The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weinberg Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

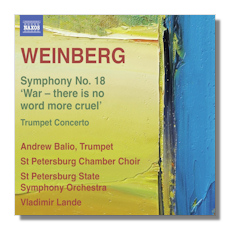

Mieczysław Weinberg

- Trumpet Concerto, Op. 94 *

- Symphony #18 "War – there is no word more cruel", Op. 138

* Andrew Balio, trumpet

Tatyana Perevyazkina, soprano

Ekaterina Shikunova, alto

Vladimir Dobrovolsky, tenor

Zahar Shikunov, baritone

St. Petersburg Chamber Choir

St. Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra/Vladimir Lande

Naxos 8.573190 70m

This Naxos series featuring the symphonies of Mieczslaw Weinberg is growing more intriguing with each new issue. Those readers who have been following it are aware of the debt to Shostakovich in Weinberg's music. But I'm coming to the point of view that Weinberg was still very much his own man, a composer who made no serious attempt to consciously imitate or absorb stylistic aspects of anyone else. In recent past reviews here at Classical Net which covered the Symphony #6 (Naxos 8.572779), Symphony #12 (Naxos 8.573085) and Symphony #19 (Naxos 8.572752), I noted the Shostakovich connection, but still found the works of significant artistic worth. In the Symphony #18, subtitled War – there is no word more cruel – Weinberg goes in a slightly different direction: the music is very dark and meditates on the horrors and sadnesses of war, while exhibiting relatively little in the writing that brings the style of Shostakovich to mind.

The Eighteenth is a choral symphony and the most profound work I've encountered thus far in the Naxos series. It is the middle panel of a trilogy, which began with the Seventeenth, which like the Nineteenth, is purely instrumental. Cast in four continuous movements, the Eighteenth begins with a long opening movement (15:31) for orchestra only. The first half is marked Adagio and is dark and meditative, featuring sparse instrumentation initially. A brief ceremonial passage for brass cannot break the gloomy character, but when the tempo eventually changes to Allegro, the mood intensifies, turning mournful and desperate while building toward a climax that is never quite fulfilled, as the music suddenly begins to fade near the end. The second movement, written to a text by Sergei Orlov, He was buried in the earth, features some beautiful, consoling choral music. But again the mood is mostly dark throughout its twelve and a half minute length. Things turn a bit brighter in the twelve minute third movement: set to a folk text entitled My dear little berry, you do not know the pain that is in my heart, the music begins with lively female voices singing an attractive, rhythmically appealing theme. Still, despite the more colorful, lively music, the feeling of sorrow and darkness remains. Midway through the music builds to a climax that once more seems not quite to resolve the tension. The brief finale (4:11) features a text by Alexander Tvardovsky entitled War – there is no word more cruel. Here, with a cappella singing throughout, the music takes on an almost medieval character in the low tones of the male singers and the mournful higher notes of the female singers, yielding a bleak but moving closing panel. It is an unsettling but masterly work.

The Trumpet Concerto is cast in three movements: Etudes, Episodes and Fanfares. The first movement is lively and begins ebulliently, with leaping scales from the trumpet. The whole movement is rhythmically quite interesting in its playfulness and sense of humor. Yes, Shostakovich is present in the music, but not so prominently. Curiously, much of the slow and dark second movement is dominated by the orchestra, the trumpet playing muted initially and only finally asserting itself in a central episode. The demure character the trumpet exhibits in the second movement is atoned for in the finale, wherein the instrument seizes the spotlight and turns confident and sassy. Here, the music opens with repeated trumpet notes that at first seem to call to mind the opening of Mahler's Fifth Symphony. But no, it becomes a partial quoting of Mendelssohn's Wedding March instead. The movement's subtitle, Fanfares, is quite appropriate, for what we hear is what seems like a series of cadenza-like fanfares, some of which recall the trumpet writing in Stravinsky's Petrouchka. In the end, this must be assessed a fine, quite witty work, if not a first-rate masterpiece.

The performances in both works are top-notch. Trumpeter Andrew Balio plays with incredible feeling and technical skills, and the orchestra in both works delivers excellent work under the masterful leadership of Vladimir Lande. The St. Petersburg Chamber Choir and the four vocal soloists sing splendidly in the symphony as well. The Naxos sound reproduction is vivid and powerful. Strongly recommended – and I anxiously await the next issue in this marvelous series.

Copyright © 2014, Robert Cummings