The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Flagello Reviews

Rosner Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Music for Symphonic Wind Ensemble

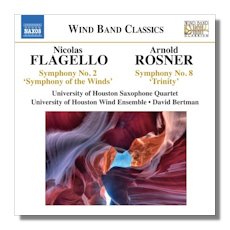

- Nicolas Flagello:

- Odyssey, Op. 74

- Valse noire, Op. 45b (transcr. Simmons)

- Symphony #2 "Symphony of the Winds", Op. 64

- Concerto Sinfonico, Op. 77b (transcr. Patterson) *

- Arnold Rosner: Symphony #8 "Trinity", Op. 84

* University of Houston Saxophone Quartet

University of Houston Wind Ensemble/David Bertman

Naxos 8.573050 74:37

Summary for the Busy Executive: Betwixt and between.

After the Second World War, neoclassicism gave way to serialism as the dominant idiom in American music. However, many American composers, across a spectrum of "difficulty," eluded classification altogether. Nicolas Flagello, for example, wrote in a neo-Romantic idiom different from people like Samuel Barber or even his own teacher, Vittorio Giannini. Arnold Rosner, about 15-20 years younger, put together an amalgam of quasi-modal composers like Hovhaness, Bloch, and even Vaughan Williams to come up with a language all his own. Both men met with resistance. New music, I have to admit, has its fashions, and neither Flagello nor Rosner latched on to any of the hot markets from the Fifties and Sixties on. I think it a bit of a disgrace that the Big Five ignore their music, especially when these organizations have invested heavily in music that has sunk without a trace since the premieres. However, Flagello and Rosner have enjoyed a bit of a Renaissance during the rise of the compact disc. Recording production, especially of chamber music, has become cheaper, smaller labels have generally been eager to claim niches in the concert repertoire, and regional American, European, and Asian orchestras have been more open (usually for lack of dough to indulge in the hot-ticket items) to provide professional readings of orchestral works that fly under the U.S. cultural establishment's weak radar.

Flagello gravitates toward the dark side of the emotional spectrum, even in smaller works. He doesn't often succeed with "bright" moods, and a troubling, anxious undercurrent usually moves beneath the surface of his so-called light music. Odyssey, written for the Cornell University wind ensemble and the legendary American bandmaster Maurice Stith, is a case in point. Flagello uses the basic building block of the half-step – usually an interval that increases tension – to erect two main themes, one descending and the other ascending. The second theme has its origins in a transitional section during the exposition of the first. After a lugubrious opening, the music angrily cuts loose on the descending idea. Then the second theme takes over, not quite as intense, but nowhere near laid-back. Along the way, the stabbing half-step becomes a whole step and turns the Angst into something less disturbed, although still powerful. Unlike producer Walter Simmons who sees any psychic relief as false hope, I hear a measure of hard-won triumph at the end. Despite its relatively short nine minutes, this piece satisfies.

This last point is by no means a given. For me, Flagello usually needs a bit of space in which to develop his ideas. The Valse noire to me shows this. Flagello wrote it as a test piece for accordion (known as Introduction and Scherzo), and producer Walter Simmons points out that it has become a repertory staple for classical accordionists – not the most numerous of musicians. Simmons, with Flagello's implicit blessing, arranged the work for saxophone quartet and retitled it. My lack of enthusiasm for the piece comes down to nit-pickery. The ideas, of extremely high quality, need more time to realize their potential. Such themes wouldn't be out of place in a symphony. Here, they strike me as stunted.

Compared to the Flagello's First Symphony, the "Symphony of the Winds" is light-er, but by no means light. Flagello's control over the architecture of the entire work impresses. He composes three movements – an opening sonata-allegro, a slow aria, and a full-blown fugue – based on the same two ideas – a rising minor third and a descending second followed by a larger downward hop. He then puts his considerable chops to work, devising variations on one or the other cell. For example, the fugal subject of the finale strings together the two basic ideas. The effect on a listener is like watching time-lapse photograph of a plant growing from seed. Beyond that, of course, Flagello aims not only to impress listeners with his craft but to move them as well.

I've reviewed the death-haunted Concerto Sinfonico before Naxos 8.559296, so I won't describe the piece itself. I think it enough to say that this was his last completed work before the effects of a degenerative illness stopped his composing altogether in his final near-decade, and its generally black mood contains more than a soupçon of anger. Originally written for the unusual combination saxophone quartet and orchestra, we hear the orchestral part arranged for the wind band by Merlin Patterson. As far as I'm concerned, he did a wonderful job in keeping both the essential colors of the music and the clarity of the voices. Of course, he did have Flagello's score to point him in the right color direction.

Rosner's Symphony #8, "Trinity," is the second of his symphonies to get a recording (the other being #5, on Naxos 8.559347), and it's the eighth in his catalogue. On the basis of these two alone, I suspect he's got six more wonderful symphonies in there. Naxos, please take note. Rosner writes that for many years, he considered band music fundamentally un-serious. He admits, however, that he hadn't really listened to the repertoire in any depth. When someone urged some specific works on him, he fortunately changed his mind and has written band pieces since. I regard this as a significant contribution, like the Flagello, to the large wind ensemble. The work has three movements: "Ave Maria," "Le Rondeau du Monsieur le Diable," and "Pythagoras." Rosner has explained something of the ideas behind the work, but because I don't understand them, I can't talk about them. In any case, the music matters to me more. The first movement reminds me of a cross between chant and a Renaissance motet, and manages to evoke the spirit of a choir in a stone cathedral. The second movement, a scherzo, seems to go even further back, to the vigor of dances of the early Renaissance. There probably haven't been so many Landini cadences in a single score since Landini. It's a virtuoso piece of orchestration as well, with a particularly arresting section for tuned percussion. The finale, difficult to categorize, sounds the closest to Hovhaness, with long-breathing chorales sounding over smaller motives in competing phrases and rhythms. I love it all.

The performances from the University of Houston winds are superior, particularly their Concerto Sinfonico. All of this music requires concentration and discipline, an ability to shape long, complex spans, and gets it in conductor David Bertman. His band knows how to both sing and dance, with wonderful tone and ensemble clarity, besides.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz