The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Kokkonen Reviews

Lindberg Reviews

Rautavaara Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Society Of Finnish Composers 50th Anniversary

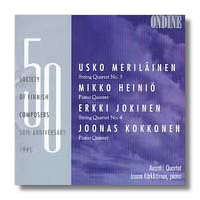

Volume 1

- Usko Meriläinen: String Quartet #3

- Mikko Heiniö: Piano Quintet

- Erkki Jokinen: String Quartet #4

- Joonas Kokkonen: Piano Quintet

Jaana Kärkkäinen, piano

Avanti! Quartet

(John Storgårds & Anna Hohti, violins

Tuula Riisalo, viola; Lea Pekkala, cello)

Ondine ODE865-2 DDD 70:36

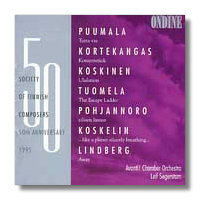

Volume 2

- Veli-Matti Puumala: Tutta via

- Olli Kortekangas: Konzertstück for Clarinet, Cello, and Orchestra

- Jukka Koskinen: Ululation

- Tapio Tuomela: The Escape Ladder

- Hannu Pohjannoro: the birds of yesterday

- Olli Koskelin: … like a planet silently breathing….

- Magnus Lindberg: Away

Kari Kriikku, clarinet (Kortekangas, Lindberg)

Anssi Karttunen, cello (Kortekangas)

Avanti! Chamber Orchestra/Leif Segerstam

Ondine ODE866-2 DDD 69:50

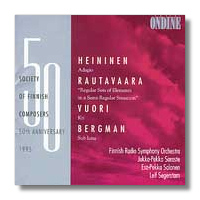

Volume 3

- Paavo Heininen: Adagio… concerto per orchestra in forma di variazioni… 1

- Einojuhani Rautavaara: "Regular Sets of Elements in a Semi-Regular Situation," Op. 60 2

- Harri Vuori: Kri 3

- Erik Bergman: Sub luna - Four Nocturnes for Orchestra, Op. 116 1

1 Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Jukka-Pekka Saraste

2 Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Esa-Pekka Salonen

3 Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Leif Segerstam

Ondine ODE867-2 DDD/ADD2 67:28

As the title of these discs suggests, the Society of Finnish Composers is celebrating its fiftieth birthday, but we're the ones who are getting all the gifts. Volume 1 is devoted to chamber music (most of it very recent), Volume 2 is devoted to larger ensembles and to Finland's Young Turks (the oldest composers on the disc are the two Ollis – Kortekangas and Koskelin – who were born in 1955), and Volume 3 is devoted to splashy works for full orchestra. Composer Aulis Sallinen is conspicuous by his absence. Is there a story here?

I'd like to cover the highlights of each disc, although choosing them was difficult – there's so much good and interesting music here. At its 1953 première, Joonas Kokkonen's Piano Quintet was the work that established him as a major and individualistic composer. (Interestingly, Kokkonen is more than modest about its importance.) The traditional-minded Piano Quintet's four movements are bound together by a motif whose melodic and rhythmic outlines are easy to follow throughout the course of the twenty-five minute work. Anyone who appreciates Shostakovich's masterpiece in this genre will appreciate Kokkonen's, although the Finn is less grotesque, more "Lutheran" in spirit than the Soviet.

For me, Volume 2's stand-outs are the pieces by Olli Koskelin and by Magnus Lindberg. In contrast to Kokkonen's Piano Quintet, Koskelin's brief work is sexual – perhaps not surprisingly, because it derives from a dance work. It opens with divided strings and restless harmonies. Slow, irregularly overlapping parts weaken the bar-lines. The oboe sings a thoughtful song, and the music intensifies and begins to strive upward. The steady, hollow ticking of a vibraphone imprints itself on the ear. After further ascending outbursts, the music becomes rapturous, but the rapture is followed by rest: oboe, strings, and a few specks of vibraphone bring the work to a close. Lindberg's Away, recently completed as a tribute to Polish composer Witold Lutosławski, features the clarinet, whose skirling figures certainly evoke the late Pole. The soloist grabs onto a striking theme and gallops along. Away turns elegiac right at its end, but then it does a disappearing trick and slips away before it has a chance to become lachrymose. This concise, five-minute work demands great agility from the soloist, but listeners won't have to flex too hard to "get it."

My favorite piece on Volume 3 is Erik Bergman's Sub Luna. Bergman was born in 1911 and has written many evocative works, especially for choral ensembles. The first of these "Four Nocturnes" opens with splashes of harp and high-toned percussion. Nervous rumblings from the bassoon and lower strings create a feeling of expectancy. It's colder than Schoenberg's Transfigured Night – mists are rising and the dew is falling to harden as frost. We move to the second nocturne without pause. Slithery strings and brittle rhythmic figures from an army of percussion suggest that someone – or some thing – is dancing in the dark. The listener is filled with atavistic dread. A xylophone solo with missing teeth cleverly accepts fillings from the wood block. The incantatory third nocturne is occupied by a mounting feeling of hysteria, of directionless running back and forth, and of nocturnal forces beyond our control. In the final nocturne, Wozzeck drowns once again, and several times more, to the sound of groaning wind figures and painfully dragging percussion. At Sub Luna's end, the bassoon whines like a young wolf separated from the pack for the first time. Overall, Sub Luna demonstrates that athematic music can be gripping when color and drama are valued by the composer.

The performances seem to do the works justice, and the engineering and presentation are excellent. This was a worthwhile project for this unusual Finnish label.

Copyright © 1998, Raymond Tuttle