The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Piston Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

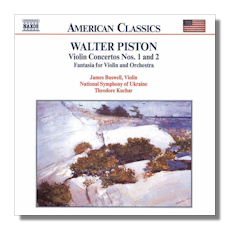

Walter Piston

Works for Violin & Orchestra

- Concerto #1 for Violin & Orchestra (1939)

- Fantasia for Violin & Orchestra (1970)

- Concerto #2 for Violin & Orchestra (1960)

James Buswell, violin

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine/Theodore Kuchar

Naxos 8.559003 60:49

Summary for the Busy Executive: Outstanding at any price. Because it's Naxos, an incredible bargain.

Against my expectation, Piston's music has always held an element of controversy, and not merely the standard one of 12-tone serialism versus tonality. Firmly tonal and no more serial than Mozart, it has nevertheless drawn the fire of other tonal composers and the praise of committed serialists and other wildebeests. Much of the argument has to do with, I think, Piston's emotional elusiveness as a composer. Even a very perceptive writer like Wilfrid Mellers gets Piston's artistic character wrong in his classic study of American music, Music in a New Found Land. Mellers and others fall back on terms like "academic" and "genteel." Piston, of course, was an outstanding academic, the author of three standard textbooks (Harmony, Orchestration, and Counterpoint). I'd be willing to bet that most composers own and consult at least one of those texts. He taught at Harvard, that bastion of the academy, for over thirty years. However, "academic" and "boring" don't mean the same thing. Many bores don't belong to the academy, and the academy has housed some very lively folks indeed.

As for "gentility," I echo Marianne Moore: "I, too, dislike it." Again, however, "genteel" and "reserved" aren't the same. In general, the aesthetic biases of Romanticism - and we've not really left Romantic notions of art and artists - work against a composer like Piston. With a decline in religion among the intelligentsia, the artist becomes the new priest: a conduit for divine truth. Such truth overwhelms, bursts out of decorous paths, like an overwhelming flood. Perhaps it's even ugly. We distrust the artist who keeps his head, his psychic balance, because the truth we seek is so potent. Gentility implies that the artist substitutes a comforting bromide for The Awful Truth. It might be, however, that the one who finds his feet in the tornado is the more powerful wizard. A poet like Sophocles - supremely sane - doesn't necessarily give you less truth than Céline. Die Meistersinger isn't necessarily a worse work than Tristan, although Parsifal might well be.

Piston's music has this sanity. At its best, it leaves the listener with the sense of a dynamo - great power under great control. Piston, a superb craftsman in an era which distrusts craftsmanship, nevertheless almost never allows craft to become the point. Craft almost always serves expression. His compositional smarts usually sharpen the expressive point, rather than merely complicate it. Piston was born in Rockland, Maine - a fact I find poetically significant as it concerns his music. His work shows indeed a New England reserve, but also the granitic strength of the Maine coast and the contemplative nature of the snow-bound New England intellectual. Once you get to know it, you can also hear its high spirits. If Ives and Ruggles tell of the hard, grand vistas of the New Englander's spiritual pilgrimage, Piston paints for me the New England landscape - only slightly less hard, more outwardly beautiful, and at times even serene, but always with a large-charge undercurrent.

Piston wrote only two vocal works. He felt he didn't really understand the medium. One story goes that when a student came to him with a little choral anthem, he walked away shouting, "No! No! Bring me anything but that!" His genius is instrumental and orchestral, which probably makes it seem to some more emotionally abstract than it really is. At its best, the word "ineffable" fits very well. With at least two of the violin works, we have him at his best. The first violin concerto comes from a period when he has hit his stride - after his search for his own voice in the Twenties and during the rush of spiritual optimism of American composers in the Thirties and Forties. The last two works come from Piston's late period - more complicated, more dark. All are well-written for the violin, and all show superb structural thinking.

I might as well deal with the last work, the Fantasia, first, since it's my least favorite. If I had my way, Piston would have continued in his Forties manner until he died. But no real artist can stand still, if only because writing the same sort of piece again and again eventually palls on a mind of real quality. Even Bach changes, even Bruckner, despite the completeness of artistic realization each may have already achieved. Piston's music becomes less quartally-based and more chromatic, which translates into emotional shadows. The one-movement work exhibits an unusual structure - a slow, meditative frame surrounding three large sections, fast-slow-fast. The frame turns the entire work into slow-fast-slow-fast-slow - an arch, where we expect the emotional weight in the central slow movement (and that's what we get). Piston wrote the work for Salvatore Accardo, a violinist known for his fast fingers, his in-tune double- and triple-stopping, and his performance of the Paganini études. The soloist gets plenty of chances to call on technique, but the piece doesn't really highlight virtuosity. It's a complex narrative, and the violinist must be able to follow the thread. That doesn't happen here, and I can't tell whether that's the performers' or the composer's fault. The work seems "cramp'd and crabb'd," arthritic as opposed to the sense of bounding freedom in the two concerti - as if Piston simply couldn't get the ideas to flow. However, I've heard only this one performance and admit the possibility that another could change my mind about the work. On the other hand, I've heard Buswell and Kuchar triumph in even more complex music, so I hesitate to lay the blame at their feet.

No misgivings at all about the first violin concerto - to my mind, one of the best of its century. Howard Pollack, Piston's biographer, asserts that Piston modeled the work on the Tchaikovsky violin concerto, something that hadn't occurred to me in all the thirty years I've known the work but, once pointed out, something that seems dead on. It's a bit like seeing the face of the girlfriend you just split up with on other women. Piston doesn't simply reproduce the character of each movement; after all, such a general scheme fits many other concerti. The resemblances come down to rather specific elements - most notably, the glorious, blazing restatement of the main theme and the violin passage work at the end of the first movement. The concerto is heroic and fun at the same time, just like the Tchaikovsky. It deserves a bigger audience.

The second concerto is a product of Piston's final compositional phase. The big-hearted innocence of the first concerto has been tempered by experience and reflection. Emotionally, it's more knowing and more mature - Humphrey Bogart rather than Errol Flynn - and less immediately winning. However, it does deliver its matter clearly and without stumbling, and Piston builds a narrative that moves. The issue of clarity is, I believe, important, because saying what one means is generally the hardest thing to do. Profundity is less clear-cut. One can claim profundity and then argue about it, but, by its very nature, one can't claim clarity with the possibility of disagreement. Generally, Piston works the drama inherent in the contrasts of classical forms like sonata-allegro. However, the contrasts spring not so much from key as from rhythm. Nevertheless, Piston scores on the important point that the various ideas do indeed contrast. The most compelling movement to me is the slow second movement. Many writers, including Pollack and Jim Svejda, have related Piston's lyricism to his Italian ancestors (the family name was originally Pistone), but I find very little similarity among Piston, Verdi, and Puccini. Rather than putting all the emotion out there, Piston holds something back - much as Hindemith does in his slow movements - and thus draws the listener in. The finale hearkens back to other Piston endings, notably that of the second symphony - foot-stomping exuberance emphasizing the tonic pitch.

Buswell plays as though he enjoys it. Kuchar and the Ukrainians not only keep things moving, but now and then get the music to dance. Sound is fine.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz