The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Berkeley Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

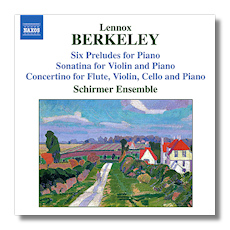

Lennox Berkeley

Chamber Music

- Sonatina for Violin & Piano, Op. 17

- 5 Short Pieces for Piano, Op. 4

- Andantino for Cello & Piano, Op. 21/2a

- 3 Pieces for Clarinet Solo (1939)

- Mazurka for Piano, Op. 101b

- Duo for Cello & Piano, Op. 81/1

- 6 Preludes for Piano, Op. 23

- Concertino for Flute, Violin, Cello & Piano, Op. 49

Schirmer Ensemble

Naxos 8.557324 61:36

Summary for the Busy Executive: Aristocratic passion.

Ten years older than Britten, Lennox Berkeley was, along with Constant Lambert, one of the few British composers of the twentieth century to fall under the influence of post-World War I Stravinsky. He even studied with the prime pedagogical disseminator of neoclassicism, Nadia Boulanger. He first made his mark in the Thirties and Forties with some very Stravinskian orchestral pieces, which still today count among his most popular. A tender artistic conscience, he withdrew many large works, which after his death have fortunately come to light both for publication and performance. He also became a friend of Britten's, and the two collaborated on a few scores, most notably Mont Juic, written as homage to the anti-Franco forces of the Spanish Civil War. Berkeley tends to get pigeon-holed as a Boulangeriste, and his craft and concern for textural clarity in his music bears eloquent witness to his training. However, outside of some early works, beneath this façl;ade lie unexpected emotional depths, not particularly neoclassically proportionate.

The Five Short Pieces for piano, terrific miniatures written in 1936, come closest to Berkeley's image among many of those listeners who know his work at all. They're all very finely worked and very French, with Ravel, Fauré, and perhaps Poulenc in the background.

The 1939 Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo, on the other hand, may have a neoclassical, Les Six bent, but in the central slow movement, one also hears Romantic meditation. All the movements, incidentally, are based on the arpeggio. This work disappeared for a number of years and in the Eighties resurfaced, dedicated to the great British clarinetist Thea King (14 years old when Berkeley composed the piece, so probably not written for her then).

The violin sonatina from 1943, like the one by Dvořák, packs a punch that belies its length. The French influences have receded, although they make themselves felt in the superb transparency of the piece. Nevertheless, one notices an expressionist element in the sonatina's psychological layers, similar to early Britten in such works as the Bridge variations, Les Illuminations, Sinfonia da Requiem, and Peter Grimes, written around the same time. The first movement sings a song "full of trouble," but clearly. It's a straightforward mini-sonata movement which offers the listener no difficulty in distinguishing the two main ideas. One can say much the same of the slow second movement, in song form. The finale comprises a set of five variations (theme, decorated theme, fantastic capriccio, recitative, waltz, and slow), with the recapitulation of the theme at the end.

In 1945, Walter Hussey, who also commissioned Britten's Rejoice in the Lamb and Bernstein's Chichester Psalms, asked Berkeley for a work and got one of the composer's best, the Festival Anthem (available on Naxos 8.557277; see my review). Ten years later, Berkeley arranged the second movement, originally a soprano solo, for cello and piano. It's a rare melody that works for both voice and instrument, simply because the voice can get much of its expression from words. The composer, even subconsciously, takes this into account. Schubert's melody for "Der Tod und das Mädchen" given straight to an instrument loses at least two-thirds of its effectiveness – probably one reason why he arranged it so heavily when he incorporated it into his string quartet. I prefer Berkeley's original, which took for its text a stanza from George Herbert's "The Flower." I miss the interaction of music and words.

The Six Preludes, also from 1945, represent a considerable advance in artistic maturity from the Five Short Pieces of a decade before. Again, none of the preludes run especially long, but the range of expression has widened. Berkeley writes with greater resource for the piano (even with some of the same ideas as Five Short Pieces), perhaps the result of keeping the first pianist, Colin Horsley, in mind. Only the penultimate movement reverts to Les Six hi-jinx. My favorite prelude is the fourth, marked "Allegretto," a salon waltz with the poise of Ravel's Pavane.

Berkeley's career peaked in the Forties and Fifties, as he wrote some of his finest scores – one highpoint, the Concertino for Flute, Violin, Cello, and Piano (or, in my preferred, Brandenburgian version, recorder and harpsichord substituting for flute and piano). Again, we feel the tug of the two poles of Berkeley's music: the extrovert, neoclassical, highly contrapuntal outer movements, with Berkeley's apparent determination to extract as many different combinations from his ensemble as possible; the reflective, slightly dark inner movements – the "arias" for flute and cello and for violin and piano. In all cases, the power is both contained and concentrated. None of the score's four movements lasts all that long, and yet you get a richness of thought and invention.

The Duo for Cello and Piano (1971), muscular and darkly Romantic, would not have found itself out of place as a movement in a major cello sonata. Berkeley's neoclassicism is highly sublimated here. Again, the music seems tinged with expressionism, though it's not as emotionally messy as most expressionist works. However, it conjures up gray skies and brooding clouds. The Mazurka, on the other hand, one of the composer's last works, tells us that he never lost his Gallic loves. The BBC commissioned the work for a Haydn anniversary, and the little piece, about a minute long, brings to mind Ravel's Menuet sur le nom d'Haydn, only in this case the object of the tombeau seems as much Chopin as Haydn.

The Australian Schirmer Ensemble does a fine job. Pianist Len Vorster stands out as both soloist and chamber-music partner. He grasps the subtleties of Berkeley's idiom, although he's less dramatic than Berkeley champion Colin Horsley. Deborah de Graaff cogently shapes the solo clarinet pieces. David Berlin's big-toned cello brings grandeur to the Duo. Elizabeth Sellars on violin would have earned my enthusiastic recommendation but for one note – the very last one of the Sonatina, gratingly out of tune. I can't believe nobody heard it. Other than that, a lovely disc of finely-wrought music.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz