The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

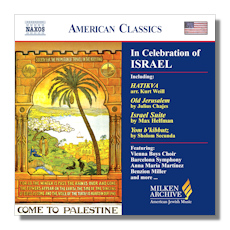

In Celebration of Israel

- Kurt Weill: Hatikva (1947) 1

- Julius Chajes:

- Old Jerusalem (1974) 2,a

- Hebrew Suite (1939, rev. 1965) 1

- Adarim (1939) 5,c

- Herbert Fromm:

- Pioneers "Halutzim" (1971) 3

- Yemenite Cycle (1961) 6,d

- Max Helfman: Israel Suite (1949) 4,b

- Walter Scharf: The Palestine Suite (1941) 1

- Sholom Secunda: Yom b'kibbutz (1952) 7

a Ana María Martínez, soprano

b Martin Schebesta, piano

c Benzion Miller, cantor

d Margaret Kohler, mezzo-soprano

1 Barcelona Symphony Orchestra/Karl Anton Rickenbacher

2 Barcelona Symphony Orchestra/Elli Jaffe

3 Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra/Samuel Adler

4 Vienna Chamber Orchestra & Boys Choir/Gerald Wirth

5 Barcelona Symphony Orchestra/Jorge Mester

6 Eastman Players/Samuel Adler

7 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra/Gerard Schwarz

Naxos 8.559461 66:00

Summary for the Busy Executive: A burst of optimism.

The years 1947-48 and the establishment of the state of Israel seemed to promise so much. It stirred Jews around the world, and not just Zionists. Indeed, some of the composers on this album – like Kurt Weill – were secular liberals, rather than Zionist Jews. Nevertheless, they all had at least one hope in common. Here at last, we thought, was the one place on earth where Jews would be safe, the always-open safe haven from the miseries and injustices of the rest of the world. As we know now, it didn't work out that way, but that was the hope. This entry in Naxos' Milken Archive series of American Jewish Music is titled "In Celebration of Israel." The works here bear testimony to the buoyancy and the dreams, rather than to the dangerous reality.

As in most collections, the items vary in quality. The Weill arrangement of Hatikva, which became the Israeli national anthem, though only two minutes long, resembles less an arrangement as such than a composition on a theme. The rhetorical form, however, is a strange one – neither overture nor quasi-sonata nor anything standard. It lies closest to a "cue" of incidental music. A strong, dramatic, narrative thread runs through it, as if the music accompanied some stage or movie action – "The Tanks Roll Forward," for example. Despite its brevity, it obviously comes from a master composer.

Julius Chajes, pianist and composer, spent two years in Palestine in the mid-Thirties. If we judge by the works here, his style didn't change all that much, deriving essentially from Ernest Bloch. However, Chajes differs from Bloch in roughly the same way as Rodrigo differs from Falla. While each has his virtues, the source works on a greater scale than does the disciple. The Chajes works come from 1939 and 1974, and I doubt whether anyone could tell which came first. Still, they are very well done, convincing on their own. You don't need the source to appreciate them for themselves. The songs – "Old Jerusalem" and "Adarim" – are beautiful, with a touch of Middle-East melismata. The Hebrew Suite comes out of Chajes's Palestine period, a combination of travelogue and, here and there, philosophic meditation.

Like Weill and Chajes, Herbert Fromm fled Europe after the Nazis came to power and finally settled in the United States. He studied with, among others, Hindemith. He doesn't sound much like Hindemith, however, except in the clarity of his best ideas. The CD shows Fromm at both his best and less than that. Pioneers, written for Arthur Fiedler in 1971, amounts to little more than a bit of propagandistic toffee. The chamber Yemenite Cycle, however, written in 1960 after Fromm's first visit to Israel, runs in a much higher gear. The music is downright elegant, with hardly a wasted note, and the variety of sound from a limited number of instruments wins my admiration. The basic material lies closer to folk sources than Fromm's wont, with Yemenite and even European Hassidic turns of phrase coming into play. The technical sophistication of Fromm's treatment mirrors a similar philosophic sophistication. One feels that Fromm tries to absorb the larger, extra-musical signific! ance of his immediate inspiration, even though the composer avoids any sort of emotional heavy-handedness.

Max Helfman, though born in Poland, came to the United States early in the century. Largely self-taught as a composer, he became involved in leftist Jewish circles, notably in the labor movement and later in "heritage" education for Jewish youth. He became far more than a musical figure for American Jews. Even I, only minimally interested in Judaism either as a religion or as a culture, felt some of his influence in the Fifties, having sung, with my fellow Sabbath-school inmates, a few of his songs. Like the British Ivor Gurney, Helfman wrote a music a bit rough around the edges – possibly due to his lack of formal study – but with a core of tremendous integrity. The Israel Suite, a collection of songs for children's chorus and two pianos (here orchestrated by Charles Davidson, a Helfman student), comes from 1949. The tunes are by others, as is the case with Copland's Old American Songs, but, like Copland, Helfman has fashioned complex, yet highly singable compositio! ns of his own. The texts run in the vein of early 20th-century Jewish Socialism – a Thirties poem about five Jewish kibbutz workers murdered by Arabs (the bad blood between Arab and Jew in Palestine predates the founding of Israel by at least twenty years), others about the beauty of the land, a finale celebrating the establishment of Israel. Of all the works on the program, I like this the best for its consistently high level of inspiration and its ability to galvanize the listener.

Walter Scharf began orchestrating on Broadway during the Thirties, most notably for Gershwin's Girl Crazy. Later, he had a nice career in Hollywood, working mainly as a musical director on such films as Hans Christian Andersen and Funny Girl. Like Herbert Stothart in Wizard of Oz, he worked primarily at providing decent underscoring, the musical tissue underpinning scenes and transitions, rather than the songs that made these movies matter. (It's always been a sore point with me that Stothart got the Oscar for the Wizard of Oz score and Arlen and Harburg got only Best Song). Scharf was a fine craftsman, but not necessarily a great artist. Inspired by the death of his grandmother, The Palestine Suite dates from the early Forties. Musically, it's fairly much what you might expect: a Forties movie score with few memorable moments, prettily orchestrated. I can't muster much enthusiasm for it myself, but I should mention that Stokowski liked it enough to conduct it.

One of the prodigiously gifted American songwriters and an icon of the Yiddish musical, Sholem Secunda studied at (what became) Juilliard and, briefly, with Ernest Bloch. He knew far more than he needed to write a musical. He also composed liturgical music, arranged for Richard Tucker's cantorial albums, and tried classical forms, including a violin concerto and a string quartet. He wanted to be known as a classical composer, but his mega-hit "Bay mir bistu sheyn" has probably put paid to those hopes. I must confess I prefer the "popular" Secunda myself. Yom b'kibbutz (a day on the kibbutz) actually combines Secunda's popular and classical leanings, since the material comes from the composer's 1952 musical Uncle Sam in Israel. The themes have a demotic energy, although the symphonic treatment is rather tame. Even more than Scharf's Palestine Suite, Secunda's little tone poem sounds like Forties movie music (the composer tried and failed to land a Hollywood gig, possib! ly because the Jewish studio heads perceived him as "too Jewish"). At any rate, the tone poem made me want to hear the musical, especially with the original cast, which included the wonderful Fyvish Finkel. Maybe a recording lurks in someone's vault.

The performances are nothing less than good, and Samuel Adler, Margaret Kohler, and the Eastman Players do a sensitive, refined job with Fromm's Yemenite Cycle. Helfman's Israel Suite takes the palm for the liveliest performance, with what sounds like genuine enthusiasm coming from the Vienna Boys' Choir and animated direction from Gerald Wirth.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz