The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Locklair Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

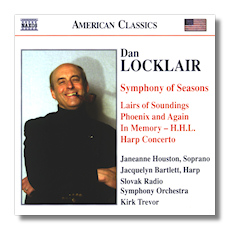

Dan Locklair

Music for Orchestra

- Symphony #1 Symphony of Seasons (2002)

- Lairs of Soundings (A Triptych for Soprano & String Orchestra) (1982)

- Phoenix and Again (An Overture for Full Orchestra) (1983)

- In Memory – H.H.L (2005)

- Concerto for Harp & Orchestra (2004)

Janeanne Houston, soprano

Jacquelyn Bartlett, harp

Slovak Radio Orchestra/Kirk Trevor

Naxos 8.559337 75:14

Summary for the Busy Executive: Gifts.

Beyond the limits of my voice, I have significant disadvantages as a singer. Although I love singing in parts, I hate performing. Church choirs, therefore, seem to me a perfect solution. The choir, usually out of sight or in back of and above the congregation (so members must awkwardly twist around to see), gives me near-perfect cover. As a result, I've also heard a lot of organ music in the wild, so to speak. In general, I've been fairly lucky in the caliber of the organists associated with "my" choirs. Unlike the dear lady parishioner who's been at the pedals for years and has trouble with anything but hymns, these organists have done the classics (Bach, Buxtehude, Franck) and explored new stuff. In this way, I first heard the music of Dan Locklair.

It intrigued me. I also liked what I had heard. I've since encountered scores I consider bland, but so far no more than three. The music is tonal, for those who care, closer to American neoclassicism than to postwar developments. Locklair studied with Ezra Laderman, Joseph Schwantner, and Samuel Adler, among others. However, his music reminds me most of early scores by Robert Ward. It's more intricate than Ward's, for sure, but I feel the same "Eastman" atmosphere – sincere, modest, psychologically uncomplicated, concerned primarily with direct communication. Eastman has produced, unfortunately, many "faceless," genteel composers, but Locklair has apparently escaped the curse.

Locklair has played the organ professionally since the age of 14, and this influences his thinking somewhat. Often, he builds his work around hymns or pre-existing popular tunes. This certainly holds true for the Symphony #1, inspired by the 18th-century poet James Thomson's long poem The Seasons, also a source for the Haydn oratorio. The symphony has four movements: "Autumn," "Winter," "Spring," "Summer." I noticed the orchestration first of all – bright, individual. Virgil Thomson once sniped at "organist orchestration" by which he meant to hit composers like Rheinberger and Franck, who think in terms of stable "registers" rather than in shifting points of color. Ironically enough, the greatest composer-organist of all, J.S. Bach, does think in terms of individual colors. Organist orchestration seems to have afflicted the nineteenth century and after. Perhaps the conflation of ever-larger instruments with the orchestra encouraged this. However, Locklair has skirted this snare, if he ever thought about it. In general, his music is bright as new paint, sharing much with the American neoclassicists between the wars.

The first movement opens with a bounding fanfare-like idea in shifting meters – to me, very similar in feel to the opening of Virgil Thomson's Cello Concerto, although rhythmically more intricate and more elaborately scored, or perhaps a Walter Piston allegro. Locklair strives to create a "jovial" mood. Unlike most symphonic first movements, it doesn't really stick to sonata form. It's really a giant A-B-A, with almost no interpenetration of its two principal ideas: the bounding theme and, in the B section, riffs on the chorale "Nun danket alle Gott." Locklair does refer to both in the brief final A section, a nice way to knit the sections together. The second movement, "Winter," is a chaconne consisting of a 12-measure chordal sequence repeated 12 times (12 months=1year – get it?). It reminds me of a junior high-school algebra word problem: "If the theme is 12 measures long and is repeated 12 times, how many measures in the movement?" But that's just Locklair having architect's fun. Like most variation forms, the chaconne game is played at two levels – the integrity of the individual variation and the cumulative narrative of all the variations. Bach's famous chaconne for solo violin probably represents this dual progression best of all. Some composers neglect one for the other. Locklair does not. He even throws in a further complication. Lines from Thomson's Seasons inspired him:

See, Winter comes, to rule the vary'd Year,

Sullen, and sad, with all his rising Train;

Vapours, and Clouds, and Storms.

Locklair creates a symmetrical dramatic structure assigning groups of variations to vapors, storms, and clouds in the following way:

Vapours Clouds Storms Clouds Vapours

None of this gets in the way of – indeed, it enhances through its dynamic arch form – the emotional effect of his music. Thus, the architecture becomes a means, rather than an end. The orchestration explores a wonderful variety of dark timbres. The psychological complexity of this movement generates great power.

The "Spring" scherzo tries to capture the brightness of the colors and sounds in mostly a swinging triple time – "mostly," because Locklair throws in a couple of 5/8 measures in as a subtle tic, now and then.

"Summer" begins soft, lush, and lazy in mainly the strings. Woodwind solos join and intertwine. Eventually, "Sumer is icumen in" joins in, and then, almost imperceptibly, "In the Good Old Summertime." The two tunes proceed simultaneously on different planes, and eventually the opening material mixes with them as well. It's a sumptuous gathering up, and even an old chestnut like "Good Old Summertime" glows. I can't say whether this symphony will endure. It has very little Angst. It goes against all sorts of strictures about serious present-day art. In a certain sense, you could even call it naïve. But, then, so is the Beethoven Sixth. If it doesn't last, it points to a lack in ourselves.

Lairs of Soundings, a song cycle for soprano and string orchestra, sets poems by Ursula Le Guin. It surprised me to learn that Le Guin wrote poems, although a title like The Left Hand of Darkness should have told me something. The first song, "Invocation" – I haven't a clue as to what it means. It fluctuates between very precise images and windy blather. It seems a "sound" poem, rather than a "sense" one and evokes mysterious forces. I have the feeling Locklair didn't know what to make of it either. The string writing is blazingly imaginative, especially in evoking non-string colors by an inventive use of registers, the vocal writing grateful. Nevertheless, this one just sort of goes by. The second movement, "Voicings," is simply a vocalise. The singer becomes another color in the string ensemble as she sings vowels. The movement opens with a string color that, I swear, sounds like an oboe. How Locklair pulls this off, I have no idea. In its way, the writing is spare. Nothing complicated happens, but every note, it seems, pierces one's core. The final movement, "Wordhoard," brings us back to Le Guin again. It's a bit Holstian, which isn't a bad thing, along the lines of the Fugal Overture. The poem is a corker, about a dragon guarding its horde. The strings bite and sting with venom. The soprano doesn't get that easy a time of it, but the setting spits sparks. The latter two movements, unfortunately, shows how far the first has missed its mark.

Wake Forest commissioned Phoenix and Again for its Sesquicentennial in 1983. Locklair's on the faculty, so it made sense to give him the gig. It turned out well. He produced an overture, based on the Wake Forest alma mater, "Dear Old Wake Forest." I must say Locklair's treatment a lot livelier than the original, which suffers from the droopy-drawers nostalgia of most alma mater hymns. The orchestra chirps as brightly as a mockingbird. The overture is in A-B-coda form, fast sections playing with fragments of the hymn sandwiching a contemplative middle that incorporates the entire hymn. The harmony of the middle impresses with its incisiveness and its impressive distance from the original.

In Memory – H.H.L is the composer's memorial for his mother. The opening phrase didn't sound promising, since it comes uncomfortably close to Barber's Adagio for Strings – the same sort of suspension, rather than an identical one. I worried that Locklair was going to write the musical equivalent of the generic pieties preachers who didn't know the deceased come up with as eulogies. But Locklair does find something of his own to say. At the very end, one hears little plucks that subtly hint at Mrs. Locklair's favorite hymn, "Jesus Loves Me." Overall, it does well by her by conjuring up someone specific.

I've always considered a harp concerto, even harp writing in general, a supreme test of composers born into the Modern era and beyond. For one thing, it can't compete with the volume of a modern orchestra, so a composer writes for fewer instruments, keeps the lid on, or does his best to fool the ear. Thousands of years old, harp technology hasn't changed as much as music itself has. After all these years, even with the addition of so-called "chromatic" pedals, it remains essentially a modal instrument. With its pedals, the harp both transposes and modulates, but it takes some very fancy footwork indeed to accomplish a straight chromatic run. Furthermore, I don't believe you can't have three adjacent half-steps in a chord. The instrument isn't suited to highly chromatic music like dodecaphony, for example. The Hindemith and Krenek harp sonatas, the Ginastera concerto for harp, and the harp writing of Britten are all tours de force. Most composers – as diverse as Debussy, Ravel, Hovhaness, Grandjany, and Salzedo – work with the harp's modal character.

So does Locklair. The concerto depends heavily on modes. The first movement (Mixolydian on G), "Dialogues (Heralding and Joyous)," begins with fanfare ideas of largely fourths and fifths, quickly taken up by the harp. It's another Pistonian allegro, with irregular striding rhythms and meters, and temporary key shifts. Locklair leaves most of this kind of heavy lifting to the orchestra, and he tends to keep the lid on in order to let the harp sound. In his notes to he work, he likens the form to a sonata, but with a difference. Contrary to usual practice, all of the key-switches occur in the exposition, rather than in the development. I read that with a huge grain of salt, but when I listened, Locklair won me over. The development is pure Mixolydian on G (G to G' on the white notes of a keyboard). However, a highly active motific argument justifies the term "development." This results in a curious feeling of suspension. The herald ideas return at the end.

The slow second movement, "Variants (Still and Gently Moving)," resembles a chaconne in conception, founded on a harmonic progression that uses chords based on each note of the 12-tone scale. So it's a tonal pun on dodecaphony. Locklair claims that the entire concerto rests on this progression, but I haven't been able to hear it. I have only one complaint: Locklair doesn't give the harpist much to do, confining the instrument largely to accompaniments and arpeggios.

"Contrasts (Very Quick and Vibrant)" is a more-or-less traditional sonata-rondo with two themes – a rhythmically vibrant A section in Lydian mode (F to F' on the white keys of a keyboard); a more relaxed, pentatonic theme – plus a relatively substantial cadenza for the soloist: A B A' B' cadenza A'. It doesn't hit me as a particularly profound work, but it is indeed attractive and closes the concerto in a convincing way.

Kirk Trevor and his Slovakians let all the color of Locklair's writing come through. They do well enough to do the composer a good deed. On the other hand, they don't reveal hidden depths. At this point, I don't know how many depths remain hidden, but I suspect a better performance could occur. However, you probably won't hear it in your lifetime, especially not from an American orchestra. It says volumes about the state of our national musical health that a Mittel-Europa orchestra performs this. I like harpist Jacquelyn Bartlett's work, but I wish the engineers had placed her more forward, and to hell with a "natural" acoustic. Soprano Janeanne Houston, however, knocks me out. She sings Le Guin's poetry as if she understands it and she gets down to the intense nub of beauty in the vocalise. This is an attractive disc.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz.