when Arensky work, I would have guessed around 1860, one year in fact before the composer was born. There's almost no hint that Arensky has heard Wagner or Brahms or Liszt, and perhaps he hadn't. Yet, he should have gleaned something from the Five and from Tchaikovsky, the latter supposedly a great influence on him - perhaps so, in the way Russian folk influence on his themes has been sublimated. Still, you listen in vain for harmonic daring or structural genius. Development is often a matter of mere sequence, there's far too much reliance on "call and response" between violin and cello, and the distribution of musical interest never really varies. Instead of (to me) a chamber ideal of a colloquy of equals, Arensky relies on melody-basic accompaniment-figuration. Further, basic accompaniment he almost always gives to the piano. To some extent, it reminds me Saint-Saëns's chamber music, but not nearly as interesting. The slow movement stands apart from the schoolboy development and dilettantish textures of the rest. Here, Arensky seems free and does what he apparently wants: to sing. He lays down a melody and follows it with increasing fervor, mining it for maximum expressivity.

The second trio, written a mere ten years later near the end of Arensky's short life, shows huge improvement in constructive ability. Now the relationships among instruments come more in line with the late-Romantic chamber-music norms of Brahms, Dvořák, Bruckner, and Franck. Still, this comes at a price. The themes themselves are pallid. After several listenings, the work goes by and I retain very little. For me, the best of the movements is the theme-and-variations finale, possibly because I get to hear the theme over and over again and so become impressed by it.

The Beaux Arts Trio needs no puff from me. It gives both works as good and as loving a treatment as they are likely to get.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz