The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Schubert Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

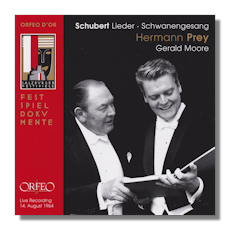

Franz Schubert

Lieder

- Der Sänger, D. 149 (early version)

- Harfenspieler I "Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt", D. 478

- Harfenspieler II "Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen ass", D. 480

- Harfenspieler III "An die Türen will ich schleichen", D. 479

- Song Cycle "Schwanengesang", D. 957

- Der Musensohn, D. 764 (encore)

- Im Abendrot, D. 799 (encore)

- An Sylvia, D. 891 (encore)

Hermann Prey, baritone

Gerald Moore, piano

Orfeo C911151B AAD

This recital of over 20 songs by Schubert with baritone Hermann Prey (1929-1998) accompanied by Gerald Moore (1899-1987) was recorded in August 1964 at the Mozarteum during that year's Salzburg Festival. On the one hand it shows its age with the acoustic sounding dry (despite that auditorium's capacity of over 500) and somewhat flat, wooden in this analog (tape) recording and mixing; and Prey certainly not closely miked – at least in the first few songs of the recital… was something changed at the interval? On the other hand, the singing and delicate, responsive pianism of Moore allow every nuance of Schubert's subtle melancholy to emerge. More telling, perhaps, are the ways in which Prey and Moore illustrate the variety and richness of Schubert's writing as clearly and sympathetically as his mournfulness. This is a recital to treasure.

You're also likely to be struck by the difference in style of delivery of 50 years ago: declamation, heightened drama, gesture and an at times almost total inhabitation of the poetry and its sentiment mark such songs as "Wer nie sein Brot" [tr.3]. This expression of despair from Goethe's "Wilhelm Meister" seems at times destructive; it's effective when little or nothing is held back (Goethe was working at a point in the transition from Classical detachment to full Romantic dolefulness). Yet the performers always have much in reserve, and do not over indulge. This is because their conception of the poetry was one which identified much more closely with the heart of the protagonists than has since become fashionable and would be found in a Padmore, Goerne or even a Fischer-Diskau. Not heart-rending, not unduly plangent, yet focused, full of appropriate distress and regret: listen to "Am Meer" [tr.9] from the Schwanengesang, for instance, to get the very strong pulse of these two supreme experts conveying what Schubert surely wanted the music to convey and no more or less.

The program was designed to evoke the Liederabend, or evening song recital, which at that time was felt to have fallen somewhat out of use – particularly in the context of a major operatic festival. For this recital Prey and Moore made what, now and then, must be regarded as an unconventional selection. As if to set the scene, it began with the early "Der Sänger" (The Singer), and the three Wilhelm Meister harpist songs. "Schwanengesang" they split into two groups, altering the more usual order arrived at by Schubert's friends and publisher after his death. Here we have the Heine six and Seidl, "Taubenpost" before the interval; the Rellstab seven after it. Three of Schubert's most famous Lieder formed the encores: Der Musensohn (D764); Im Abendrot (D799) and An Sylvia (D891). The whole is nearly 80 minutes.

Prey's first (such) recital at Salzburg was only three years earlier, in 1961. He went on to complete almost 30 more until the summer of 1997. In these years, in the 1960s he – like Moore – was at his peak… sweet, bursting with melody and pathos, authority (listen to the opening of "Aufenthalt" [tr.16], for example), confidence and color. Above all, his baritone, light in dynamic, though not in range, blended to perfection the temperament of Schubert's sense of the tragic loss and regret with the gentle detachment needed to make these searing songs art and not therapy! The intensely depressing Harfenspieler II "Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen ass" (D480) [tr.2] is a good example of this style.

Musical lines are crafted; pauses carry all the weight they need to; telling words, "Tränen" (tears), "Abschied" (farewell), "Herz" (heart) have no need to receive undue pressure. Yet vowels are held just as long as they should be held, Prey's breath is taken in and let out in yet another felicitous co-incidence of emphasis with naturalness. Moore is lighter and less insistent than he was in many of his later recordings. But his support is ideal. We're aware of the piano and its deft weaving and counterpoint. But it comes from a place of intimate knowledge of the text, which is what matters. At times – as at the end of "Abschied" [tr.18], for instance – it adds extra musicality. Moore's tone, indeed, is lyrical, singing; it's as light as Prey's is engaged. Rhythmically disciplined, it too marries the apparently spontaneous – accidental, almost – with the directed and safe.

The characteristic that's perhaps most likely to please, and which one doesn't always hear in recitals nowadays, is of unforced engagement without display or false reticence: "This is our job, our skill; we're here to sing and play; we love Schubert; we know you do. That's all that's really necessary. Thank you!" This combination of unashamed expertise and humble confidence seems to be reflected too in the sequence of songs: the center is clearly the darkness of Schwanengesang, but there's a build up to that in the Wilhelm Meister settings and a relaxation in the three encores.

Despite its age, few will be disappointed at the acoustic of this CD from Orfeo; audience noise is minimal – though the applause is loud and long-lasting. And, although there's not much sense of atmosphere, this is clearly the recording of a recital at an exciting time for the Festival, as almost all of the first page of the four page essay by Gottfried Kraus that comes with this CD explains. The recording does show its age very slightly, though, in the lack of rock steady pitch in the piano. This is not something to put listeners off.

This recital by Prey and Moore was seen at the time as a statement reasserting the role, place and right of the Lied in such festivals… to commemorate Strauss' centenary there was an Ariadne and Elektra that year as well as Macbeth and much Mozart of course. The narratives and excerpts from other contemporary writers set this scene nicely in the booklet. The texts are not reproduced here; though they can easily be found online and in the standard texts. This was a classic and memorable occasion.

To have these wonderful performances is a delight. Lovers of Schubert, the Lied, Prey and Moore and a style of performance and projection from another age still as fresh and full of impact as it must have been in 1964 should not overlook this CD.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Sealey