The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Milhaud Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

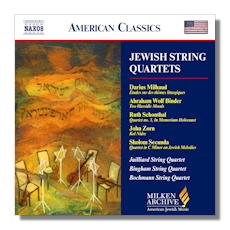

Jewish String Quartets

A Minyan of Four

- Darius Milhaud: Études sur des themes liturgiques du Comtat Venaissin (1973) 1

- Abraham Binder: Two Hassidic Moods (1934) 2

- Ruth Schonthal: String Quartet #3 "In memoriam Holocaust" (1997) 3

- John Zorn: Kol Nidre (1996) 4

- Sholem Secunda: String Quartet in C minor (1945) 2

1 Juilliard String Quartet

2 Bochmann String Quartet

3 Bingham String Quartet

4 Ilya Kaler & Perrin Yang (violins), George Taylor (viola), Steven Doane (cello)

Naxos 8.559451 77:49

Summary for the Busy Executive: Sweet and sour.

The album, a bit misleadingly titled "Jewish String Quartets," features music for that ensemble by Jewish composers either born or long resident in the United States. Naxos, as part of its Milken Archive American Jewish Music series, could have picked hundreds of composers, and the selection here represents fairly gutsy choices. The Milhaud work, for example, one of the last things he ever wrote, had not been performed since its première. That said, and despite my initial curiosity, I wish they had made room for other composers like Benjamin Lees, David Diamond, or Arnold Rosner, all masters of the genre. With CDs of this kind, you in effect buy a chance at the Lucky Dip. Sometimes you get a watch, sometimes a box of Cracker Jacks.

The Milhaud firmly belongs in the first category. The Etudes use liturgical melodies from Provençal Jewry for basic material. The Comtat Venaissin was an area in what is now the south of France to which Jews had fled after they had been kicked out of the then-kingdom of France itself. For reasons I don't know, the Church, which controlled the area, protected them. The Jews of Provence had their own liturgical traditions, going back at least a millennium – in fact, to Roman Gaul – and distinct from those of Sephardim (Jews from the Iberian peninsula) and Ashkenazim (Jews from central and eastern Europe). Commissioned to write a work on these materials, Milhaud ran up against some problems. The Provençal rite had for the most part died out by the Seventies. He had only hazy memories from seventy years before of some of the music. Fortunately, he came upon a nineteenth-century source book, which he mined for tunes. The result is a typical Milhaud concoction – long on tune, short on conventional development. Indeed, it's really a very sophisticated quodlibet in three movements, with various melodies jostling against each other simultaneously. It's as if you were in a town of the Comtat Venaissin, perhaps the market, listening to people whistling, singing, or humming what-they-will. Milhaud's contrapuntal skills and his holy horror of inflation assure that everything remains clear and buoyant. A very neat work, although a brief one.

Abraham Wolf Binder is probably best known for his work on the 1952 Union Hymnal, the one I grew up with (and which grated on my young musical sensibilities). In fact, I credit that hymnal, as much as anything else, with the fact that I haven't set foot in a synagogue for decades. Nevertheless, apparently what prevailed before was worse, but from an "ethnic," liturgical, or, God forbid, musical standpoint I can't say. At any rate, as a composer, Binder felt the influence of Bloch and indeed studied with Bloch for a time. Bloch, however, was a great composer. In all my years of listening, I've heard only one other composer who did Bloch as well as the original: Rebecca Clarke. Binder takes some Blochian tropes and gives us two "moods," a meditation and a dance – nice enough, well-written, but not much more than that. Bloch's music forces you to take a stand, for or against. It demands respect. Binder's music simply wants to be respectable.

Ruth Schonthal, born in Berlin, came, after years of flight, to the United States, where she studied with Hindemith. Apparently, she had considerable works to her credit before then and, indeed, doesn't sound much like Hindemith – more astringent and expressionist. The third quartet, subtitled "In Memoriam Holocaust," is one of her few works that deal with the subject, possibly because her family spent much of her early life escaping from it. For her, the Holocaust wasn't merely some abstract archetype of evil. She lost family, people she knew, and resisted the urge to speak until she felt she was ready and able to do justice to the victims' memory. The quartet, in two slow movements, begins grave, with rich, though not thick, chords in the lower tessitura of the strings. Gradually, the individual parts separate, first with solos for each instrument, then mainly with duets – violins, violin-cello, violin-viola, cello-viola – with the other instruments in a kind of vamp. With the greater independence of parts come greater tension and quicker note values, until the instruments gradually mix back and run down into the chordal texture. It's a highly poetic movement, although I do feel it may run a minute too long. The coda, which I feel as simple repetition of a single idea, doesn't convince me. "Lament and Prayer" follows. Schonthal lays this out on more traditional, Blochian lines, although she doesn't imitate. Again, she's more astringent than Bloch. The movement is largely a lament on the solo cello, with other instruments joining in. The material is sparse, and Schonthal's job is to squeeze as much as possible out of it. Here, she takes roughly the same chance at the end of the movement as at the end of the grave, but here it pays off – a meditation of more than ten minutes with more gesture than development, and yet it kept my interest.

John Zorn has received a good deal of attention recently, as much for his attitudes as for his music. Kol Nidre, unlike much of his work, plays things relatively straight, without parody, goofin', crossover, fusion, or general horsing around. The work begins in an intriguing way, more of an abstract on the traditional chant than the chant itself (for a more straightforward treatment, listen to the classic arrangement by Max Bruch). Zorn ruthlessly cuts out notes, reducing the traditional opening phrase, for example, to two notes. Unfortunately, not much else happens, and the work goes on far too long for its substance.

Sholem Secunda, composer of the best-known song of the Yiddish theater, "Bay mir bistu sheyn," wanted instead to be regarded as a classical composer, rather than as a songwriter. He had the training. He also worked as Richard Tucker's Kapellmeister (you should pardon the expression) for the tenor's cantorial albums. Unfortunately, based on this quartet (the only classical work of his I've heard), Secunda doesn't generate much enthusiasm as a classical composer. The quartet shows capable string writing and very little inspiration. Nothing really engages me, at any rate. I had to fight to stay awake. It's a generic quartet written in a generic style with nothing, as far as I can tell that shows an individual point of view or personality. It's a throwback to late nineteenth-century Russian non-nationalist style, without the genius of, say, Taneyev, let alone Tchaikovsky.

The performances are all quite fine, with the Juilliard standing out in the Milhaud, but whether that's them or the material is hard to say. The Bochmann does a lovely job in the Binder, sweetly lyrical, but they can't save the Secunda. The Zorn is done by a pick-up group and sounds like it. The players are nothing less than professional, but nothing more either. One misses a unity and a clarity of musical purpose. The Bingham has the hardest job with the most ambitious and the second-longest work on the program. They acquit themselves well, but they really do need more time with something this complex. I hope they stick with it.

The sound is very good. One can easily distinguish the individual strands of the Milhaud, for example.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz