The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Tavener Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

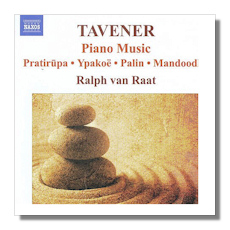

John Tavener

Piano Music

- Zodiacs

- Ypakoë

- Palin

- Mandoodles

- Pratirãpa

- In Memory of Two Cats

Ralph von Raat, piano

Naxos 8.570442 DDD 61:00

Sir John Tavener's music can seem so wispy that it is almost in danger of blowing away. Played on the black and white of a piano, though, it seems to become more corporeal. The works on this CD were composed between 1977 (Palin – not an allusion to a certain vice presidential candidate!) and 2003 (Pratirãpa, which, at almost 30 minutes, is by far the longest work on this CD).

Tavener is one of the more spiritual composers at work today. He was raised as a Presbyterian, became deeply interested in Roman Catholicism, and later joined the Russian Orthodox church. In recent decades, he has looked ever more to the East, incorporating Hindu and Sufi elements into his music, for example. As a composer, at least, Tavener's spirituality has become increasingly all-embracing. Concomitantly, his reliance on Western forms of composition has become weaker. His piano music's iconoclastic mysticism suggests another very spiritual composer: Olivier Messiaen. Messiaen's muse, even at her most Catholic, is more sensuous and complex than Tavener's, though. Even so, I keep expecting Tavener's piano music to burst out into bird-song.

Homophonic textures are common, and Tavener has a fondness for combining the piano's lower and upper registers, leaving a broad space in between. Thematic material isn't developed as much as it is restated and recombined. Pratirãpa, for example, is an alternation of rapt silences, the apparent tinkling of bells, and ecstatically swooping glissandos.

In his other scores, Tavener is hardly a grand-stander. These works for solo piano, however, are particularly intimate, even private. They would work well in a recital with piano music by Pärt, Scelsi, and Górecki. An hour of them in one sitting might be too much of a good thing, though, because the contrasts among them are not dramatic.

I understand that pianist Ralph van Raat consulted with Tavener before recording these works, and that the composer actually sat in as van Raat prepared this music for recording. His playing is strong and seems to have a decided point of view – these are not "wispy" performances by any means. It has been remarked that van Raat's timing in Ypakoë is considerably faster than that of another pianist who has recorded this work. (I have not heard her recording.) The discrepancy might be explained, though, by van Raat's use of a revised version of this work. At any rate, I assume that Tavener knows what he wants, and would have told van Raat if he wanted otherwise!

The booklet notes also are by van Raat, a pianist who has devoted much of his career to modern piano music, and who has the intellect and scholarship to back it up. Even if you haven't responded to Tavener's music in the past, you might find this recording worth your time, as I did.

Copyright © 2008, Raymond Tuttle