The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

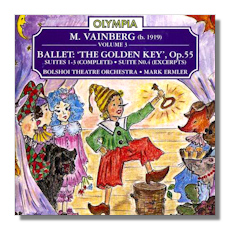

Mieczysław Weinberg

The Golden Key, Op. 55

Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra/Mark Ermler

Olympia OCD473 78:17

Summary for the Busy Executive: Wonderful.

"Fairy-tale" operas and ballets have always been pretty big in Russia, mainly due to the country's draconian censorship, first under the Romanoff and then under the Soviet tsars. It was a good way for a composer to avoid headaches or, with a good deal of guts and guile, to slip in political content. Of course, one can read a fairy tale in many ways, including a Socialist Realist one - which happened when Prokofieff's Cinderella fell into the interpretive hands of the Soviet press, which (with the passage of years) has become truly laughable.

Weinberg's Golden Key inhabits an ambiguous space. Alexei Tolstoy, a writer who understandably never wanted to make waves in the Stalinist state, provided the libretto. However, Weinberg's music takes the basic story to other places. For me, Weinberg is the third great Soviet composer, along with Prokofieff and Shostakovich. His musical idiom owes a lot to Shostakovich, and indeed he used to describe himself as a "pupil" of the older composer, although he never formally apprenticed himself. In fact, Weinberg was an already full-grown composer by the time he met Shostakovich, and Shostakovich not only helped him earn a living, but probably (and at considerable personal risk) saved him from "disappearance" during the anti-Semitic purges of Stalin's final years. Nevertheless, although Shostakovich and Weinberg share a certain musical language and iconography, miraculously neither becomes a trivial imitation of the other. Weinberg composes at Shostakovich's level, and over the years I've found him a less acidic artistic personality. There's something "warmer" (but not fuzzier) about Weinberg's music, and I've come to regard the two in roughly the same relation as Brahms and Dvořák. Still, Weinberg's idiom carries with it a sharply-satiric edge.

The story of The Golden Key mixes Pinocchio with Pétrouchka and a little bit of the beanstalk's Jack. As I say, the fairy-tale can be read many ways. The puppet-hero, Buratino, one can view either as a proletarian hero (he leads the other puppets in a revolt against the puppeteer) or as an anti-Soviet. He finds the golden key to the Country of Happiness, which implies that the Revolution isn't enough to make you happy. But who really wants to take a fairy-tale that seriously, if he doesn't have to?

For those who know Weinberg's symphonies, concerti, and chamber music, this ballet may come as a surprise. Weinberg has unbuttoned his buttons and poured into the work some of the most suave and delightful tunes in all of ballet. This is Poulenc-caliber, without Poulenc's idiom. The heavy shadows that cling to the orchestration of his more serious-minded works disappear. Indeed, the ballet might be viewed as a gallery of the great Russian masters of orchestration. Those familiar with Weinberg, of course, expect the quick, "grotesque" dances à la Shostakovich, but might be surprised by Tchaikovskian waltzes, Rimskian brass work, flashes of the Pétrouchka Stravinsky in the winds and in some of the dance rhythms, and gorgeous adagios of the sort Prokofieff's Roméo and Juliet taught Russian composers how to write. The ability to assume different characters and voices helps a story-teller vivify his tale. The uncanny thing is, none of these numbers merely imitates, any more than Thoreau imitates Emerson, even though both speak Transcendental Yankee. Weinberg has something of his own to say. But it's not just tunes. Weinberg the symphonist peeks out from backstage by giving the main characters motives that stick to them from one number to another.

Not that you can follow a story from this CD. Weinberg made four orchestral suites out of numbers from the ballet music, without the idea of keeping the armature of the plot. He positions the numbers according to the principle of effective contrast and climax within each suite. Furthermore, although Olympia gives us the first three suites entire, it excerpts the fourth. Nevertheless, this is a very generously-filled CD. Ermler and the Bolshoi do well enough, even though here and there the playing becomes a bit raggedy. However, I really want to hear what a first-class London orchestra would make of it. The music of this ballet deserves Tchaikovskian popularity and deluxe treatment. At any rate, kudos to Olympia for the Weinberg series in toto and for this disc in particular.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz