The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Wagner Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

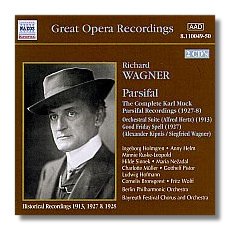

Richard Wagner

Parsifal

Historical Recordings from 1913, 1927 & 1928

Singers include Gotthelf Pistor, Ludwig Hofmann, Cornelius Bronsgeest, Fritz Wolff & Alexander Kipnis

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Alfred Hertz

Berlin State Opera Orchestra & Chorus/Karl Muck

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra & Chorus/Siegfried Wagner

Naxos Historical 8.110049-50 ADD monaural 2CDs 78:34, 79:16

Naxos' latest project is Naxos Historical – recordings whose artistic value and historic interest far outweigh the limitations intrinsic in the original materials. In the present case, these "original materials" are venerable 78rpm shellac discs. The other Naxos Historical issues released thus far – Rachmaninoff playing Rachmaninoff, vintage recordings of Elgar concertos – also were originally released on 78rpm discs.

By engaging Mark Obert-Thorn as producer and "Audio Restoration Engineer," Naxos has scored a coup, because few individuals know more about getting music out of 78rpms and bringing it to the CD-buying public than Obert-Thorn. In spite of this set's high affordability – as always, a Naxos trademark – there is no evidence of cost-cutting anywhere. Listeners can expect a first-class product: grand old recordings, better transfers and digital remastering than ever before, and informative annotations.

Alfred Hertz conducts Berlin Philharmonic in the 1913 recordings. These were acoustic in origin – no microphones yet! – and so the Orchestra (rather, a reduced ensemble of 30-some musicians, crowded into a studio) played into a single horn. This is a 37-minute "orchestral suite" from Wagner's nearly sacred opera, including the Prélude, the Transformation Scenes from Acts I and III, and the Good Friday Spell. Hertz (1872-1942) was one of the era's pre-eminent conductors of Parsifal. He was ten years old when the opera was premièred in Bayreuth, and he was the first conductor to conduct the score outside of Bayreuth, including at the Metropolitan Opera (which incidentally got him in trouble with the Wagner estate). It almost goes without saying, then, that he understood this music deeply, and that he was a qualified and capable conductor. The recording requires some tolerance, but it is amazing how much one can hear.

Karl Muck (1859-1940) spent part of the 1910s as chief conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but he returned to Germany at the end of World War One. In 1927, Columbia came to Bayreuth to record extensive excerpts from Parsifal, and Muck was the label's first choice. They could not afford many singers, however, so the excerpts that were recorded (including the Grail and Flower Maidens Scenes) went without. Bass Alexander Kipnis (Gurnemanz) and Fritz Wolff (Parsifal) were engaged for the Good Friday Spell, but Muck angrily backed down from conducting this scene when he was told that it would have to be split across three sides. Wagner's son Siegfried stepped in to record this music. Again, the value of these recordings is almost self-evident. This is the first living document of music from Bayreuth, that Wagnerian mecca, and it is instructive to hear tempos and other traditions so little separated from the opera's 1882 première. Particularly interesting are the Bayreuth bells, which were designed and manufactured for the work's première. They make a thrilling sound, something like a herd of Bösendorfer pianos, even given the engineering's limitations. (Disappointingly, they were melted down for use by the German military during World War Two.) Kipnis and Wolff are imposing and eloquent soloists. At times, there are some rough edges to these performances, probably because Muck's fees (over and above what Columbia was paying Bayreuth's management) were prohibitively high. Nevertheless, this is about as authoritative as Wagner on record gets, and the sound coming out of the shellac grooves is remarkably vivid.

Muck subsequently recorded the opera's Prélude and a large portion of Act III in the following year, this time for HMV, and at the Berlin State Opera instead of at Bayreuth. HMV brought the Bayreuth bells along, however, and they also brought two singers who had sung in performances of Parsifal with Muck at Bayreuth two months earlier: Gotthelf Pistor (Parsifal) and Ludwig Hofmann (Gurnemanz). Here, the Amfortas is Cornelius Bronsgeest. The sound is even better here, and Muck remains at his post throughout the entire recording, even for the Good Friday Spell, which again was split over several sides! Beautiful, intelligent singing abounds, and the quality of the orchestral playing is higher than it was in Bayreuth.

Perhaps understandably, Naxos doesn't provide any texts and translations, but they do offer a thorough track-by-track synopsis of what's going on. For this and for sonic reasons, this set is not recommended to listeners who are coming to the opera for the first time; they should purchase a complete modern recording and spend some time getting to know the music first. However, for those who have gained some familiarity with the score, and who are interested in hearing Parsifal as close to how Wagner envisioned it as possible, this is an essential acquisition.

Copyright © 2000, Raymond Tuttle