The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rautavaara Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

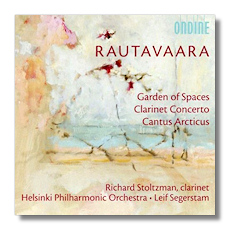

Einojuhani Rautavaara

Classic Modernist in an Avant-Garde World

- Garden of Spaces (1971/2003)

- Clarinet Concerto (2001)

- Cantus Arcticus (1972)

Richard Stoltzman, clarinet

Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra/Leif Segerstam

Ondine ODE1041-2 59:08

Summary for the Busy Executive: Sibelius updated.

Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara (b. 1928) has always gone his own way, but the restlessness of his mind has led him down many different ways. He's not a composer readily-identifiable after a few measures or even one piece. That usually means that a writer has very little of his own to say, but in Rautavaara's case, the opposite strikes me as truer. He has almost too much of his own, and he wants to express it all, rather than settle into any particular groove. Rautavaara's music says more about qualities of mind than musical language.

After studies in Europe, Rautavaara came to the United States where he worked with Sessions, Copland, and Persichetti. His music shows a duality: an interest in European avant-garde techniques allied to an old-fashioned, classic Modernist musical architecture and sensibility. In this regard, one might compare him to composers like Hovhaness, Tippett, and Britten in his final phase.

Cantus Arcticus (Concerto for Birds and Orchestra), for example, shows these opposite tugs immediately. His most popular piece (to judge by the number of recordings currently in the catalogue), it uses bird cries on tape and symphony orchestra. The work consists of three movements – "The Bog," "Melancholy," and "Swans Migrating" – which melt into one another. Rautavaara asserts the tapes have been processed "very little," but that's relative. The bird cries have been in some cases slowed down and lowered in pitch, as well as overdubbed. I myself consider that considerable processing. The piece's use of nature's sonic phenomena with orchestra may remind some of Hovhaness's And God Created Great Whales, and indeed Hovhaness got in there first (1970). But tape-and-orchestra was "in the air" in the Sixties and Seventies, so no originality points for either composer. However, both works share the use of nature to generate musical ideas.

The contemporary element in the piece, of course, is the use of tape, but we can instructively compare typical post-war use with Rautavaara's procedure. Contemporary music, at least in the Seventies, tended toward stasis. Composers seemed to think of music in almost spatial terms. Thus, bird song might be foreground accompanied by orchestra as backdrop or "color." The orchestra shimmers while the birds twitter. Some of this goes on in Rautavaara, but mainly the orchestra pushes forward a musical argument. In the first movement, for instance, once the birds have begun, the orchestra chatters with them, but gradually various sections begin to establish a fragmented pulse, which strengthens as the movement proceeds. A full-blown melody comes out, and, oddly enough, it's a melody that wouldn't have been out of place in a Sibelius tone poem. In the finale, Rautavaara begins with overdubbed swan cries. Imitating them, the orchestra enters in extreme stretto, but again a long-limbed melody grows out of the hubbub, before the birds return in the coda and fade out.

Garden of Spaces, a tone poem, rose from the inspiration of an exhibition of the same name by noted Finnish architect Reima Pietilä. Rautavaara had "an idea for a work that could be different in each performance." Of course, every work played by humans differs from one performance to the next, but Rautavaara had in mind a link to aleatoric (chance) music, very much talked about and resorted to at the time. Indeed, one could argue that John Cage's influence, particularly in Europe, touched painters, writers, and sculptors more than it did musicians. Rautavaara's "chance" manipulations are far more subdued than Cage's. He thoroughly composed large blocks of music – Legos, if you like – but designed those blocks with the ability to be played in any order, simultaneously, or interleaved. He leaves it to the conductor to cue what he wants. I heard the piece before I read the liner notes, and I can say that the method didn't occur to me. It struck me as an idiosyncratic take on musical Impressionism. So you don't have to know Rautavaara's methods to enjoy the music. However, once you know the methods, you can have fun spotting the blocks.

One listens in vain for avant-garde elements in the clarinet concerto, written for Stoltzman. They seem more a matter of color and harmony, rather than anything deep in the architecture. In this concerto, the spotlight stays firmly on the soloist. There's very little give-and-take with the orchestra. What there is seems mostly for show: primarily, a dramatic opening, which promises Angst. Indeed, Rautavaara calls the first movement "Drammatico (ma flessibile)." But the most of the music runs on the slow side, more lyrico than drammatico. Toward the end, the dramatic very briefly reasserts itself, but the lyric wins out. The orchestra supports far more than it advances the argument, so you get the impression of All-clarinet! All the time! The slow second movement, another accompanied song, follows the slow first movement, and again the orchestra accompanies a gorgeous melody from the soloist. At this point, I realized the high quality of Rautavaara's invention. It takes real melodic gold and a virtuoso sense of variation to get away with two slow movements in a row. The vivace finale shows some of the traditional back-and-forth of the classical concerto. The balance, weighted toward the soloist (as you might expect), nevertheless seems more "normal" than in the previous two movements. The closer begins as a tarantella on an ascending theme, which ratchets up the level of excitement from the get-go. The clarinet introduces themes from the first movement, reduced nearly to virtuoso figuration at the new speed and elaborated with more filigree. But the music still comes across as lean and muscular.

Stoltzman doesn't need me to sing his praises. His main virtue is a gorgeous tone. If I prefer the phrasing of other clarinetists, I don't deny his virtuosity or his musicianship. It's damn difficult to take stage center and hold it, but hold it he does. And he doesn't sink in the mostly-continuous melody Rautavaara gives him. Most of the shape of the concerto, simply by the nature of the writing, comes from Stoltzman. On the other hand, most of the shape of Garden of Spaces comes from Segerstam, again due to how the composer conceived the piece. It must help tremendously when the conductor also composes, because Segerstam comes up with something poetically compelling. I can easily imagine a performance where the score lays there like a lox.

The recorded sound comes well within acceptable modern standards. I will say, however, that the dynamic level seems a bit low to me. You may have to crank up the volume.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz