The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Torke Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

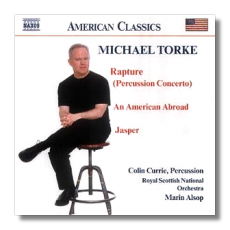

Michael Torke

- An American Abroad

- Jasper

- Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra "Rapture"

Colin Currie, percussion

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Marin Alsop

Naxos 8.559167 DDD 61:20

Summary for the Busy Executive: Three pretty bores.

I have long known that Michael Torke and I don't share ideas on what we want music to do. Early on, Torke's inspiration was painterly. Although that has abated somewhat, he still regards the fact that music must unfold in time as music's "slavishness" to time, and his goal for music is an ecstatic stasis – ignoring time, in effect. On the other hand, I would argue that music shapes time, attempts to master it through a meta-narrative (that is the movement of a story, rather than telling a story). For me, Haydn hit the nail on the head when he said that he learned to write symphonies through comic opera. It's not, as you might think, a matter of Torke's early flirtation with minimalism. The minimalist music of Reich and Adams, for example, moves like gangbusters. In Reich, the movement stretches out over a period longer than normal, but it does move, even powerfully. Reich isn't interested in stasis.

Given this fundamental difference, it would be unusual indeed if I found anything to like on this disc. Truth to tell, I did like spots, mostly in the percussion concerto, possibly because Torke's rhythms fostered the illusion of movement. An American Abroad, on the other hand, does itself no favors with its title reminiscent of Gershwin's An American in Paris. It's the difference between a nice try and a work of genius – unfortunately, not Torke's. An American Abroad goes on for a couple of minutes longer than the Gershwin, but it sounds like hours. Jasper noodles around for eleven minutes with a basic diatonic "row." The orchestration comes across as slightly more varied than that of An American, mainly because Torke has stooped (horrors!) to mild dramatic contrast. There's a Leroy Andersonian middle section that first charms and then manages to outstay its welcome. The orchestral writing is gorgeous and expert and I don't care. The music seems stuck in the middle register.

The percussion concerto interests me most of the three pieces (although still not all that much), for reasons already stated. Torke has this long liner note on his inspiration in Yeats's late poem "News for the Delphic Oracle" (not "a Delphic Oracle," mistakenly cited by Torke). As with most artists telling us civilians about the sources of their inspiration, this kind of soul-baring seems to have little to do with the work itself. Certainly, the music doesn't bring Yeats to my mind. But that, of course, is ultimately beside the point. How does the work itself come over? For me, it's a very long twenty-eight minutes. Torke talks about the nexus between repetition and ritualism. I get only the repetitive part. The composer divides the concerto into three movements: "Drums and Woods," "Mallets," and "Metals" – a nice way to discriminate the characters of percussion music. I like "Metals" best. It has more jazzy life. But, again, despite the percussion hopping about like a flea on a skillet, the orchestra remains mostly in a bland middle register. It is as if Torke has wrapped the music in warm, wet towels. From a performance and technical point of view, however, this is one outstanding disc, probably in the top ten in Naxos' American Classics series. Marin Alsop and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra play with commitment. Most of the heat comes from them, rather than from the composer. Virtuoso percussionist Colin Currie sounds like he's having a blast. I'd love to see him at work. The sound is wonderful: full and remaining clear. Praise to Naxos for committing so much to the project.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz