The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

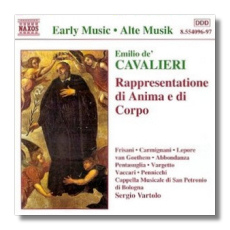

Emilio de' Cavalieri

Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo

- Anima - Rosita Frisani, soprano

- Corpo/Piacere - Alessandro Carmignani, tenor

- Tempo/Mondo - Carlo Lepore, bass

- Inteletto - Michel van Goethem, counter-tenor

- Consiglio - Roberto Abbondanza, baritone

- Compagno I - Giovanni Pentasuglia, tenor

- Compagno II - Marcello Vargetto, bass

- Angelo Custode - Patrizia Vaccari, soprano

- Vita Mondana - Marinella Pennicchi, soprano

- Avveduto - Tomasso Todesca, speaker

- Prudenzio - Maurizio Rippa, speaker

Trebles of the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra/Jiří Chvala

Cappella Musicale di San Petronia, Bologna/Sergio Vartolo

Naxos 8.554096/97 (2CDs), recorded August, 1996

The changes in musical style that were taking place in Italy in the late 16th century came to a head in 1600, with the performance and publication of three path-breaking works: two settings of Rinuccini's libretto for Euridice by Giulio Caccini and Jacopo Peri, and Cavalieri's Rappresentatione. All three composers were associated with the Medici court in Florence, and they were bitter rivals in their claims to the "marvelous invention" of drammi posti in musica per recitar cantando, dramas in music in recitative style. Emilio de' Cavalieri (c1550-1602), a Roman nobleman who had been appointed superintendent of Lorenzo I's musical establishment, had lost ground in Florence to the other two and the Rappresentatione was first produced in Rome, probably as a challenge to the others, and its innovative nature was immediately recognized and warmly received.

The production took place in the Oratory of St. Philip Neri of Santa María in Vallicella, the location of the congregation of the Oratory with which Cavalieri was associated, and it is generally considered to be the first oratorio in musical history. The body of the work is lightly scored and is mostly sung in dramatic monody; it includes speech-like recitative, madrigals, songs in dance meters, and strophic songs, with considerable reliance on the moralizing chorus in all of these forms. The libretto, by the Oratorian Father Agostini Monni, is drawn from the text of a laude dialogue between Soul and Body, and unlike later oratorios, is allegorical rather than Biblical in origin and nature. After a lengthy spoken dialogue between Avveduto (Awareness) and Prudenzio (Prudence), the protagonists, Corpo (Body) and Anima (Soul), are involved with the other characters in a variety of scenes – some contemplative, some dramatic (including some splendid effects set in Hell) – that lead to the didactic affirmation that the eternal kingdom belongs to those who serve God.

The Oratorians were committed to simplicity and naturalness, as opposed to the artificial and intellectual concerns of the Jesuits, and this is reflected in Cavalieri's music. It flows easily and melodically, without great variety or harmonic complexity, and without the vivid and florid exhibitionism that came with Monteverdi and the later Baroque composers. The singers in this performance are all competent and of no great distinction except for tenor Giovanni Pentasuglia and baritone Roberto Abbondanza, who are impressive in their roles. The small orchestra of period instruments is crisply led by Sergio Vartolo, and the musicians are excellent. There isn't much excitement in this work, but its simplicity and devotional effectiveness make it interesting and engaging, There are three other recordings, from Stradivarius, Nuovo Era, and Koch. I haven't heard the first two; the Koch release (KIC 7363), with mezzo Judith Nelson and Warren Stewart leading The Whole Noyse, is smooth and pleasant, but it is typically British in its imperturbability and not as idiomatic or as effective as this one.

Copyright © 1998, Alexander J. Morin