The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

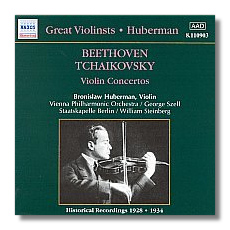

Vintage Huberman

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto*

Bronislaw Huberman, violin

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/George Szell

* Staatskapelle Dresden/William Steinberg

Naxos 8.110903 AAD monaural 67:02

These recordings are available on other CDs that cost more than twice as much. There is no reason to prefer the more expensive issues; Naxos' transfers, effected by David Lennick (Beethoven) and Mark Obert-Thorn (Tchaikovsky) are excellent. Of course, allowances need to be made for the vintage of the sound – 1934 and 1928, respectively – but modern-minded collectors who are primarily concerned about sonics will not want these monaural recordings anyway.

Huberman recorded relatively little, so every example of his playing is welcome. He was an expressive violinist, and one who could move between aristocratic purity and earthy abandon as the interpretation and music required. He was supposed to have been a difficult collaborator, but the playing on this disc is effortless. At times he was free-wheeling, and there are moments on this disc where today's violinists or producers probably would have asked for a retake. Both of these recordings are classics, however, and a few minor imperfections (more fingerprints than faults, really) don't make a lot of difference in the larger scope of these recordings. The Beethoven is noble and intimate, and Szell's conducting really stands out. There's even some good-humor in the first movement, a quality that one associates with neither this concerto nor with the unusually dour Szell. The finale breathes geniality. Actually, the entire recording is characterized by friendly music-making, an achievement worth noting, because this is a concerto that can sound frosty when well-meaning violinists play it with too much detachment. The Tchaikovsky features William Steinberg in his first outing on records; later, he would become famous for his work with the Boston and Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestras. In this concerto, Huberman digs in, emphasizing singing tone in the first two movements and gypsy passions in the finale (which, unfortunately, is drastically cut, as was the custom of the time). Although this concerto does not lack remarkable recordings, it is good to have Huberman's version back again.

Copyright © 2000, Raymond Tuttle