The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bortkiewicz Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

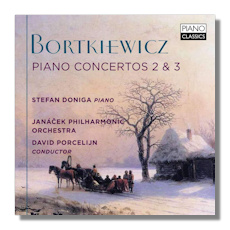

Sergei Bortkiewicz

Concertos for Piano

- Piano Concerto #2 for the Left Hand, Op. 28 (1922-23)

- Piano Concerto #3 in C minor, Op. 32 (1926-27)

Stefan Doniga, piano

Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra/David Porcelijn

Piano Classics PCL10146 58:32

To call Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877-1952) a musical conservative is a bit of an understatement: these two concertos, for instance, come from the 1920s as you can observe in the heading, but they undeniably exhibit piano writing and orchestration that would not have been out of place in the late 19th century.

Bortkiewicz might be compared with Rachmaninov in many ways, a composer who also never quite adjusted to 20th century styles but at least, despite academic detractors who predicted his artistic demise, became a major figure in the company of the more progressive Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Bartok and others. Bortkiewicz remained on the sidelines with other conservatives, prominent among whom was Medtner, who was often called a Rachmaninov clone. But it wasn't his conservatism that held Bortkiewicz back: Rachmaninov wasn't the exception in achieving success – Ralph Vaughan Williams also succeeded as did, but to a lesser extent, Erich Wolfgang Korngold.

Bortkiewicz is less prominent today because his music lacks an individual stamp, a distinctive voice. In these concertos, for instance, at times you hear Liszt, and at others early Scriabin or Rachmaninov. Those influences might be understandable in a young composer finding his way, but these works are from the composer's mature years. Paradoxically though, while these concertos look unashamedly to the past, they also look ahead: Bortkiewicz is clearly prescient of a coming trend, auguring a sort of movie music style that would appear in many motion pictures from the 1940s and 1950s. Related to this was a trend known as ‘tabloid concertos', short works which appeared in films from the wartime and post-war era. One can think Miklos Rosza's Spellbound Concerto, Charles Williams' Dream of Olwen, and probably most famously Richard Addinsell's Warsaw Concerto. Maybe one can even toss in Dmitri Shostakovich's rather sappy The Assault on Beautiful Gorky. Bortkiewicz's music here is better than these examples, though it isn't exactly masterful. That said, it's pretty good still.

Both works are very rarely performed today and sometimes strike the listener as episodic in their odd structures. The Second is for the left hand alone and was written for Austrian-American pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm in World War I. Wittgenstein is best known not for his pianism but for the concertos he commissioned from Ravel and Prokofiev, among others. Strangely, Wittgenstein rejected the Prokofiev concerto (#4), a work which was premiered in 1956, three years after the composer's death. Wittgenstein claimed not to understand the work (actually, not a particularly challenging piece for the listener), which goes to show that he too had very conservative tastes.

Wittgenstein premiered the Bortkiewicz Second in November, 1923 and played it many times thereafter, right up to 1961, the year of his death. As far as we are concerned here, I can say this concerto is not a great rediscovery. On the plus side, the music is interesting for its several attractive tunes and skilled, if not always imaginative piano writing. In the end, this four movement work wears thin on repeated hearings, striking you ultimately as pleasant but not a major work. It gets a fine performance though from Romanian pianist Stefan Doniga, and his conductor here David Porcelijn draws spirited and accurate playing from the splendid Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra.

The same forces offer just as compelling an account of the Third Concerto, which is the better work here. Not that it is a masterpiece of profound consequence, but it is one of those compositions whose themes stick in the mind long after hearing and whose sincere emotional outpourings can win the listener over, the work having the stuff of an irresistible guilty pleasure. Of the five sections (which are played continuously) the last two are the most effective and most memorable, primarily because Bortkiewicz invests each with very catchy themes, even if he gets a little repetitious. Without doubt, some listeners will be immediately caught up by the sweep of the music's lush if superficial beauty and its somewhat saccharine triumphant sense. It's the kind of work that Tchaikovsky detractors and academic sophisticates will love to ridicule, while the fair-minded will hardly deny its great appeal. In a sense, it is music whose uneven parts are greater than its seemingly modest sum.

The work has a subtitle, Per aspera ad astra (Through resistance into light), which might suggest something profound, but it is far more emotionally charged and dramatic than philosophical or ponderous. One could analyze this concerto more elaborately, as well as its disc mate here but, as already suggested, Bortkiewicz is less about form and development and more about melody and drama.

The concertos were recorded in June, 2008 and originally issued by the Nederlands Muziek Instituut. The recorded sound is well balanced and very clear, and the album notes informative. These well played and rarely encountered works are probably worth your attention, especially if very accessible music in the post-Romantic vein is your cup of tea. Interested collectors will probably not get the chance to acquire performances this good for some time.

Copyright © 2018, Robert Cummings