The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Modern Works

Kyle Gann

Nude Rolling Down an Escalator - Studies for Disklavier

Kyle Gann, Disklavier

New World 80633-2 DDD 61:24

Kyle Gann

Long Night

Sarah Cahill, piano

Cold Blue CB0019 DDD 25:08

Rick Cox

Fade

Rick Cox, electric guitar

Thomas Newman, piano

Peter Freeman, bass and signal processors

Cold Blue CB0020 DDD 25:05

Jim Fox

Descansos, past

Barry Newton, double bass

Erika Duke-Kirkpatrick, Jessica Catron, Aniela Perry, Rachel Arnold, cello

Cold Blue CB0021 DDD 15:07

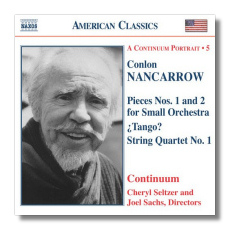

Conlon Nancarrow

- Pieces #1 & 2 for Small Orchestra

- Prelude and Blues

- Sonatina (trans. Y. Mikhashoff)

- String Quartet #1

- Study #15 (trans. Y. Mikhashoff)

- ¿Tango?

- Toccata for Violin and Player Piano

- Trio Movement

Rachel Evans, viola

Maria Kitsopoulos, cello

David Krakauer, clarinet

Celeste Marie Roy, bassoon

Joel Sachs, piano

Cheryl Seltzer, piano

Mark Steinberg, violin

Mia Wu, violin

Continuum/Joel Sachs

Naxos American Classics 8.559196 45mins

Kyle Gann is more famous for writing about music than for writing it – he is a critic for publications such as the Village Voice. Nevertheless, he is an accomplished composer, as shown by recent releases on the New World and Cold Blue labels. Gann's ten studies for Disklavier extend an idea that originated with American composer Henry Cowell and carried out by Conlon Nancarrow – that is, if some piano music worth writing is too complex (too fast, too rhythmically convoluted, too full of notes, etc.) to be played by a human pianist, then why not enlist the aid of a piano-playing machine? Before the Disklavier became available, the machine in question was the player piano, that old staple of Aunt Harriet's parlor. Now, however, much of what Cowell and Nancarrow envisioned can be more easily produced using the computer technology, and specifically, the Disklavier.

Gann's studies for Disklavier, which he has been writing since 1997, can function as humorous experiments in perception. Texarkana, the fifth in the series (and the first on this CD), initially sounds like a straightforward bit of ragtime until one realizes that the "right hand" and the "left hand" don't quite line up the way they do in Scott Joplin, for example; the Disklavier allows an infinite number of rhythmic displacements, both subtle and obvious, to be carried out. In Petty Larceny, Gann takes quotes from Beethoven's piano sonatas – most, if not all of them – and jumbles them on top of each other and back to back in a bizarrely funny collage. Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, a reference to Marcel Duchamp, exploits the Disklavier's ability to play superhuman scales and tremolos with literally superhuman sang-froid. Most of the studies are short, but the last, titled Unquiet Night, is more than 16 minutes long. In the perhaps gently sarcastic words of annotator John Luther Adams (himself a fine composer), "Seven bebop chords and six or seven tempo layers is all [Gann] needs to sustain this lovely study in ambiance." All in all, this is a fun disc, although I confess to feeling a little alienated by hearing a "pianist" who plays better than Liszt, Richter, and Cliburn combined!

Unquiet Night's predecessor and companion is a work called Long Night, inspired by the writings of philosopher Martin Heidegger. Live, it requires three pianos, not a Disklavier. However, the piece's three independent layers may be realized in the recording studio by a single pianist, with overdubbing, as there is no overt synchrony among the layers. Each layer is comprised of variably repeating loops – the pianist(s) choose the number of repetitions. Written in 1980-81, Long Night owes something to the quiet ambient music compositions of Brian Eno and others, but Gann's music never allows the listener to be lulled into complacency. As the three independent layers of music in Long Night rub up against each other, sometimes smoothly and at other times abrasively – heat and light of various intensities are produced; it is not merely pretty. The music never takes the listener quite where he or she expects it to.

Rick Cox's Fade makes a sensible follow-up to Gann's Long Night. The latter's simple piano textures are followed by Cox's more complicated ambiance of electric guitar, piano (here played by film composer Thomas Newman), bass, and signal processing. At times, the textures are relatively thin, and the identities of the instruments remain distinct, but it is Cox's obvious pleasure to combine and alter them in such as way as to suggest a single hybrid instrument. Almost halfway through the piece, the music reaches a short climax in which the bass dominates. This has the effect of bursting open the piece's apparent soundstage: suddenly, the music seems to surround the listener, where earlier it had existed within in a more closely defined space. Overall, Fade suggests the image of attenuation, and of musical substances continuously being poured from one container into another. Hard outlines are rejected in favor of more softer and more abstract boundaries between the work's horizontal sections and vertical layers.

The most immediately appealing of these three Cold Blue works is Jim Fox's Descansos, past, a requiem-like piece for double bass (always plucked) and an ensemble of four cellos (always bowed), multiplied by overdubbing into a choir of nine. The plucked bass notes would suggest jazz were it not for their hypnotic obsessiveness, like the tolling of bells. The bowed cello chords reach from the instruments' rich lower registers to their keening uppermost reaches. If Samuel Barber had been born a half century later as a forward-looking resident of the West Coast, his Adagio for Strings might have sounded a lot like Jim Fox's Descansos, past.

All three of the Cold Blue discs are artistically and attractively packaged, but with a minimum of booklet notes, as one expects from this label. The material on these three discs would have fit comfortably onto a single CD, yet I feel that it was appropriate for the label to release these works separately on three lower-priced CD singles… all the better to appreciate each on its own merits.

Speaking of Conlon Nancarrow, Naxos' continuing series of discs devoted to the New York City-based ensemble Continuum is an all-Nancarrow outing. The composer is remembered almost exclusively for his intricate compositions for player piano. He had been a mature composer for more than a decade, however, before he began to use that instrument. This disc contains music from the first decade of his career as a composer, and music from the end of his career, when he began to return to "live" instruments. The Toccata originally was written for violin and conventional piano, but the repeated piano notes made it unplayable in that form, so Nancarrow later adapted it for violin and player piano. The disc also contains a one piece that goes in the opposite direction – originally written for player piano, Study #15 works well in a transcription for piano, four hands by Ivar Mikhashoff.

Nancarrow's earlier works sound a little bit like Stravinsky and a little bit like Ives. When he started using the player piano in the 1940s, though, he spoke in a voice like no one else's, although he's had several followers since then (for example, Gann, who published a definitive book about Nancarrow in 1995). To my ears, much of his music displays the enthusiasm and freshness of childhood, even when it is the most mathematically complicated. For example Study #15 is a canon in which the same material is played at different tempos, precisely defined by the ratio 4:3. (Continuum's pianist/directors Setzer and Sachs make it sound easy.) That, however, is one of Nancarrow's simpler confections! The disc comes to a winning end with the Piece #2 for Small Orchestra, commissioned for Continuum by the goddess of new American music, Betty Freeman. Nancarrow's enthusiasm at being reunited with a real orchestra is difficult to miss in this work.

This CD was recorded in 1989 for the Musical Heritage Society, which explains, I suppose, its relatively short length. Give it a try, but don't miss the opportunity to discover some of Nancarrow's hair-raising studies for player piano.

Copyright © 2005, Raymond Tuttle