The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schiff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

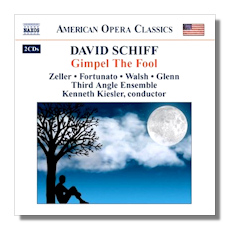

David Schiff

Gimpel the Fool

- Richard Zeller (Gimpel)

- D'Anna Fortunato (Elka)

- Kevin Walsh (Badkhen)

- Thomas Glenn (Rabbi)

- Alissa Mercurio Rowe (Fegele, Goat, Evil One)

Third Angle Ensemble/Kenneth Kiesler

Naxos 8.669010-11 96:11 2CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: Singer sung.

If I have a religion, it's either music or Anglophilia. I don't know enough Yiddish to read it. Nevertheless, the Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, according to me, has written some of the most compelling postwar literary work, especially his stories and short novellas. His output generally divides between stories set in the United States (usually New York City and its environs) and those set in the Jewish European past. I generally prefer the latter and think especially highly of his story Gimpel the Fool, a wise piece of work as well as a good one.

Gimpel, the baker of the shtetl of Frampol, is considered a fool because he believes anything people tell him. After all, why would people lie to him, a poor orphan? If today he has no faith in what people tell him, tomorrow he will lose faith in God. The town enjoys considerable entertainment at his expense. They get him to marry Elka, the town whore, who bears six children, none of them his, although she tells him that he's the father. Gimpel believes, and Gimpel loves her. However, on her deathbed, she confesses all to Gimpel, who at first refuses to credit it. She begs his forgiveness. Finally, he does both, although he still considers the children his because he loves them as a father. However, one night at the bakery, the Evil One appears to him in a dream and tells him how to exact revenge on the town for all the grief they've given him: pour a bucket of urine on the dough for the Sabbath bread. Gimpel does this, but Elka's ghost appears to tell him not to go through with it. She pays for her sins in the afterlife, as will Gimpel. Gimpel buries the tainted dough. The next day, he divides up his goods among his children, takes his prayer shawl, and leaves Frampol. He goes from town to town and comes to a kind of high moral wisdom as he anticipates joining Elka in a serene, happy afterlife.

The story attracted American composer David Schiff, who decided to make an opera on it. Most American composers have really bad luck with opera, just as they had bad luck with concert music before the heroic age of Modernism. Unlike Italy, Germany, and France, we have no operatic tradition of our own. Our musical theater consists of vaudeville, revue, and musicals, both stage and film. Our most successful operas either use the American vernacular (Gershwin's Porgy and Bess) or create something entirely new (Thomson's The Mother of Us All). Usually, our composers tap into European traditions: verismo, French grand opera, Wagnerian myth, or the European avant-garde. The results in general do not convince, although here and there you find a gem. Furthermore, opera in this country generally means the Met, an institution that turns just about everything it touches to dust or cotton candy. Its style – an insistence that it function as the company "of record" – as well as the corporate money behind it practically ensures that what you get is something safe, conventional, and not really dramatic. Someone once described the Met experience as "Four fat people bellowing incomprehensibly on-stage." I can't come up with a bon mot as neat as that, but I will say it has usually struck me as vocal freaks bellowing in pretty costumes in front of pretty sets, with all the acting ability available at a junior-high pageant.

The Met doesn't often employ real singing actors, because these don't often have the unnaturally large voices it takes to fill that airplane hangar of an auditorium. That vast space also wreaks havoc with most drama (at least subtle drama). It limits the kind of stories to blood-and-thunder "melodrammers," like Rigoletto, and to ritualistic pageants and spectacular fairy-tales, like the Ring and Turandot. Most of Rossini and Mozart don't do too well at the current Met, simply because their smaller scale and (in Mozart's case, at least) subtler psychology get swallowed up by the sheer size of the stage and scale of the sets and can't travel beyond several rows.

So an American opera composer simply means one more hopeless idealist. David Schiff, according to his own account, was compelled to compose this opera, which he began in 1975. He also supplied himself with a wonderful libretto, full of knockabout humor and great poignance, and true to Singer, to boot. The circumstances of performance (usually at temple auditoriums – in other words, not the Met) determined the scale of the work, which by no random occurrence whatsoever coincided with the scale of the story. At first, it was singers and a piano. By the final version, the instrumentation had grown to a small chamber ensemble. Schiff was so enthusiastic about the project that at one point he planned to set an all-Yiddish libretto, but thankfully he realized the impracticality, even within a Jewish community. For Schiff, the Singer story was a way to touch an important part of Jewish culture, in danger of disappearing into oblivion – a kind of Jewish Roots. I don't think he exactly longs for the good old days of poverty and pogroms, but for the art, ethical norms, and lore that flourished within that culture. He wants to understand his ancestors – his great-great-grandparents, for example – in order to gain insight into himself and his place in the world.

I must say, for me he succeeds with a weird and wonderful blend of vaudeville, musical, and classical music. This opera, among other things, entertains. The ensemble imitates a klezmer band. The singers act either very well or well enough as they go through their shtick and probably get laughs from the audience. Amateurs can negotiate some of the minor parts, but (with the exception of Badkhen, a narrator and tummler who occasionally comments on the action) the major roles need trained singers. The music and the libretto is so vivid, you can see the costumes, characters, and stage action through the CD alone. You feel for Gimpel, the poor chump, and then hate yourself for your condescension, for that condescension allies you with the people of Frampol. In short, I think a listener undergoes a moral conversion from the convention of the town to a glimpse of enlightenment – only a glimpse, because the divine beauty of Gimpel still eludes us.

After finishing the work in 1980, Schiff rescued some of the music in a purely instrumental score Divertimento from Gimpel the Fool (1982), one of the great post-war chamber pieces, which is how I first heard it (available, incidentally, on Delos 3058; however, Delos has had such trouble in recent years, you'd better grab it while you can). Nevertheless, the opera is just as wonderful. There's not a dull scene in it. The singers are ideal for the piece. The ensemble is sharp (a fiendishly close canon on the words "Mazel tov" to a klezmer riff made my jaw drop). Above all, the performance involves a listener in the drama. The CD case proclaims this as part of the "American Opera Classics" series. From the Naxos marketing department, to God's ear.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz.