The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

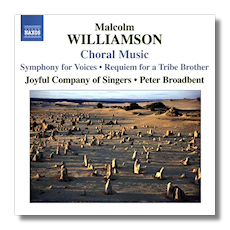

Malcolm Williamson

Choral Music

- Symphony for Voices *

- Love, the Sentinel

- Choral Suite "English Eccentrics"

- Requiem for a Tribe Brother

* Kathryn Cook, alto

Joyful Company of Singers/Peter Broadbent

Naxos 8.557783 69:42

Summary for the Busy Executive: Nice colonial boy.

The Anglo-Australian composer Malcolm Williamson (1931-2003) studied with Eugene Goossens in Sydney and then with Elizabeth Lutyens, among others, in England. He enjoyed a rising reputation in Britain from his initial Big Splash in the Fifties to roughly the middle Seventies. Then performing organization seemed to lose interest, although he kept writing and even became a Master of the Queen's Music. And Williamson resented it, becoming especially petulant over the subsequent attention paid to Britten and Tippett, although by that time he had produced no score of comparable stature to Britten's Death in Venice or Tippett's Third Symphony.

Williamson at his best wrote vigorous, attractive, and extremely well-made music. At times, the "well-made" seemed to be the point. Many's the time when I can only admire him, and I've never encountered a work I could identify as his, simply by listening. In many ways, he's a musical magpie, taking from Stravinsky, Messiaen, Poulenc, and so on. One seldom gets as good as one's sources without transforming them in some personal way.

The Symphony for Voices (1962), probably Williamson's best-known choral work, sets some complex poetry by the Australian James McAuley. Despite the title, the work is no symphony, but a five-movement choral meditation on the tangled relationship between the poet and his native country. Simply as a setting of poetry, Williamson's score represents quite an achievement. His music unsnarls the tangles of the text. Largely homophonic, it nevertheless keeps one's interest, with bits reminiscent of Messiaen's Cinq Rechants and choral music by Poulenc and the American William Schuman. Spare, even austere (I kept thinking of the harsh Australian desert), the work includes a movement entirely for a solo mezzo, and it holds together. Williamson spends considerable art on knowing when to change ideas and textures.

A decade later, during a strike in Britain, an electrical worker was killed, run over on the picket line by a strikebreaker. Williamson responded with Love, the Sentinel, a gorgeous setting of a chunk from Tennyson's In Memoriam (sections CXXVI-VII and CXXX). Again, it's a terrific bit of craft as well – an eight-minute continuous setting. Williamson keeps a tight rein on musical coherence. This isn't a "one thing after another" setting, but a tight argument. The idiom has become warmer, more obviously heart-felt since the Symphony, and all for the better. This is the kind of music you'd want at your own funeral.

The English Eccentrics Choral Suite, based on the work by Edith Sitwell, shows off Williamson's considerable wit. The suite comes from Williamson's opera of the same name. The suite consists of five movements: "Goose-weather," "An Amateur of Fashion," "From 'Sarah Whitehead'," "The Quacks," "A Traveller," and "The Old Beau." Ironically, it sounds a lot like Britten, particularly the 5 Flower Songs and the Choral Dances from Gloriana. My two favorite movements stand at opposite emotional poles. "An Amateur of Fashion" is an hilarious choral fox-trot, while "The Old Beau" (about Beau Brummel's last days) sings tenderly and compassionately over the poor lion's hard times.

Requiem for a Tribe Brother comes from 1992. Williamson wrote about the death of an aborigine he knew personally, and he responded with the most personal work on the program. The present performers sang it at Williamson's own funeral. It's an odd, unsettling mix. Messiaen rubs elbows with the English church choral tradition and pop. Lewis Mitchell points out in the liner notes at least one bit of Australian symbolism – the occasional drone of the didgeridoo in the lower men's voices. As you might expect, the work is all over the place in its effect, as well as in its sources. It doesn't add up to anything coherent. Yet, sections of it command your attention.

Williamson's works here all demand a crack choir, and Broadbent's Joyful Company of Singers certainly qualifies. They give purposeful, strong readings. If the Requiem, for example, becomes flaccid, it's not the singers' fault. The sound is clean, rhythm is sharp, intonation spot-on. The one thing they could improve upon is their diction. In the McCauley and Sitwell, they sound as if they had a mouthful of hot mushy peas. The one place where their diction becomes consistently clear is in the Requiem, precisely where least needed.

Naxos provides texts only for the Requiem, perhaps because of a kerfuffle over copyright, although I can't imagine Tennyson in copyright. Nevertheless, if you know the liturgy, the text is superfluous, no matter how good the diction. The company could have saved some ink and paper or at least given us the Tennyson. The lack of text is particularly inimical to hearing English Eccentrics. I can't make out one word in ten, even with earphones. Other than that, a fine disc.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz