The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schoenberg Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

DVD-Audio Review

DVD-Audio Review

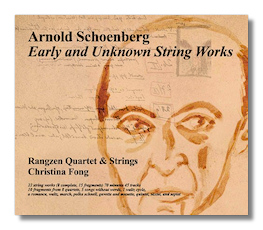

Arnold Schoenberg

Early and Unknown Works

- Sonnenschein-Polka for 2 violins

- "Alliance" Walzer for 2 violins

- Lied ohne Worte in B flat for 2 violins

- Idylles Lied ohne Worte in C for 2 violins

- Lied ohne Worte in A minor for 2 violins

- Geburtstag-Marsch for 2 violins and viola

- Romance in D minor for 2 violins and viola

- String Quartet in F (fragment)

- Gavotte und Musette (in alten Style) für Streichorchester

- 11 Walzer für Streichorchester

- Toter Winkel for string sextet

- String Quartet in D minor (fragments)

- String Quartet in C (fragment)

- String Quintet in D (fragment)

- String Septet (fragment)

- String Quartet movement (fragment)

- String Quartet (fragments)

- Untitled in D (fragment)

- String Quartet in C (fragment)

- Mirror Canon in A for string quartet (fragment)

- Fugue (arr. string quartet) (fragment)

- String Quartet #5 (fragment)

Christina Fong & Christopher Martin, violins

Heather Storeng, viola

Rangzen String Quartet

Rangzen Strings

OgreOgress Audio DVD 634479454004 69:31 96kHz/24-bit LPCM Stereo

Here's a labor of love. Arnold Schoenberg was born in 1874 to Jewish parents of modest means in Vienna. His father ran a shoe store and his mother taught piano. Young Arnold's interest in music manifested itself early on. Apparently he enjoyed listening to the dance music played in the Prater and in other public parks, and before he was even ten years old, he was imitating it in works such as the Sonnenschein-Polka and the "Alliance" Walzer. For such a young boy, these works are quite accomplished, although they give absolutely no hint of the directions in which the mature composer would go. In the three Lieder ohne Worte (one of them "idyllic"), young Schoenberg tips his hat not to the Strauss family but to Mendelssohn. The Geburtstag-Marsch and Romance come from the same period. The former is missing two of its three instrumental parts, and the latter is missing one of them, and part of a second, yet they are bravely presented here as a testament to the young composer's dogged academic progress. (The missing parts make them sound more progressive than they probably were meant to be!)

By 1895, Schoenberg had secured a position playing the cello with the so-called Polyhymnia Orchestra in Vienna. It is for this ensemble that he wrote a set of eleven waltzes – more like Schubert than Johann Strauss. The Gavotte and Musette also come from this period, although it seems that these were compositional exercises for Schoenberg, who was studying with Zemlinsky at the time. At the end of 1899, Schoenberg would compose the string sextet Verklärte Nacht, his first masterpiece. A few months before, however, he would begin another programmatic string sextet, called Toter Winkel ("Blind Spot," or more literally, "Dead Corner"). The resemblances between the fragment played here (all 1:46 of it) and its famous successor are impossible to miss.

Schoenberg's experiments with tonality took a radical turn in 1908, the year in which he completed the String Quartet #2. Prior to his first completed quartet, however, there were other attempts, and fragments from those are included here. One is as short as 17 seconds, but there also two lengthy fragments of a double fugue; in fact, Quartet #1 also ends with a double fugue.

Fragments from later works include five from an abandoned string quartet from 1926, and most tantalizingly, four from what might have turned out to be Schoenberg's String Quartet #5. These date from 1949, and appear to have been the result of a request from the Juilliard Quartet for a new work – never to be completed, of course.

About three-quarters of the length of this audio DVD is devoted to very early works that sound quite unlike Schoenberg. Most of the balance of the program consists of fragments – one as short as eight seconds long. In other words, one has to adjust one's expectations before listening to this disc. Paradoxically, the impression given by hearing so many Schoenbergian fragments back to back is less of Schoenberg and more of… John Cage? At any rate, the experience is strangely satisfying, but definitely not run-of-the-mill.

Were it not for the Arnold Schoenberg Center in Vienna, this disc would not have been possible. Of course, as much credit has to be given to the performers, who turn what could have been an academic exercise into real music-making. Somehow, they make sense of it all. The playing has a family-like intimacy, even when the ten "Rangzen Strings" are involved. The 96kHz, 24-bit recording is excellent, and there are helpful booklet notes by Severine Neff, to guide the listener through the juvenilia and the teasing fragments. OgreOgress discs are available through cdbaby.com.

Copyright © 2008, Raymond Tuttle