The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Sibelius Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

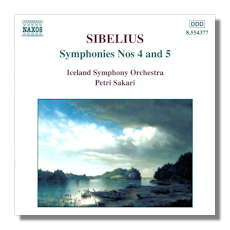

Jean Sibelius

Symphonies #4 & 5

- Symphony #4 in A minor, Op. 63 (1911)

- Symphony #5 in E Flat Major, Op. 82 (1919)

Iceland Symphony Orchestra/Petri Sakari

Naxos 8.554377 DDD 69:19

Naxos' Sibelius cycle makes impressive progress with this new release. The Finnish conductor hasn't made a false move yet, and here, his cogent direction places him in the same rank as great Sibelians such as Karajan and Maazel.

In the Fourth Symphony, Sakari's unusually slow tempos challenge the listener without losing his interest. The total timing is 37:47; compare this with commercial recordings by Maazel/VPO (32:31), Saraste (34:28), and Barbirolli (36:17). Only the third movement is distended by Sakari's frosty treatment. The tempos for the Fifth Symphony are more conventional; Sakari takes 31:17, compared to 27:15, 32:25, and 33:15, in the same sequence given above. Sakari, no doubt assisted by the Icelandic engineers and the acoustics in the Reykjavík Concert Hall, uncovers details that are not apparent in more expensive recordings featuring big-name conductors. The Icelandic double basses are particularly noticeable, and this adds needed foundation to Sibelius's sound. The conductor's lively phrasing makes even these familiar scores sound fresh.

The Iceland Symphony Orchestra, while it doesn't have the richness of the Berlin or Vienna Philharmonics, plays idiomatically. Just as important, it has a sound of its own. Internationalism, while it has its benefits, tends to minimize the factors that made orchestras sound different from each other even forty years ago. There used to be a Boston sound, a Chicago sound, a Concertgebouw sound, and so on. This is much less true today, and that is unfortunate. Although the Icelandic musicians don't always play with the most beautiful tone, tonal idiosyncrasies can make familiar music come alive, as long as they are not too jarring. I am willing to trade sculptured perfection for insights, and I think Naxos has done an excellent job matching repertoire with performers.

At this price, the only other strong competitor in these works is Maazel in his first recording, which is 35 years old and not nearly so well recorded. You won't be disappointed with Sakari.

Copyright © 2000, Raymond Tuttle