The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

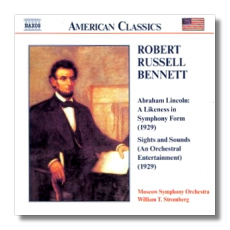

Robert Russell Bennett

Symphonic Works

- Abraham Lincoln: A Likeness in Symphony Form

- Sights and Sounds (An Orchestral Entertainment)

Moscow Symphony Orchestra/William T. Stromberg

Naxos 8.559004 53:27

Summary for the Busy Executive: Great (Irving) Caesar's ghost!

Like most Americans, I first knew of Robert Russell Bennett (1894-1981) as Broadway's premier orchestrator. The sound of Rodgers and Hammerstein, for example, is largely the sound of Robert Russell Bennett. Indeed, people prized Bennett more for his orchestration skills than for his original music. He studied with Nadia Boulanger but was canny enough to realize that symphonies and string quartets wouldn't allow him a family. Much of his concert work is slight, mainly because that's all the time he felt he could give. Nevertheless, even the light stuff shows a very fanciful mind. His Rondo Capriccioso for flute quartet (1918), for example, has the chiasmic rondo structure A-B-A-C-A-B-A, but the C section is a theme with variations. Heifetz recorded a Song Sonata and Hexapoda: 5 Studies in Jitteroptera (at least the title wins a prize). Nevertheless, Bennett also produced a few ambitious things. I have a recording of a very attractive violin concerto with fiddler Louis Kaufman and Bernard Herrmann conducting. The Abraham Lincoln symphony (1929) is probably his most ambitious work.

The symphony had a vogue. My mother's Thirties college textbook, listing the themes of 100 symphonies - including Beethoven and Brahms, but not all the Mahlers - deals with this one. It lists nothing by Piston or Diamond or Sessions. By the Forties, however, Bennett's homage to Lincoln had disappeared from serious discussions of American concert music. But all was not necessarily well beforehand. In his Memoirs of an Amnesiac, Oscar Levant relates the following:

Russell Bennett wrote a piece for symphony orchestra about Abe Lincoln at this time. When Irving Caesar [the lyricist of George Gershwin's "Swanee"] heard it, he commented that he'd come to the conclusion that John Wilkes Booth didn't kill Lincoln - Robert Russell Bennett did.

Nevertheless, the themes in my mother's textbook intrigued me. They didn't look like any other music I knew. I plunked them out on the piano keys, and they still hadn't lost my interest. Consequently, I was pretty excited at the release of this recording.

My enthusiasm dimmed a bit, however, once I actually listened to the "likeness." A Major pleasure of symphonic music lies in a feeling of inexorable transformation - following a close argument or listening to a tale well-told. Although one notices themes, connections among movements, a somewhat cyclical construction, there really is an awful lot of note-spinning and no symphonic argument to speak of. It all sounds gorgeous, and I'd lie if I didn't admit I heard some arresting moments - the beginning of the second movement, for example, which put me in mind of the opening of Virgil Thomson's (later) suite from Louisiana Story.

Yet I can't call any movement a success or Bennett's musical language all that interesting in itself. The work suffers from emotional inflation, much like the purple-poetic titles Bennett gives to each of the four movements: "His Simplicity and His Sadness," "His Affection and His Faith," "His Humor and His Weakness," and "His Greatness and His Sacrifice." The first movement wins the Worst of Four prize. Bennett begins an interesting idea and can't sustain it or gets distracted by a bright, shiny something else. It comes across as eight minutes of noodling around. Bloch's America, admittedly one of his weaker pieces, written around the same time, is certainly episodic, but beneath each episode runs a complex symphonic argument. It coheres far better and speaks more compellingly. Bennett's second movement begins beautifully, but the major contrast ("His Faith") is again filled with hot air. Lincoln's a tricky figure to write about. The artist always runs the risk of bombast and bathos - traps not even Copland managed to evade entirely in his Lincoln Portrait. Copland, however, knew enough to realize that eloquence is often achieved through spare means. For Bennett, eloquence usually means throwing in more instruments. The movement that succeeds best for me is the scherzo. It's the most coherent and focused and the least diluted with notes that merely take up time. For me, the symphony serves mainly as a lesson on the difference between the good and the third-rate. I find very little mystery in why the symphony hasn't been played for at least fifty years.

Bennett wrote Sights and Sounds about the same time as the symphony and submitted both works to a competition bankrolled by RCA Victor. Bennett won for both works, as did Copland for his Dance Symphony, Bloch for Helvetia, and Gruenberg for his symphony. Bennett aimed lower than in the symphony and achieved far more. Indeed, despite a somewhat "faceless" idiom (I doubt anybody would guess a Bennett piece in a blind test), the suite nevertheless wins with wit, charm, and (this time) genuine poetry. The success of this suite and of other Bennett works I've enjoyed suggests to me that Bennett is primarily a miniaturist, a lyric (as opposed to epic or tragic) poet of a very high order. Bennett does have a fine violin concerto, but it seems a sport, much like the piano concerto of Grieg. For Sights and Sounds, Bennett comes up with a structure similar to Mussorgsky's Pictures: movements linked by a "regular" interlude. At the end of most of the movements, a solo trumpet with a plunger mute launches into a brief commentary foreshadowing the material of the next movement and a xylophone and snare drum "count down" the number of the next movement. Just about every movement's a winner, and each portrays some aspect of life in the big city: "Union Station," "Highbrows" (full of Angst), "Lowbrows," "Electric Signs," "Night Club," "Skyscraper," and "Speed." Bennett shares some ideas among movements. The lowbrows, for example, turn up at the night club. For me, the most evocative movement was "Skyscrapers (Adagio religioso)." It's the briefest one, but it conjures up those silent newsreel aerial shots of the New York skyline in mist. The details recede into an abstract vision of great size and power.

Stromberg and the Moscow Symphony do well enough in Sight and Sounds, although the orchestra plays a bit haphazard and raw. The Lincoln likeness is pretty much of a loss, but I'm not sure anyone could save it.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz