The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

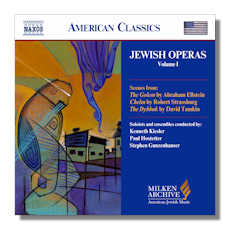

Jewish Operas

Volume I

- Abraham Ellstein: The Golem (Act II) 1

- Robert Strassburg: Chelm (Scenes 2-5) 2

- David Tamkin: The Dybbuk (excerpts) 3

1 Lauren Allardyce, soprano

1 Michael Gallant, tenor

1 Christopher Meerdink, tenor

1 Tyler Oliphant, baritone

2 Karen Longwell, soprano

2 Carla Wood, mezzo-soprano

2 Matthew Chellis, tenor

2 Richard Lalli, baritone

3 Freda Herseth, soprano

3 Joseph Evans, tenor

3 Raphael Frieder, baritone

1 University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Kiesler

2 Chamber Opera Ensemble/Paul Hostetter

3 Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra/Stephen Gunzenhauser

Naxos 8.559424 64:19

Summary for the Busy Executive: Not necessarily the Met.

By "Jewish Opera," the Naxos marketing team apparently means operas on stetl tales by Jewish composers. Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, Copland's Tender Land, Weill's Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, and Bloch's Macbeth don't count.

For most Modern composers, opera is a dodgy proposition. It takes a lot of time, a lot of notes, and there's only the slightest hope of a performance, let alone two performances. Yet, composers keep on writing. None of the operas here has held the stage. None has been recorded in its entirety. Their composition has been a series of Quixotic acts.

Abraham Ellstein, a musical all-rounder, wrote for Second-Avenue theater, commercial projects, and the concert hall. Trained at Juilliard, he also studied with Frederick Jacobi, a composer cited by Aaron Copland as one of "America's Young Men of Promise." Jacobi's music has pretty much faded from consciousness, but he took off from Ernest Bloch's "Jewish cycle" – works like Schelomo, Suite hébraïque, and so on. However, I should point out the Jacobi's music hasn't the power of Bloch's. Ellstein also works that vein, pretty much as well as Jacobi. Nevertheless, of all the works on this program, his Golem, premièred at City Opera of New York, comes off the strongest dramatically. The music portrays complex character and conflict within character. I'd love to hear the whole thing.

Robert Strassburg – a pupil of Piston, Stravinsky, and Hindemith, and author of a major study of Ernest Bloch – writes the best music on the CD. Unfortunately, best music doesn't translate into best opera. Chelm – at least the excerpts recorded here – takes almost all its musical material from a Yiddish folk song. The scoring is spare, clean, and bright as new paint. Strassburg wrote it for shoestring amateur production. Its major problem is terrible libretto. The Chelm stories, about a town of fools known as "The Wise Men of Chelm," I think one of the glories of stetl art. The Chelmians run into problems of their own making (how do you keep the birds from flying away, so you can have birdsong all the time) which they attempt to solve (unsuccessfully) by what seems a satirical application of Talmudic logic. It usually takes some visitor, with a modicum of common sense, to get them out of their own little jams. This could have been charming and ideal for the scale at which Strassburg chose to work. The badness of the libretto, however, surprises all the more when you realize that Strassburg was a decent poet, widely published. He didn't compose the libretto, but he didn't have to accept it, either. Dramatically, we get something less satisfying than a school play. The jokes creak, rather than sparkle, and the music, rather than moving things along, gives a general, vague comic wash to the stage events. There's no attempt at psychological penetration, even though at least one character, an old lady as randy as the goats she sells, could well have stood it.

Semyon Ansky's Dybbuk, one of the great plays of the Yiddish theater, has attracted all sorts of composers. Gershwin apparently considered it for his second opera around the time of his death. Leonard Bernstein, of course, composed a ballet on the subject and Shulamit Ran yet another opera. David Tamkin, who studied with Respighi, among others, worked as a composer and arranger in Hollywood. Of all the works on the CD, this gets the rawest deal. After many years of effort, Tamkin finally got a stage production with the New York City Opera. In the meantime, he had made an orchestral suite of excerpts and a so-called concert suite for Jan Peerce. The concert suite, loosely based on the plot, had other elements as well, including a hymn to the newly-formed State of Israel. What we get is a mish-mash of all three versions, with no attempt to tell a story or even part of one. This makes judging it as an opera impossible and judging it as independent music absolutely unfair. It doesn't come over musically or dramatically as much of anything, with the exception of the first scene, the only significant chunk from the original opera. Although I don't care for the musical idiom (very few people do Respighi as well as Respighi), I've got to admit the singers – Freda Herseth and Raphael Frieder especially – understand that opera is a form of theater, rather than an opportunity for vocal gymnastics.

Indeed, the performers all do well by what they've been given. In The Golem, Lauren Allardyce as the object of the creature's desire conveys sympathy, mischief, and terror. Tyler Oliphant as the golem gives us a forlorn being without family, friend, memory, past, or life of his own, doomed to carry out the commands of his creator. All the ensembles are tight and dramatic, when allowed to be. On the other hand, I wish Naxos had taken the plunge and given us one of these operas in its entirety.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz